Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

(Continued from Page 2)

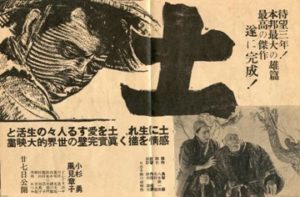

But in 1937, all this drama relating to Unending Advance was in the future. Riding high on the acclaim of his most recent films, Uchida set out to realize his most ambitious project yet: an adaptation of Nagatsuka Takashi’s famous 1912 epic novel about Meiji-era tenant farmers, Earth.1 This was a daunting undertaking, because much of the story was to be shot on location, with all four seasons of its rural setting captured on film, meaning that shooting would require at least a year.

According to Richie and Anderson (and many other sources echoing them), Nikkatsu turned Uchida’s project down flat, whereupon he defied the studio and went ahead with the production anyway, using a clandestine crew and siphoning funding Nikkatsu had intended for other, more commercial movies. By the time the studio got wind of what was happening, it was too late: most of the movie had already been shot, and the executives couldn’t cancel it without losing face with studio personnel who had supported Uchida and helped in its making. So they decided to release Earth anyway – to much critical and commercial success.2

The story above sounds too good to be true, and it is – but it turns out to be only a slight exaggeration of the truth. I relate the full amazing story (as I understand it) in my blog’s review of Earth . Suffice it to say, the movie, when finally released, did become a surprise hit. Earth also became Uchida’s second film in three years to be awarded the “Best One” prize in the KJ poll. Though it revealed the extensive influence of European Cinema on its creator – particularly Soviet and German film – it was, in the context of Japanese Cinema, utterly unique in its combination of extreme realism and baroque stylization. Though it vaguely influenced some subsequent films – particularly Shindo Kaneto’s The Naked Island (Hadaka no shima, 1960) – it has had no real successors: a mostly successful but unrepeatable experiment.3

About a month before the film’s release in April 1939, the Japanese parliament passed the Film Law, which essentially made the film industry a partner – almost a subsidiary – of the government.4 With this and other cultural and legal changes, the stage was set for a completely totalitarian society, in which only the Fascist government’s false version of reality would ever be disseminated, and filmmakers had to comply or be silenced, one way or another.

Japanese directors during this turbulent time responded in very different ways to the challenge of the era, when directors had to make films that were, at least in part, Fascist propaganda if they were to work at all. Gosho Heinosuke, according to his English-language biographer Arthur Nolletti, Jr., made very few films during this period, consistently turning their plots in subtle ways away from official propaganda towards the humanist values he refused to abandon (and was taken off at least one project as a result). He was probably saved from official censure only by his famously fragile health, and he resumed his career in earnest only after the war was over.5 Ozu Yasujirō, though his work during this period did contain some unfortunate propaganda, got away with telling the same gently ironic stories he had always told, and did so to great acclaim.6

Naruse Mikio took refuge in performing arts films set in the past – which was one genre that even the strict Japanese censors found unobjectionable – including The Song Lantern (Uta Andon, 1943) and the lost 1944 film The Way of Drama (Shibaido). (Naruse would later admit that even during the war he couldn’t bring himself to depict soldiers in his films.)7 The former leftist Mizoguchi Kenji, after having made two failed Fascist propaganda films – The Dawn of Manchuria and Mongolia (Mammo Kenkoku no Reimei, 1932) and The Song of the Camp (Roei no uta, 1938) – retreated, like Naruse, to the performing arts film (The Life of an Actor (Geidō ichidai otoko, 1941), and then branched out into his own versions of the much-filmed legends of the forty-seven ronin (The Loyal 47 Ronin, Parts I and II (Genroku Chushingura), 1941-42) and Miyamoto Musashi (Miyamoto Musashi, 1944).8 9 And the documentary filmmaker Kamei Fumio couldn’t stop telling the truth about the war, however unintentionally, and was rewarded with a year in prison for his pains, the only Japanese filmmaker ever to be punished in this way.10

But most directors, even some of the very greatest, willingly bent with the rightward wind. Kurosawa Akira made a hilariously dumb anti-Western propaganda film, Sugata Sanshiro II (1945), as the sequel to his brilliant debut, Sugata Sanshiro (1943), as well as a depressingly militaristic home front film, The Most Beautiful (1944).11 And even past (and future) Communist directors like Yamamoto Satsuo and Imai Tadashi created some of the most “patriotic” (i.e., right-wing) productions during those years, such as Winged Victory (Yamamoto, 1942, with a script by Kurosawa) and Suicide Troops of the Watchtower (Imai, 1943), though Imai later called his wartime films, “the biggest mistake of my life.”12 13

Uchida, characteristically, reacted to the siren song of Fascism in a way quite different from any of his peers. This man, barely 40, who had become, in the space of less than 20 years, one of Japan’s top directors, and who lived and breathed filmmaking, would complete only two movies during the 1940s: the three-part period movie History (1940) about the Boshin War (the first part of which ranked seventh in the 1940 KJ poll), and, for Shochiku, another period film, Suneemon Tori (1942) – both now lost. He had quit Nikkatsu and, in the worst possible political climate, tried to set up his own production company, which predictably failed. Eventually, near the very end of the war, he decided to go to Japan’s notorious studio in occupied Manchuria on the Chinese mainland – The Manchurian Film Association, known as “Manei” for short – partly to attempt to continue directing movies, but managed to make not a single one. When the war ended, he elected to remain in China, again without making any films. When he resumed his career long after the war, it would be in a totally reborn Japan… and as a totally reborn moviemaker.

(Continued on Page 4)