Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

(Continue from Page 6)

1966 and 1967 were the first years since 1954 not to see the release of at least one movie directed by Uchida Tomu. In all likelihood, the one-two punch of the Musashi series and A Fugitive from the Past had physically and emotionally drained and devastated him. Also, Uchida was on the outs with his studio. Tōei had tampered with the final edit of Fugitive without his permission, removing 25 minutes from the director’s cut – repeating, less drastically, the crime Nikkatsu had committed against Unending Advance. It’s not clear what changes were ultimately made, but the possibility that Fugitive might have been an even greater masterpiece if Tōei had released Uchida’s uncut version (which is nine minutes longer than the longest version we now have) amazes me.

After finishing the final installment of the Musashi Miyamoto series, Uchida was free of his commitment to Tōei and could at last begin to operate as a freelance director, which he had always longed to do. Yet, though other studios made tentative offers, none of these materialized into anything concrete, and as far as his most commercial project, a proposed yakuza film, was concerned, only Tōei was interested, as the studio had begun to specialize in such films since 1963. Thus, Uchida wound up working again for Tōei for what turned out to be the last time. Hishakaku and Kiratsune: A Tale of Two Yakuza (Jinsei gekijō: Hishakaku to Kiratsune, 1968), completes the narrative from Ozaki Shiro’s novel that he’d begun with Theater of Life: Youth Version thirty-two years prior. This movie is considered by at least one Internet critic a very important entry in the highly popular yakuza genre of the late 1960s, so historically it’s a significant work, and it’s very competently made. But by Uchida’s standard, I believe it’s a film of secondary importance.

Then there’s the mysterious, short-lived 1969 TV series, Muyōnosuke, based upon a manga by Saitō Tadao. I know nothing about this program, and apparently neither does anybody else, since its listing on IMDB contains no user ratings or reviews at all, and no links to external reviews. Of the 19 episodes for the single season in which this show was broadcast, IMDB claims that Uchida directed “unknown episodes,” which appears to be false (according to Japanese Wikipedia, which lists the actual directors for all episodes), though he did serve as supervising producer. He was also said to be responsible for the casting in the title role of Gorō Ibuki, later to become well-known.

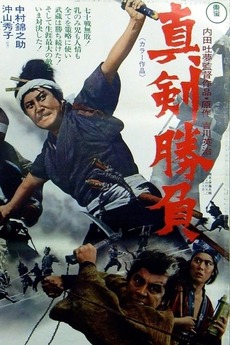

When Uchida then pitched his next project to Toho, a studio for which he’d never before worked, it was for yet another installment of the Miyamoto Musashi saga, with Nakamura Kinnosuke again playing the legendary swordsman. (For Tōei, this must have felt like a deliberate poke in the eye.) The earlier series had been such a box-office sensation that it’s no surprise that Toho decided to greenlight the project. But there was a catch: Uchida was, in fact, dying, as he was suffering at the time, according to screenwriter Suzuki Naoyuki (A Fugitive from the Past), who wrote a book about Uchida, from both advanced cancer and TB.1

This final work – melodramatically titled in English Swords of Death (Shinken shobu, 1972),2 with a screenplay by Uchida’s old friend, Itō Daisuke – is often simply called Musashi Miyamoto VI, as if it were a mere continuation of the five-part Tōei series. However, this strikes me as misleading. Though again based on the famous novel by Yoshikawa Eiji, this work looks and feels totally different from the earlier series. For one thing, Uchida eschews the “classical” style of the Tōei films for something that seems, at least initially, much more raw and direct, more akin to A Fugitive from the Past. And as the movie goes on, without completely breaking with realism, it turns into something nearly as strange as The Mad Fox.

The tone of the movie is keyed to the extraordinarily intense performance of actress Okiyama Hideko as Omaki, the warrior wife of the blacksmith/bandit Baikan, played by Mikuni Rentarō. (This role is as remote from Mikuni’s character of Takuan the priest in the Tōei series as can be imagined.) It’s an action movie with absolutely no heroes. The amoral couple plan to murder Musashi while he’s still a guest under their roof, as revenge for his killing, during the Battle of Sekigahara, of Omaki’s brother. (This, of course, makes no sense: Musashi and the brother were on opposite sides in the battle, and in war, killing the enemy is what one is supposed to do.) Musashi, on the other hand, is depicted here at his most scarily sociopathic. When the couple attacks the samurai with the ball and chain weapon they’ve invented, so that he can’t get close enough with his sword to attack them, he retaliates by stealing their infant son and holding him hostage.

