Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

(Continued from Page 3)

Uchida Tomu’s years in China, which lasted from the spring of 1945 until October 1953 – about eight-and-a-half years – comprise the most frustratingly opaque period of the great director’s life. The equivalent in rock music history would be the tumultuous and confusing January 1969 recording sessions that resulted in The Beatles’ penultimate album Let It Be, the period in the band’s career most shrouded in mystery and speculation. The difference is that the group emerged from a tense creative period with a (flawed) work of art, while Uchida had absolutely nothing to show for his near-decade in the wilderness.

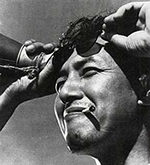

Or did he? A remarkable October 1953 photo, recording his return to his native land, shows the frail filmmaker – looking at least ten years older than his actual age (55), and walking with the aid of a cane, his wife by his side – smiling broadly, apparently a very happy man, which he most definitely does not seem to be in the 1936 Japan Film Directors Society photo alluded to earlier in this biography, which was taken at a time (age 37) when he still had his youth and his health. What’s clear is that his ordeal had not enervated Uchida, but had strangely energized him. How did this happen?

To discuss this interlude in my subject’s life, it will first be necessary to summarize the fascinating history of the Manchurian Film Association (Manshu Eiga Kyokai), better known as “Manei,” located on the Chinese mainland at the city now called Changchun, but known at the time as, in Chinese, Hsinking or, in Japanese, Shinkyō. (The name, in both languages, means “new capital,” as it was indeed the new capital of the Japanese puppet state of Manchukuo.) For background information on this studio, I’m indebted to Peter B. High’s definitive history of the Japanese film industry during wartime, The Imperial Screen, and to Michael Baskett’s The Attractive Empire: Transnational Film Culture in Imperial Japan (see notes below). I’ve also augmented the text with some material adapted from Wikipedia articles.

Manei was created for two purposes: to make films in a Manchurian setting for both pure entertainment and propaganda purposes for the Japanese audience and, more importantly, to make entertaining propaganda and educational films for the Manchurians themselves. Uchida’s old boss at Nikkatsu, Negishi Kan’ichi, became head of Manei the year after its founding in 1937, but in 1939 he was replaced by the sinister Amakasu Masahiko,1 a man whom Peter B. High calls “a Japanese Heinrich Himmler” because of the strange contrast between his mild outward manner and fearsome reputation. 2 Amakasu had been convicted, while serving as a lieutenant in the military police during the chaos following the Great Kantō Earthquake of September 1923, of the brutal killing, by torture or strangulation, of the anarchist radical Ōsugi Sakae; of his lover, the anarcho-feminist Itō Noe; and of Ōsugi’s six-year-old nephew, Tachibana Munekazu, who had been born in Oregon. (Their bodies had been dumped down an old abandoned well.) 3 4

There is evidence to suggest that Amakasu might have taken the rap to cover up for the collective guilt of the military police. But there’s no question that he was directly implicated in the heinous murders, and the crime was forever after known as the Amakasu Incident. Despite the fact that these killings, particularly of the child, caused outrage in Japan, at a time when the Left still had many sympathizers, Amakasu served only three years of his ten-year sentence, because of an imperial pardon he received in 1926.5 (Public opinion at that time would never have questioned the decisions of the Emperor.)

Amakasu soon after went to Manchuria, where he became involved in even more serious mischief. After participating in opium smuggling, he apparently played a role in the false flag operation known as the Mukden Incident, in which Japanese military officers blamed Chinese agitators for a dynamite explosion they themselves had set. The incident was used as the pretext for the Japanese invasion of Manchuria – thus initiating, for Japan, a state of war that was to last 14 years – and the establishment of a puppet state in the area the Japanese now called Manchukuo.6

