Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

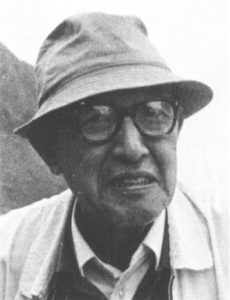

I call this page “a biography” rather than “the biography” of Uchida Tomu, because a definitive biography doesn’t exist and almost certainly never will. One might well argue that a definitive biography of anybody isn’t – can’t be – possible. But whether or not that is so in general, it would be particularly true of this man who was, by a country mile, the most enigmatic of all great Japanese film artists. But at least we can definitely say what an appropriate biography of Uchida Tomu should not be, as illustrated by the (mercifully brief) real-life example below:

“Japanese director Tomu Uchida is best remembered for his moving and extremely realistic docudrama The Earth [sic] (1939). Born in Okayama, Japan, he started out as an actor in silent films in 1920. Three years later, Uchida became a director’s apprentice to such filmmakers as Mizoguchi. In 1927, he made his own directorial bow. For a few years afterward, Uchida focused on directing frothy comedies, but by the late ’30s had become renowned for his realism. Uchida’s work met with disapproval with militaristic government [sic] during WWII and he exiled himself [sic!] to Manchuria, China, where he became a communist and supporter of the local people. In the 1950s, Uchida returned to Japan to resurrect his career. In that period, he became known for his costume dramas. His final film, Swords of Death (1972), was released after his death.”

– Former Allmovie.com listing for Uchida Tomu (subsequently deleted)

That Uchida Tomu is remembered at all by movie fans outside Japan, as indicated by the above passage, must surely be regarded as better than nothing. And to be fair, this summary of his career is probably no more inaccurate than other such capsule biographies of him you’ll find all over the Internet. (And I can’t really fault the author much for its inadequacy, given the paucity of accurate source material available.) However, here is my take on this capsule bio, based upon what I now know about this artist.

“Japanese director Tomu Uchida is best remembered for his moving and extremely realistic docudrama The Earth (1939)…”

On the contrary, I would argue that, in Japan at least, Uchida is best remembered for one of his very last films, the 1965 film noir masterpiece Kiga kaikyō, known in the English-speaking world as A Fugitive from the Past. (A literal translation of the Japanese title would be The Hunger Straits.) As recently as 1999, this movie was judged in a poll of Japanese critics to be the third greatest Japanese film of all time… just ahead of Tokyo Story. (Earth didn’t even appear on that poll.) As for the U.S., Uchida is probably best known here for the only work of his that was, for a time, widely available on DVD in North America: the five-part saga Miyamoto Musashi (first released in Japan in 1961-1965), starring popular samurai-film star Nakamura Kinnosuke.1 There’s no question that Earth – as the title should be translated, rather than “The Earth,” which misleadingly implies “planet Earth” – is one of Uchida’s most important movies. But although it is indeed a “realistic” film, it is not quite a “docudrama” (all the significant roles are played by professional actors) and Uchida in any case definitely did not always work in a realist vein… as The Mad Fox (Koiya koi nasuna koi, 1962) alone proves.

“Born in Okayama, Japan, he started out as an actor in silent films in 1920. Three years later, Uchida became a director’s apprentice to such filmmakers as Mizoguchi. In 1927, he made his own directorial bow.”

Much of the above is not really accurate. Uchida was indeed born in Okayama in southwestern Japan, and he did start his career in movies as an actor in 1920 in the Hollywood-inspired comedy Amateur Club (Amachua kurabu), directed by pioneer filmmaker Thomas Kurihara. But though he may have been partly mentored by Mizoguchi, far more important to his career were Kurihara, the famous novelist Tanizaki Jun’ichirō and the filmmaker Kinugasa Teinosuke, the future director of A Page of Madness (Kurutta ippêji, 1926), Crossroads (Jûjiro, 1928) and Gate of Hell (Jigokumon, 1953). In fact, Uchida’s very first credit as director was for the lost 1922 film Ah, Officer Konishi (Aa, Konishi junsa), which he co-directed with Kinugasa when he was a mere 24 years old.2 In 1927, Uchida made not his first film, but his first film for Nikkatsu, Japan’s oldest major studio. Numerous sources such as this one thus erroneously claim that his directorial debut took place in 1927 rather than 1922: quite a time gap.