The subsequent standoff is fascinating. Baikan, despite the danger to his child, wants to kill Musashi anyway, because for him the need for vengeance outweighs all other considerations. But the fiercely maternal Omaki protests, so the drama becomes a conflict between husband and wife as much as one between the couple and the samurai. The action is also clearly allegorical: the obligations of the past – revenge, justice – are pitted against the duties of the present towards future generations, symbolized by the baby. In my review of the film, I suggest that the showdown is a metaphor for the Cold War, then at its height. At the conclusion, for example, the maddened Baiken sets fire to the underbrush all around Musashi and his own wife and the child, which in plot terms makes no sense. The image strikes me as a symbol of nuclear Armageddon, an impression reinforced by the title card at the end condemning the violence of the sword, and by extension all violence.

Most critics consider this movie unfinished.3 In fact, Uchida was so ill that he collapsed while filming in April 1970. However, he was worried that he would never recover in time to be able to match the exterior location footage, due to the change of season. So he literally rose from his deathbed to complete the sequence he’d begun.4 He then returned to his hospital room to edit the footage, as he’d had all his editing equipment moved in there. Suzuki, the scriptwriter, insists that Uchida did in fact finish the film to his satisfaction in June, several weeks before his death on August 7.5 Whether one believes Suzuki or not, the film is a remarkable, unique work.

The movie was entered posthumously in the 1972 Taormina International Film Festival and won the Golden Charybdis – the only international festival prize Uchida ever received.

Uchida is buried in the Wadabori Byosho Mausoleum, part of the Tsukiji Honganji Buddhist Temple, in Suginami Ward in Tokyo.

In material terms, Uchida left a scant – indeed, appallingly paltry – legacy. In his last days, knowing he was near the end, he had gotten the idea into his head that because, as the saying goes, “you can’t take it with you,” he’d distribute before his passing all his earthly wealth and possessions to his wife, friends and associates. Thus, when he died, his entire estate totaled, in yen, the equivalent of about six-and-a-half dollars.6

As a man and an artist, his legacy was infinitely richer, but also far more problematic. Even now, I can’t say for certain what his politics were during his later career. Galbraith, in his DVD commentary to the Musashi series, quotes Uchida from his autobiography, who in turn quotes approvingly the Tōei producer Makino Mitsuo, who said, “I’m not a Red; I’m not a White; I’m a member of the Japanese Filmmaking Party.”7 In view of, among other evidence, his obsession with Mao’s writings, this would seem to have been an evasion… but maybe it wasn’t. Once, when Kishi Fumiko visited him after the war, she remarked to him about Mao’s book On Contradiction, “No matter how many times you read that book, you’ll never find an answer that can convince you.”8 In the end, he may have been as politically restless as he was artistically restless, unwilling, or perhaps unable, to choose between ideologies.

The critic Isaiah Berlin, in his famous essay The Hedgehog and the Fox, cleverly divided the world’s literary artists and philosophers into hedgehogs and foxes, inspired by the ancient proverb, “the fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing.” This division is based upon whether the worldview of a particular artist or thinker can be reduced to a single, unified vision (that of a “hedgehog”), or whether the individual’s view of the world is multifarious and can’t be reduced to a single system or truth (that of a “fox”). According to this theory, Dante, with his unified religious cosmos, as illustrated in The Divine Comedy, was a “hedgehog,” and Shakespeare, with his dramatization of many conflicting, seemingly equally valid truths, was a “fox.” Berlin’s essay, which was about Leo Tolstoy, claimed that the great Russian writer was a “fox” who wanted to be a “hedgehog,” but could never quite force himself to become one.

