Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Other possible titles: Honorable Blood, Kanto and the Sailor Ogawa, The Shipwreck of Kanto and the Sailor Ogawa, Special Service Ship Kanto and the Sailor Ogawa

| Production Company | Kokkatsu |

| Scenarist | Unknown |

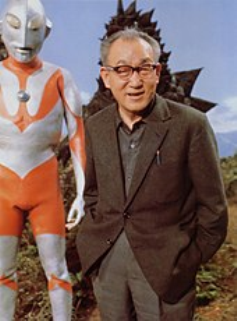

| Cinematographer | Tsuburaya Eiji |

| Chief Assistant Director | Igayama Masamitsu1 |

| Performers | Mizushima Kinzaburo (Old Chief Physician Shimizu); Nishizawa Takeo (Sailor Ogawa); Suzuki Hamako (Mother Okuni); Honda Utako (Younger Sister Oharu); Mizushima Michitarō [as Mizushima Michio] (Young Boy)2 |

| Status | Lost, except for a very brief fragment stored at Kobe Planet Film Archive and available online here. |

| Photography | Black and white |

| English subtitles | None |

| Original Release Date | January 30, 1925 |

| Length of Fragment | 3.5 minutes (length of original work estimated to be approximately 30 minutes) |

Note: I’m currently working on a review of Uchida’s very, very long five-part work, Miyamoto Musashi (1961-1965), which will take some time. In the meantime, I’m providing a “review” of a clip that has surfaced on the Internet, which has been identified by researchers as a surviving excerpt of a very early Uchida film.

As an obsessive about all things Uchida-related, I was thrilled to discover, about a year or so ago, the existence of a mysterious three-and-a-half-minute clip, the 1925 Kanto shipwreck film fragment, part of a film inspired by an actual shipwreck off the coast of Fukui Prefecture in late 1924, which has been attributed not only to the very young Uchida as director, but to Eiji Tsubaraya – the future special-effects wizard of Godzilla fame – as cinematographer.3

The historical genesis of this movie – which, except for the clip at the Kobe archive, is missing and presumed lost – is fascinating. (The details can be found in a Yahoo article available here, and on Kobe Planet Film Archive’s webpage here.) On December 12, 2024 (coincidentally, Ozu Yasujirō’s twenty-first birthday), near the village of Kōno, now part of the town of Minamiechizen, a ship called the Kanto, a former “special service ship” – the term for a Navy armed merchant vessel with concealed weaponry, also known as a Q Ship – drifted off-course in a storm, went aground on a reef and sunk near the coast. The villagers then banded together to rescue the fifty surviving sailors on the doomed ship. For those sailors who made it to shore alive, the women of the village literally used the warmth of their bodies to keep them from freezing to death. (These were known as the hitohada, or “body warmth,” rescuers.) In addition, a third-class sailor named Ogawa Sanosuke, who was on vacation in Kōno Village at the time, also participated in the rescue, bravely saving from the water the corpses of some of the 97 men who had already perished.

Not one but two film companies thought this event worthy of being dramatized on film. One of these was Japan’s oldest surviving major film studio, Nikkatsu (founded in 1912), for which Uchida, beginning in 1927, would work for most of his prewar career. The other was a tiny studio, not long for this world, named Kokkatsu (sometimes spelled Kokukatsu). However, according to film researcher Jun’ichi Suzuki, it’s unlikely that Nikkatsu produced the film of which the surviving clip is a fragment, because the cast list that survives for that film doesn’t match the actors who appear in the footage.

On the other hand, a photo, published in the March 1925 issue of a magazine called “Ongaku to Eiga” (“Music and Film”), show actors in costumes very similar to those of the performers who appear in the clip, and this photo identifies the film as “Kanto and the Sailor Ogawa,” produced by Kokkatsu. In the same issue, there’s also an advertisement for a film called “The Shipwreck of Kanto and the Sailor Ogawa,” for which Uchida Tomu is credited as director and “Tatani Eiichi” [sic] (presumably Tsuburaya, whose real given name was Eiichi) is credited as cinematographer.

In addition, on the Internet Movie Database, as well as on my own Uchida filmography on this site, an early 1925 film attributed to Uchida, titled Giketsu (Righteous Blood [or Honorable Blood]), is listed as directed by Uchida and photographed by Tsuburaya. This title of course differs significantly from the two titles cited in “Ongaku to Eiga,” and also the one listed in a reference source, published in 2008, called The Complete Catalogue of Japanese Feature Films, which gives the Kokkatsu film title as “Special Service Ship Kanto and the Sailor Ogawa.” But the cast list on the IMDb page for Giketsu shows at least some cast members who are also listed in the advertisement in “Ongaku to Eiga,” so it’s reasonable to infer that Giketsu and the film to which the Yahoo article refers (by several different names) are one and the same.