“For a few years afterward, Uchida focused on directing frothy comedies, but by the late ’30s [he] had become renowned for his realism…”

The evidence shows that, rather than concentrating exclusively on comedies, Uchida made a wide variety of movies from his earliest years, something this supremely restless artist would never cease to do throughout his career. It so happens that of his very earliest surviving live-action films, the most prominent is the slapstick comedy Sweat (Kigeki: Ase) from 1929. But the previous year, he’d made a chillingly prophetic science-fiction drama, now lost, as described by Peter B. High in his superb book The Imperial Screen: namely, The World Turns, Part 3, which predicted an air invasion from a foreign country, probably the US, which would devastate big cities like Osaka. (The peacetime Japanese audience was not yet ready for such militaristic spectaculars, so the movie flopped.)3 And in 1931, he released the two-part Jan Barujan (Jean Valjean), an adaptation of Victor Hugo’s grim Les Misérables. (This work is also lost.)

Though it’s true that his movies of the mid-to-late 1930’s did become more “realistic” and philosophically and politically “serious,” that statement must also be qualified. Unending Advance (1937), for example, one of his most acclaimed prewar films, intriguingly combines realistic sequences with pure fantasy, and freely mixes comic, satirical and tragic tones. This willingness to blend seemingly incongruous elements appears to have been one of the features of Uchida’s work that most intrigued critics, even in this early stage of his career.

“Uchida’s work met with disapproval with [the] militaristic government during WWII and he exiled himself to Manchuria, China…”

This is totally untrue. I can’t find any evidence at all that the Fascist government frowned upon this director’s work. It’s even been claimed that the government invited the director to go to Manchuria, though this was probably not the case. His 1939 movie, Earth, was even publicly endorsed by the Ministry of Education. This victimization narrative appears to be an attempt to make Uchida into some kind of minor martyr to Fascism, which he most certainly was not. And his departure for Manchuria was, whether invited or not, a personal decision forced on him by nobody.

“… he became a communist and supporter of the local [Chinese] people…”

The question of Uchida’s politics is an extremely complicated one. See the section titled “China Adventure” later in this essay for some elucidation on this issue.

“In the 1950s, Uchida returned to Japan to resurrect his career. In that period, he became known for his costume dramas…”

After he came back to Japan, Uchida did indeed make more jidai-geki films (“costume dramas”) than any other type of movie, and he was particularly legendary for his mastery of the samurai film. But to focus exclusively on those movies at the expense of others he made at the same time would be to ignore the man’s extraordinary range and distort his legacy. As noted already, in Japan his most famous postwar film is A Fugitive from the Past, a crime thriller set in the decade after World War II. In the 1950s and 1960s, Uchida would create the following works set in 20th Century Japan: an ensemble comedy, Twilight Saloon (Tasogare sakaba, 1955); a trapped-man rescue thriller, Dotanba (1957); a drama about racial prejudice set among the Ainu people of rugged Hokkaidō, The Outsiders (Mori to mizuumi no matsuri, 1958); and a yakuza movie, A Tale of Two Yakuza (Jinsei-gekijo: Hishakaku to Kiratsune, 1968), set in the Taisho era. He even tried his hand at a Naruse-esque domestic melodrama. A Hole of My Own Making (Jibun no ana no nakade, 1955), though, in my opinion, with mixed success.

