Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

(Continued from Page 2)

This movie is not just a classic – and one of the very best films of Japan’s best cinematic decade, the 1950s – but for those film buffs totally unfamiliar with the films of Uchida Tomu, it’s the perfect entry point to his work. (Earth, because of the wretched condition of the surviving print, its extremely dark cinematography and its grim subject matter, is probably the very worst entry point for the Uchida novice, despite the fact that it, too, is a masterpiece.) A Bloody Spear at Mount Fuji combines all the director’s virtues as perhaps no other single movie does: his mastery of narrative pacing, his eye for painterly compositions, his extraordinary skill with actors in a large ensemble, his flair for broad comedy, his biting irony and wit, and his inspired staging of action sequences, in which I think only Kurosawa and, perhaps, Kobayashi can be called his superiors.

As already noted, Uchida had not sought to make this film. It had fallen into his lap from above, as it were, when his friend Shimizu Hiroshi deliberately dropped out so he could take over. Yet the fact that this particularly difficult project became his comeback picture was appropriate, because of his lifelong habit of eagerly embracing challenging assignments under pressure. As the synopsis above reveals, his cast of characters was huge, the number of scene changes formidable, the interwoven narrative threads many and complex. Yet there’s hardly any sign of effort or strain in the finished product. The film works as a memorable star vehicle for Kataoka Chiezō – Tōei’s unlikely action star – but also as an ensemble piece for a fine cast of character actors and talented juvenile players, with all performances meshing perfectly.

This is a period road movie that successfully achieves what road movies of any era have always aimed for, which is to bring diverse characters together to fully explore the dramatic possibilities offered by their interaction. As the narrative begins, all the travelers are voyaging on foot and by boat, even Kojūrō the samurai and his retainers, indicating their impoverished status. If Kojūrō were a daimyo – that is, a lord – he would be carried in a palanquin by servants… as is Kyubei the pimp later in the film.

As noted by several commentators, it’s a revealing legacy of the filmmaker’s silent movie training that Uchida introduces the characters to us one by one without any dialogue, so that we can sense what their relationships might be without a single word being spoken. The only commentary is an ironic one by Kosugi Taiichirō’s incongruously jaunty and jazzy musical score, which sounds rather like it belongs in a musical comedy.1

The received wisdom on Uchida is that he started out in the 1920’s as, almost exclusively, a director of comedies (which actually is not, strictly speaking, true, as I’ve noted in my biography of the director), before turning to more serious (read: “socially conscious”) subjects somewhere around the mid-1930s. But A Bloody Spear proves that his original flair for comedy had never deserted him. The surviving 1929 silent film Sweat is mostly slapstick, but this movie is much more subtle, mixing very broad gags – for example, the aristocrats’ roadside picnic – with more delicate, observational humor reminiscent of Ozu, who was, as already noted, an advisor to this production.

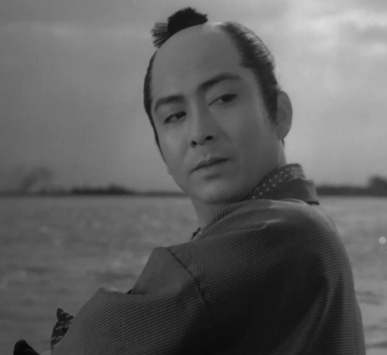

An audience’s reaction to this movie – whether it is enthralled and delighted, or whether it sees this film as just another action picture – will depend largely upon its response to the film’s star, Kataoka Chiezō. I’m not sure which Uchida film first brought Kataoka to my attention – I think it may have been Hero of the Red-Light District – but I recognized at once that he was one of the great film actors. The blogger who calls herself Paghat the Ratgirl admirably caught his appeal in one of her (eccentrically-punctuated) posts:

In his post-Occupation films, Chiezo’s face had become something extraordinary & expressive & versatile, a sort of “poor man’s Takashi Shimura,” no longer the young attractive leading man he still seemed to be even in his thirties. That mature face nevertheless retained something adorable, somewhere between grandfatherly gentleness & patrician authority.

The character Kataoka portrays here, Gonpachi, is not only not a samurai, but a mere spear carrier: someone who’s there to transport his master’s weapon in case the latter should have need of it, but not one who would, under normal circumstances, wield the weapon himself. On Wikipedia, the entry for spear carrier refers to a non-speaking part in a play or opera, a supernumerary, and that’s more or less the nearly superfluous social role Gonpachi fills in this rigidly stratified society.

Thus, a big part of what makes Gonpachi so amusing is his exaggerated sense of self-importance in such a humble position. When Genta out of simple kindness – Gonpachi’s feet are in pain from blisters – offers to carry his spear, Gonpachi rudely rebuffs him, though he has presumably known Genta for years and has no reason to mistrust him. A little later, he will be similarly brusque with Jirō when the boy touches the spear, only to gradually relent when he discovers that the naïve child wants someday to become a spear carrier himself, and thus regards Gonpachi as a role model. Realizing this, Gonpachi becomes so puffed up with pride that he makes a fool of himself in front of the shamisen player, Osumi. His humiliation will be compounded when he later attends the town festival and observes her little girl, Okin, dancing “The Servant’s Dance” – Osumi’s parody of him and his inflated self-image.