Despite his utter lack of experience in the film world, in 1939 Amakasu was appointed (as previously mentioned) the new head of Manei, a decision that, because of the man’s brutal reputation, was met with astonishment and even outrage by some expatriate Japanese. Surprisingly, though, this unorthodox studio chief turned out to be an admirably fair-minded employer. He raised the salaries of Japanese film workers, and never abused the studio’s Chinese employees, treating them as equals to the extent possible. When powerful visiting officials expected, as their right, to be “entertained” by the studio’s actresses, as was customary in other Japanese studios in occupied Asia, Amakusa refused to permit it, declaring “actresses are not geisha” – and because he was so feared, no one ever tried to go over his head. Most importantly, relating to the subject of this biography, the ultra-rightist Amakasu didn’t discriminate against left-leaning film workers. On the contrary, for him the only criteria for employment at Manei were professional competence and dedication to the organization’s Empire-building mission. Paradoxically then, this studio, led by one of Japan’s most fanatical and violent Fascists, proved something of a haven for Communist or “pink” film professionals who were no longer welcome in their rigidly militaristic home country.7 8

Sometime in the last years of the war, Uchida, still based in Japan, took up a new project: a war film that would be a co-production between one of the major Japanese studios, Shochiku, and Manei. He collaborated with the ambitious young screenwriter Shindo Kaneto (still years away from directing his own first film) on the script of a movie about a famous Japanese tank corps on the China front, and they visited Manchuria together to research their subject. But somehow he and Shindo, despite working on numerous drafts, could never see eye to eye about the project, or perhaps their work failed to satisfy Uchida’s exacting standards. And it may be that, in the ever-worsening situation of the war, with resources for the film industry becoming ever scarcer, Uchida’s goal of a movie on such an epic scale was simply unrealistic. As he wistfully notes in his autobiography, “the reality of ‘the great war film’ ended at the dream stage.”9

Uchida was a man who took obligations seriously. This particular tank corps had made an outstanding contribution to the war, which he by this point enthusiastically supported. (During this period, he shared with an acquaintance the opinion that it would be an excellent thing to die for Japan.)10 The army had put funds into the project and Uchida had, in his own mind, let these brave soldiers down, and thus felt he had no choice but to express his regrets. But he then made a very odd decision: instead of writing a letter of apology, in May 1945 he journeyed to Manei personally, leaving his wife and children behind in Japan. He would not see them again for eight-and-a-half years.

It is at that point in the narrative that a remarkable woman enters the picture. Kishi Fumiko was one of those Japanese cinema professionals for whom filmmaking was quite literally their whole lives. As a Japan Times article from October 2015 (unfortunately no longer available online), entitled “New book chronicles influential short-lived Manchukuo film studio,” relates, she was born in the northeastern Chinese province of Liaoning to Japanese parents in 1920. Her father died when she was young, forcing her to make her own way at an early age. At only 15, she became an assistant film editor for the small studio Daiichi Eiga, and it was there, in 1936, that she helped edit two of Mizoguchi Kenji’s early masterpieces, Osaka Elegy (Naniwa Erejī) and Sisters of the Gion (Gion no kyōdai). (Actress Yamada Isuzu, who stars in both films, though still a teenager at the time, was three years older than Kishi.) In 1939, she followed her brother, a camera operator, to Manei. And, now in her mid-twenties, with a decade’s experience in the industry behind her, she was still there six years later when Uchida arrived from Japan.

Kishi Fumiko: “The great director Uchida Tomu, who had made such well-regarded films as A Living Doll, Unending Advance, and Earth at Nikkatsu, suddenly showed up at Manei. He came to stay with the cameraman Kiga Seigo. Why would a director of Uchida’s stature have come all the way to Manei at that particular moment? I found it very strange.

“Anyway, there was a rumor he came to apologize in person because the script for a co-production, Rikusen no Hana: Senshatai [Land Battle of the Flower Tank Corps], remained continually unfinished. But then rather than head straight back to Japan, it seems he got the idea from Amakasu to go and see the [Manchurian] terrain. I don’t know why, but I found that even stranger.”11

So at least one person who was working at Manei at the time found Uchida’s awkwardly-timed arrival peculiar. The passage strongly suggests that, though he didn’t admit it to anyone at the time, he had come to Manei with at least the tentative intention of staying awhile to work. It should also be noted that, by this time, as almost every major Japanese city was being bombed by the Allies, and Okinawa was on the verge of falling to the Americans, it was obvious to everyone who was not in deep denial (though many, of course, were) that Japan was soon going to lose the war.