Furthermore, among his jidai-geki movies, two of his very finest – Chikamatsu’s Love in Osaka (Naniwa no koi no monogatari, 1959) and Hero of the Red-Light District (Yōtō monogatari: Hana no Yoshiwara hyakunin-giri, 1960) – were stories, derived from the classical theater, dealing with the merchant class of feudal times, not the samurai class… though the latter movie concludes with one of the most remarkable swordfights in Japanese Cinema history.

“His final film, Swords of Death (1972), was released after his death.”

Okay: except for the date of the movie’s release, which was actually 1971, this sentence, at least, is true.

If Uchida’s work teaches us anything, it’s that humans are complex animals. My attempt below at a brief biography, based upon what I’ve learned so far, is an attempt to get closer to the complicated truth about the man – if that’s even possible at this point – and about the achievements of this supremely mysterious artist.

Uchida Tsunejirō was born in Okayama, in western Japan, on April 26, 1898. Both his friends and fellow filmmakers Mizoguchi Kenji and Itō Daisuke were also born in 1898, and all three would begin their careers in the boomtown atmosphere of the film industry of the early 1920s. Mizoguchi would die in 1956, a few months after releasing his final film, Street of Shame (Akasen chitai). Uchida and Itō would end their careers at exactly the same time and with the same film: Swords of Death (Shinken shōbu, 1971), which Itō wrote and Uchida directed, and which was released after the latter’s death.

Uchida was the third son in a family of comfortably middle-class shopkeepers: confectioners, to be exact. All the (admittedly meager) evidence suggests that his upbringing could hardly have been more prosaic and conventional for a young person of his era and class. Allegedly, in 1912, at age 14 (the beginning of the liberal Taisho era), he dropped out of Normal School – several sources claim the date was 1914, when he was 16, which seems to me much more likely – and moved to industrial Yokohama.4 He eventually became employed in a piano factory, where he learned how to tune pianos. This skill gave him, though poor himself, access to the households of wealthy, educated clients, since in the Japan of that time only foreigners and rich Japanese could afford a piano.

It was also at the piano factory that his colleagues began to call him Tomu, after the English name “Tom,” referring to him as “Tom from Yokohama,” and the name stuck, eventually becoming his professional given name. As literally every biographical sketch about Uchida tiresomely notes, the kanji characters he used to spell his new name can be translated as “to spit out dreams”… or, less decorously, “to vomit dreams.” What’s in a name? It may be a mistake to make too much of this, but it’s a fact that almost as soon as he adopted his Westernized moniker, he began to leave behind forever the middle-class world in which he’d grown up. His life would never again be ordinary.

A vivid description of this early period of his life has been given by Craig Watts in his important article about A Bloody Spear at Mount Fuji: “Tomu scraped by financially, eating ‘sauce rice’ and living with friends, who despite their poverty were interested in drinking, dressing fashionably, and speaking English.”5 Uchida was the sort of intelligent, attractive and ambitious young man who seems naturally to attract mentors. One such powerful mentor was the novelist Tanizaki Jun’ichirō. Though he was only twelve years Uchida’s senior, Tanizaki, while the future director was still a schoolboy, had made his literary debut in 1909 at age 23, and by the time Uchida met him, probably sometime in the late 1910s, he had already established a reputation as an important writer of fiction.

Like other important Japanese writers of the day – such as future Nobel laureate Kawabata Yasunari, who would later compose the screen story upon which the script for Kinugasa Teinosuke’s 1926 avant-garde classic, A Page of Madness (Kurutta Ichipeiji), was based – Tanizaki was fascinated by the new medium of cinema and its artistic and commercial possibilities. In 1920, Tanizaki was hired as a literary consultant for the rising studio Taishō Katsuei, known as “Taikatsu”, originally co-founded, under another name, by actor/director Thomas Kurihara (real name: Kurihara Kisaburō). In that year, after Uchida had finished his military service, he was invited by Tanizaki to join Taikatsu as an actor to appear in the aforementioned modern comedy, Amateur Club, a story about middle-class young people vacationing with their families at a resort outside Kamakura, which was written by Tanizaki and directed by Kurihara. Tanizaki’s sister-in-law, actress Hayama Michiko, played the leading female role in the film.6