If we study the filmmakers of Uchida’s generation, we discover that quite a few of them were, artistically speaking, “hedgehogs.” Mizoguchi and, particularly, Ozu, for example, tended to restrict themselves to a single subject matter, moral vision and stylistic approach. (This was arguably also true, but to a somewhat lesser extent, of Naruse Mikio and Shimizu Hiroshi.) Uchida, with his extremely broad variety of genres, subjects, tones and styles (even in the prewar period), was obviously not like this at all. In fact, he more closely resembled the “fox” directors of the following filmmaking generation, who came of age as artists during the war or shortly thereafter, particularly Kurosawa Akira, Kinoshita Keisuke, Ichikawa Kon and Kobayashi Masaki – though it could be argued that Uchida went beyond even those artists as far as creative range is concerned.

Yet, not unlike Tolstoy, he seems always to have sought some unifying (male) thinker or leader who could deliver him from the forest of conflicting impulses and choices in which he seems sometimes to have become lost. That may help to explain his youthful attachment to older mentors, as well as his later devotion to the sinister Amakasu and even to Chairman Mao.

In the end, almost against his will, Uchida – the Sane Fox – retained many creative selves, not just one, but this makes his work gloriously rich and complex. One can never get tired of his films as one might conceivably get tired of, say, Ozu’s movies, because if there’s an Uchida genre (e.g., the samurai film) or style (e.g., realism) that no longer inspires pleasure, one can always choose another Uchida movie completely different from or even opposite to that particular type.

In my online review of the 2016 Museum of Modern Art Uchida retrospective (since removed), I compared Uchida’s situation as an unknown master to that of Jean-Pierre Melville, who, prior to the early 1980s, was still an obscure figure outside France. (Today, of course, Melville is revered everywhere, with a secure place not only in the French but in the global cinematic pantheon.) But the comparison between the great French moviemaker and the great Japanese one is a bit misleading. In the end, Melville excelled at only two kinds of movie – the crime film and the war film, with only one other feature, the Cocteau adaptation Les Enfants Terribles (1950), as the exception proving the rule – whereas Uchida not only worked in many different genres, but made all of them his own.

In my own personal canon of Japanese Cinema, which need not be anybody else’s, he appears as the sixth greatest director, after (in order) Kurosawa, Ozu, Mizoguchi, Naruse and Kobayashi.9 That ranking may not seem very impressive, but when one keeps in mind that I’ve rated him higher than literally dozens of wonderful moviemakers that Japan has produced over a century of astounding cinematic productivity, my respect and admiration for the man should be clear.

Several critics have attempted to turn Uchida’s greatest strength into a kind of drawback, even to the point of labeling him an impersonal artist because he made so many different sorts of movies. I hope these notes – and the reviews of the individual films themselves – go some way towards dispelling this notion. True, this director didn’t have one style or theme or obsession. But he did have a number of styles and themes and obsessions unique to him, which one can detect from film to film. In other words, he was an artist, not just a more-or-less superior craftsman.10

On a closing note: a motif one can’t fail to notice from viewing a lot of Uchida’s work is his concern for the young. Many of his heroes – Gonpachi the spear carrier in A Bloody Spear at Mount Fuji, Byakki the Phoenix in The Outsiders, Musashi in the Tōei series – have child sidekicks who share their adventures. The brothels of ancient Osaka and Edo, as depicted in Chikamatsu’s Love in Osaka and A Hero of the Red-Light District, are filled with innocent girl-children, preparing themselves to take the places of the adult courtesans. The young daughter Otsugi in Earth is central to the narrative of that film, both as the main witness to her father’s degradation and as his savior, and a roguish child is the protagonist of The Horse Boy. And it’s sometimes very dangerous to be a kid in Uchida’s world, as proven by the gory death, at Musashi’s hands, of the very young head of the rival Yoshioka clan in the fourth installment (1964) of the Miyamoto Musashi series.

The man who, while in China, had taken under his wing two orphaned children of a woman totally unrelated to him by blood or marriage and raised them as his own, had a special preoccupation with the care and safety of children. And in our world, where young people with knowledge of such terrifying modern problems as climate change, racial injustice and war are fighting for their futures – indeed, for their very lives – Uchida’s concern, I believe, must now become our own.