Part of the explanation for Uchida’s subsequent behavior lies in Amakasu’s strange hold upon his imagination. Of warrior heritage, Amakasu seemed, in his extreme militarist stance, like a samurai out of the distant past come to life, and this fascinated and intimidated the director. According to Uchida’s autobiography, as related by Craig Watts, at their first meeting he was so nervous in the studio head’s presence that the only thing he could think of to break the ice was to ask the man for a cigar. In a YouTube video, his son, Yusaku, claims that Amakasu then offered him a job as an advisor to Manei, and he accepted. Thus, a brief visit that was supposed to last days at most stretched into months. And it’s very possible that Uchida, even in those desperate times, held onto the slender hope that he could film at least one project at Manei, perhaps one less challenging, and less expensive, than the aborted tank movie.

In August, Japan’s defeat intervened. For a time, Amakasu contemplated making a hopeless stand against the invading Soviet armies; then he offered poison to all the evacuating families in case of capture by the enemy. There’s also the rumor that he had seriously considered collecting together the studio’s entire film stock to create a huge bonfire to destroy Manei and everyone in it, so that neither the Soviets nor the Communist Chinese could ever use the studio, though I can’t quite believe this story.

In the end, though, on August 20, five days after the Emperor announced his country’s surrender, Amakasu killed himself alone with potassium cyanide, in Uchida’s presence.12 According to Uchida’s son, Uchida Yusaku, in the YouTube video cited above, Tomu tried in vain to revive Amakasu through artificial resuscitation. The studio head left a suicide note explaining that, because he’d failed the Emperor, he wasn’t worthy of committing traditional seppuku.13 14 One writer recalled that over 3000 people – both Japanese and Chinese – attended Amakasu’s funeral.

What followed was pure chaos, even by the usual standards of war. The Soviet Army invaded the studio, looting it of much of its precious equipment, and a tug of war ensued between the Communist Chinese and Kuomintang (Nationalist) forces, each trying to take over the studio, which was considered a major prize in the propaganda war. By April 1946, the Soviet Army turned the studio over to the Chinese Communist forces, but the Kuomintang was still threatening to overthrow them.

Uchida’s son in the video mentioned above relates an odd story from about this time that his father later told him. In the canteen at the studio, Uchida encountered an old man, “a true dandy,” very courteous, who was a cadre for the Chinese Communist Party. This man greatly impressed him. At that moment, the Japanese director, despite his fame and success in his native land, was seized with a desire to remain in China and observe the momentous changes in that country.

The Communists’ plan, according to Uchida’s son, was to repatriate the Japanese film personnel, and a cargo train was provided to evacuate them from the besieged city. Uchida had expressed a desire to get on that train, but, literally at the last minute, he changed his mind. He announced to his stunned compatriots that he was staying in China. He then walked away towards the plains of Manchuria as the train departed… a classic movie scene if ever there was one.

The great mystery of Uchida’s life, therefore, was not so much why he had come to Manchuria in the first place, since many leftists and former leftists (as we’ve already noted) had done the same. It was why he chose to remain in the country for eight years after Amakasu’s suicide, when he could easily have consented to be evacuated with most of his colleagues – and as the Communists wanted him to do. There are four basic theories as to why this happened:

As far as I can tell from my research into this period of Uchida’s life, the most accurate answer would be… (5) all of the above, or rather, each of the above theories is partly true and partly untrue. Uchida was indeed held prisoner in China, first by the Soviets, and then by the Chinese Communists, in the sense that, under the rule of both governments, he was not free to live wherever he wanted or to do whatever he pleased. And the Communists, under their “retrenchment” policy (more on that later) did force the community of Japanese expatriates to do dangerous manual labor, including work in coal mines – though Uchida chose to do this work despite the government exempting him from such labor.