According to an article by Joanne R. Bernardi, this now lost film was completely distinctive even in its opening credits. After the title card listing Tanizaki was shown, the author himself surprisingly appeared onscreen in silhouette, lighting a cigarette and exhaling smoke. This was followed by a shot of the director, Thomas Kurihara, similarly in silhouette. In this way, the author and the director cleverly positioned themselves as the true stars of the picture. (Many who viewed the movie at the time, including Uchida himself, later remarked upon this unusual credits sequence in their memories of this era.) Bernardi cites this foregrounding of the writer and director in this film as the beginning of a new emphasis on the importance of both these creative roles in Japanese Cinema… roles which heretofore had been largely ignored by the industry and by film writers in favor of actors. This enhanced status for the director in particular would later have important ramifications for Uchida’s career.7

Another actor cast in this movie was Uchida’s close friend and sometime roommate, Inoue Kintarō. Inoue would go on to direct the 1927 silent film, A Traveler’s Journey of Sorrow (Dochu Hiki), upon which A Bloody Spear at Mount Fuji (Chiyari Fuji), Uchida’s classic 1955 comeback film, would be based. (Unfortunately, Inoue never saw the remake, as he had died the previous year, in 1954.)

Thomas Kurihara was one of several important directors of the time – such as Henry Kotani, Abe Yutaka (also known as “Jack” Abe) and Murata Minoru – who had acquired significant Hollywood experience as actors and technical assistants. After they returned to Japan, this professional background gave them all a great deal of clout in the Japanese industry, as its executives seem to have assumed that the Western way of doing things, including how to make a movie, was invariably better. And Kurihara, like Tanizaki, supported the “Pure Film Movement” (Jun’eigageki undō), which wanted to move Japanese cinema as far away as possible from the country’s theatrical traditions, such as kabuki and shinpa – the two dominant influences on the very earliest Japanese films – towards a realistic style closer to the Western films they admired. (Some sources claim that Uchida worked briefly as an assistant director for Kurihara, which served as preparation for his 1922 debut as director.)

Uchida shared this orientation towards the West. As his embrace of the “Tom” nickname would imply, he was a fan, like many of the well-to-do people he cultivated, of Anglo-American culture. His embrace of comedy and sports themes in many of the silent films he would direct in the late 1920s and after for Nikkatsu demonstrates the impact upon his imagination of Hollywood, which also strongly influenced other filmmakers of his generation, particularly Ozu. Echoes of memorable scenes from American films can be found in Uchida’s movies as late as the 1950s – such as the conclusion of The Outsiders (1958), which unmistakably alludes to George Stevens’ 1953 movie, Shane – long after his mania for all things Western had otherwise cooled.

As already mentioned, Uchida made his directorial debut in 1922 as co-director with Kinugasa of Ah, Officer Konishi, for a company led by cinema pioneer Makino Shōzō. Then in September 1923, Japan was ravaged by the Great Kantō Earthquake: the most destructive natural disaster in the nation’s history. By all accounts, it had a life-changing effect on Uchida. Like many Tokyoites, he lost his home and all his possessions. He then wandered blindly through a devastated city, winding up in the lower-class Asakusa district.

But as would happen more than once in his career, a catastrophic event over which he had no control became for him an opportunity to embark on a fascinating new experience. The man who had cultivated well-to-do friends like the distinguished author Tanizaki started hanging out with the working class, touring with a group of itinerant actors and even joining a construction crew. (This experience would later be reflected in his 1929 silent film Sweat (Ase), a comedy about a down-on-his-luck tycoon who’s forced to work on a construction project.) Uchida would later claim that this period was crucial to his artistic development. It would certainly be important to his political development: by the 1930s, he would become at least as noted for his left-wing views as Mizoguchi was.

(Continued on page 2)