Two final details should be noted: one of the child actors who appears in the clip has been identified as Mizushima Michio, the same performer who plays the little boy in Uchida’s 1925 film Moving Tales of Youth: The Pure Heart (Shonen bidan: Kiyoki kokoro), which I’ve already reviewed.4 The Kobe Film Planet Archive web page also reveals that Uchida shot Moving Tales of Youth in the very same studio in which he had filmed the Kanto shipwreck film, a facility which Kokkatsu had already abandoned after that company went bankrupt – which must have happened very soon after the release of the Kanto film (January 30, 1925, according to the Kobe website), since the other film came out later in the same year, 1925. So, if this information is accurate, Uchida’s Kanto film definitely predates Moving Tales of Youth. And if it also predates the only other extant Uchida movie from this very early period, the animated film Tale of Crab Temple (Kaniman-ji Engi, 1924 or 1925), which is very possible, the Kanto clip would thus be the very earliest surviving footage of any kind directed by Uchida Tomu.

The clip, which lasts exactly three-and-a-half minutes, includes five scenes (excluding title cards) that have no obvious temporal relationship to one another. The sequence of these scenes, with their duration in seconds, is as follows:

0:00 – 0:07: This very brief scene consists of a single, interior (studio) shot, in which an old man and a young girl in traditional dress, both of whom we view again later on, are giving assistance to a sick young man sitting in the foreground – apparently one of the survivors of the shipwreck. He is wearing underwear rather than a uniform and is covered by a heavy blanket. The location is a private home rather than any kind of medical facility, and there is a tea kettle from which steam is emanating that is hanging from a rope in the center of the room. A young boy sits at the left side of the frame. An agitated young child briefly appears, standing on the extreme left of the frame. Because of the faded quality of the footage, it’s difficult to tell what the characters are trying to do.

0:08 – 1:03: This 55-second scene, an exterior shot apparently filmed either in the early evening or at dawn, is by far the most impressive and haunting of the entire clip, despite being, like all the other scenes but one, totally static, without cuts or camera movement of any kind. After an elegant fade-in on the light from a fire, this flame turns out to be a bonfire at the summit of a rocky hill, on a coast overlooking the sea. The striking composition creates three broad main areas of the picture frame: the tall hill at right with several trees and people on it; the sea, with the ship in the distance, at left; and a second, much smaller rocky outcropping in the lower-left quadrant of the frame. (Based on these details, it has been determined that the shot was taken near where a stone monument to the historical disaster currently stands.) Upon the water is a motionless ship listing gently to the right (starboard), representing, of course, the stricken Kanto. This ship may very well be an actual ship filmed in long shot rather than a model, but since Tsubaraya would much later specialize in the creation of such models – particularly for the wartime propaganda film, The War at Sea from Hawaii to Malay (Hawai – Marei oki kaisen, Yamamoto Kajirō, 1942), which recreated the attack on Pearl Harbor so realistically that many Americans after the war believed it was actual footage of the event – one cannot say for certain whether the vessel in this film is real or not. The Yahoo article has noted that the image is not realistic, as the sea around the ship is shown as totally calm, rather than turbulent, as it was during the actual event. Around the bonfire, four tiny figures, silhouetted against the fire, move ambiguously. They appear literally as shadows, much too far away from the camera for their faces or even their gender to be determined for certain. The figure at far right soon disappears behind a rock and is lost track of. The other three gesticulate rather wildly at the ship and at one another for nearly a minute. The effect curiously echoes that of the silhouette-animation short, Tale of Crab Temple, which Uchida co-directed at about this time, though the figures around the fire are human performers, not animated cutouts. The image reminds me of the great shot in Earth (Tsuchi, 1939) in which Otsugi’s young friends, after crossing a lake on their way to their new jobs in a nearby factory, disappear into the distance on the opposite shore, as the lonely Otsugi watches. In conception and execution, this is, in my opinion, the first scene Uchida ever created that proved he had the potential to be a great filmmaker.

1:04 – 1:20: The first of three title cards appears. Translated to English, it reads: “And so the villagers worked through the night on the rescue. The power of their love and manly sincerity saved over 50 souls from freezing to death.” (That bit about “manly sincerity” sounds more than a bit odd in this context, since in real life the village women worked at least as hard as the men to save the sailor’s lives.)