Uchida did, eventually, teach Chinese (and Korean) movie professionals the most modern film techniques known to him, with Kishi Fumiko’s help, and though he clearly enjoyed this work, he may have been partly motivated by guilt at what Japan had done to China. Furthermore, many friends of his believed that, even after Japan’s defeat, Uchida had hoped to make a film in China, and it’s entirely possible that he gave up this dream only when he realized that the Chinese would only let Communist Party members direct films, and Uchida either was not allowed to join the Party or chose not to.

And finally, according to Craig Watts, although he was never, technically, a Communist, Uchida was forced in China to attend Communist study meetings, in which he was schooled in Maoist thought. According to Kishi, he was particularly fascinated by Mao’s famous text, On Contradiction, and this became a kind of Bible to him,15 greatly influencing his postwar work – as we shall see.

But to get back to our story… the situation in Hsinking soon became untenable for the Chinese Communist forces, and they decided to retreat towards the north. The choice the Japanese had to make – and surprisingly many of them, besides Uchida, had opted to stay behind while most of their countrymen had returned to Japan – was either to remain in the city and wait for the Kuomintang or go north with the Red Army.

The fact that they chose the latter course was largely due to the persuasiveness of Uchida and his fellow director (and fellow leftist), Kimura Sotoji, as Kishi makes clear below. Kimura Sotoji, born in 1903, was an important director of the prewar era. Like Uchida, he was associated with the left-wing keikō eiga (left tendency) movement of the late 1920s and early 1930s, and his lost 1933 film, Youth Across the River (Kawamukō no seishun) has been called the last proletarian film made before the end of the war. His most famous film is the original version of Older Brother, Younger Sister (Ani Imoto, 1936), which was remade in 1953 by Naruse Mikio. This film survives, and I’ve seen a version without subtitles on YouTube, as well as a brief clip of it (with subtitles) in Shindo Kaneto’s fascinating 1988 documentary Sakura-tai Chiru (Fall of the Cherry Blossom Corps). He returned from China in 1953 (the same year as Uchida), and continued making films until 1976; he died in 1988.16

The two great directors Uchida Tomu and Kimura Sotoji’s declaration that they’d do as [Chinese Communist author] Shu Qun suggested [that is, go north with the Communists] had a big impact on everyone’s choices. Many of the Japanese filmmakers were inclined to go along with the two respected directors.17

The caravan of film people who then left Hsinking for the north must have made quite an impressive spectacle, as Kishi relates the scene.

The line of horse-drawn carts stretched out endlessly over two kilometres from the studio all the way to Southern Hsinking Station. The sight of the carriages running through the fields as the sun set was just like a scene from a movie. Uchida remarked to me that he’d like to turn it into a film someday [italics mine].18

The above passage strongly suggests that at least one reason for his mysterious decision to remain in China was to seek inspiration as a creative artist. For Uchida, there could be no more romantic situation than a nation rebuilding itself into a brand-new revolutionary society out of the ruins of war, and China represented a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to witness such an event firsthand. This would seem to be an extreme way for an artist to overcome a creative block, but the clandestine filming of Earth had already proven that Uchida was never unwilling to resort to extreme measures in the service of his art.

This motive is partly confirmed by a later passage in Kishi’s book.

It was then [when the Japanese had arrived at Harbin] that I started to think again about why Uchida and Kimura had decided to come north so quickly. Expressive people are extremely curious. Because they were both directors who’d made left-wing tendency films, they had a strong desire to observe a communist society with their own eyes.19

It should be noted that Uchida hadn’t totally forgotten his loved ones back home. On the contrary…

Anyone could see that Uchida should return to Japan. Deep down, he was conflicted. He had a family waiting for him back home, but finding himself in the middle of the Chinese Revolution, he also had a strong desire to witness it with his own eyes rather than leaving halfway through.20

(Continued on page 5)