1:21 – 1:33: This is a very beautiful shot of the dawning sun rising behind a bank of clouds, regrettably marred by the poor quality of the print. The sun appears, unusually, near the top of the frame, rather than near the bottom, as sunrises in films are usually depicted in my experience. This reminds me of certain shots in Uchida’s Earth.

1:34 – 1:40: The second of the three title cards appears, reading simply: “Dawn breaks.”

1:41 – 3:01: This is the longest scene in the clip and the only one divided into multiple shots. It begins with a shot of three young boys of about ages ten to fourteen, sitting on the floor in a circle and talking, their legs covered by a blanket. The smallest boy of the three reads aloud from a book. (I believe this boy may be the previously-mentioned young actor Mizushima Michio, but I can’t be certain.) The boys seem to be amused by the book’s contents. An old man is visible in the background, in an adjacent room. The scene shifts to a shot of the other room, which appears to be a kitchen, and which is the same setting as the first scene with the sick sailor. This time, however, there’s no sailor, just the old man wearing a cloth cap, and the young woman, who has just entered holding a package. They talk for a short time, but there’s no title card to explain what’s going on. The girl, apparently at the old man’s behest, reluctantly rises and walks into the other room. A third shot shows the girl standing in the same room with the boys, bowing to them, and then abruptly throwing the package down on the blanket before exiting. We never see what’s in the package or what it signifies. When she returns to the kitchen in the fourth shot, the old man laughs at her behavior, and the girl, annoyed, playfully strikes the man on the arm. The gently comic tone of this sequence is bewilderingly incongruous in a film about a real-life maritime disaster. Yet even a casual acquaintance with Uchida’s work shows that he was never averse to mixing comedy with dramatic situations that are anything but funny (for example, in A Bloody Spear at Mt. Fuji). Unfortunately, we don’t have the entire film to judge whether, in this case, this mixture of tones worked.

3:02 – 3:14: The last of the title cards reads, “The joy of resurrection moves them to tears.”

3:14 – 3:30: This final scene of the clip, actually a continuation of the previous one, features three young men, together with the girl, entering the kitchen area from outside and greeting the old man. One of the three is wearing a sailor suit; all appear healthy. (The man in the sailor suit may well have been the same as the sick man in the first scene, though it’s impossible to confirm this.) The boys in the next room, who are visible in the shot, look on with interest as the strangers enter the house. The appearance of the healthy sailor in the footage implies that the rescue effort had already occurred in the past. Is this, then, the film’s “happy ending”?

The fragment’s overall theme of a community of ordinary people banding together to save an imperiled group is very Japanese and would naturally appeal to that people’s ideal of group solidarity, which had been so deeply ingrained in the nation’s culture for centuries. It’s also a theme that Uchida would explore much later in The Eleventh Hour (Dotanba, 1957), in which a group of miners, including a group of Zainichi Koreans, band together to save several of their fellows trapped in a collapsed mine.

The big difference between the 1925 fragment and the 1957 film is that Uchida used the melodramatic situation in the later film to point out the racial discrimination the Korean characters suffered, as well as the dangerous conditions under which miners in general at the time worked, particularly with mine owners pressured to sacrifice safety in order to cut costs, as occurs in the film. There’s no indication of any social criticism in the fragment and, given the Japanese industry at the time, which was still in its “childhood” phase, it’s extremely unlikely that any such critique would have been detectable in the complete film, if it still existed.

From their clothing, it would seem that the villagers depicted in the studio shots are farmers or peasants (that is, tenant farmers). This fact, plus the relationship of the young woman and old man, which faintly recalls that of the teenage girl Otsugi and her grandfather, Uhei, in Earth (1939), evoke memories of that Uchida masterpiece. Finally, the plot involving a sea disaster very strongly recalls the opening scenes of A Fugitive from the Past (1965), though, of course, the shipwreck is much more skillfully filmed in the postwar movie. So we can say that this fragment, in several obvious and subtle ways, foreshadows the great director’s later work.

As far as the fragment’s very static style goes, one should note that not only was the Japanese industry at that point not yet fully up-to-speed with the cinematic innovations that Europe and America had introduced during the same period and earlier, but Uchida personally had barely gotten his feet wet, so to speak, in the film medium, since Giketsu was his fourth credited film and only his second film as solo director.5 So it should not be too surprising how un-cinematic the staging of the action is. Rather, it’s surprising how visually interesting the clip is, particularly that haunting second scene.

In short, this fragment is a mere curio, and a very minor addition to a great moviemaker’s legacy, but a fascinating one.

The author would like to thank Hayley Scanlon for her assistance with translation.

Yahoo article about the fragment (Japanese)

Kobe Planet Film Archive page about the fragment (Japanese)