Uchida’s strategy in stressing all these major and minor humiliations is to imply that both Gonpachi and his enormous spear are essentially harmless. So it’s a real shock, yet a logical one, when, at the film’s climax, demented with rage, he suddenly turns from lovable clown to avenging demon, brutally butchering the gang of samurai who killed his beloved master. And Kataoka Chiezō, because of that unique combination of gentleness and authority to which Paghat referred in the quote above, is probably the only Japanese actor of his time who could have pulled off this transformation… but only, I think, under Uchida’s guidance.

Kataoka would become one of three actors, all male, who’d dominate Uchida’s postwar output, the other two being Mikuni Rentarō and Nakamura Kinnosuke (later known as Nakamura Yorozuya). For Uchida, I believe that Mikuni represented the dangerously alienating modern world, while Nakamura provided for him a symbolic figure through which the director could critique his own personality and ambitions. But Kataoka embodied for him the solidity of patriarchal tradition, though perceived with the director’s subversive, ironic and ambivalent eye.

The most misunderstood character of the film (by critics anyway) is the alcoholic samurai, Sakawa Kojūrō, whom I believe to be one of Uchida’s great tragic characters. Many commentators call Kojūrō a fool, but this is simply not true: he is actually quite intelligent, aware and self-aware. Sensitive, kind and gentle (except when he’s had too much to drink), he is painfully conscious of the absurdity of his paradoxical position as an impoverished samurai – nominally near the top of the social order because of his class, yet, because of his poverty, simultaneously close to the bottom of it. He’s the opposite of the millionaire that the Tramp befriends in Chaplin’s City Lights, in that the humane side of his personality is revealed only when sober, and his cold, hostile side only when drunk.

Though Kojūrō feels sorely his lack of money, his chief regret isn’t that he cannot advance himself, but that he can’t help others. When he learns of Otane’s plight, he becomes so desperate to find the money to prevent her sale to Kyubei that he tries to pawn what he assumes is the only thing of value (other than the tea bowl, which is sacrosanct) in his possession: Gonpachi’s spear.

The problem is, the spear is also the only thing of value Gonpachi has: in fact, as we’ve noted, it’s the essence of the man’s identity. And yet, while Gonpachi is sleeping, Kojūrō takes the spear to sell to a local merchant without even notifying, much less consulting, his most faithful underling. So even as he displays an admirable lack of class snobbery in his eagerness to aid a mere commoner in her distress, he reveals his class privilege after all, treating his servants as mere pawns for his capricious will.

Kojūrō demonstrates similar high-handedness in the scene near the end of the movie when he enters the tavern courtyard with Genta and insists that his anxious servant share a drink with him – and won’t take no for an answer. Then he engages in a “philosophical” discussion that’s way over the poor servant’s head:

Kojūrō: Genta… you are Genta; you are not Kojūrō.

Genta (bewildered): Eh?

Kojūrō: It’s very simple: you are you and I am me.

Genta: Yes, that’s right.

Kojūrō: Kojūrō is Kojūrō. He is not Genta.

Genta (still baffled): As you say, sir.

Kojūrō: Genta, listen to me… Kojūrō is Kojūrō; Genta is Genta. Can we agree on that? “A retainer’s achievement is his master’s achievement.” Isn’t that odd?

Ironically, in a very few short minutes, there will be no difference at all between Kojūrō and Genta: they’ll both be lying on the ground side by side, equally dead. And it’s Kojūrō, not the haughty gang of samurai of the hostile clan, who bears ultimate responsibility for his servant’s unnecessary and gory demise. Kojūrō after all could have backed down, apologized and walked away from his foes, but his class pride wouldn’t ever have permitted him to do that. Thus, the young samurai is broad-minded enough to share a drink with those beneath him in the social hierarchy, but not broad-minded enough to protect the life of an “inferior” at the expense of his own “honor.”

This filmmaker’s employment of irony here rivals that of Buñuel in his best films. It’s so subtle, in fact, that it might well be misconstrued by the naïve viewer. It may appear, for example, that Uchida, in scenes like this one, is ridiculing the socialist idea of brotherhood, at least in the context of a society as rigid as feudal (or modern) Japan.

Actually, though, Uchida is affirming a key idea of Leftist theory: namely, that equality can’t be bestowed upon the powerless by those above them in the social order, but must be fought for by the oppressed themselves, in solidarity. And the fact that Gonpachi, Genta and female victims like Otane can’t even perceive themselves as oppressed, never mind make common cause to free themselves, renders their ultimate liberation impossible.

Craig Watts, in his seminal essay on Uchida, has pointed to this film as the key example of the director’s employment of Maoist theory – which he mastered during his stay in China – as an element in the dramatic structure of his films. Just as in real life (according to this theory) logical contradiction upon contradiction leads inevitably to a violent revolution, so the contradictions inherent in Uchida’s characters’ lives build upon each other, leading inevitably to explosive violence.2

(Continued on Page 4)

[…] A Bloody Spear at Mount Fuji (Chiyari Fuji; 血槍富士), 1955 […]

[…] Saloon (Tasogare Sakaba; たそがれ酒場), 1955A Bloody Spear at Mount Fuji (Chiyari Fuji; 血槍富士), 1955Police Officer (Keisatsukan, 警察官), 1933The Mad Fox (Koiya koi nasuna koi; […]

[…] four have received more than 200 votes on the Internet Movie Database: A Fugitive from the Past, A Bloody Spear on Mount Fuji, Hero of the Red-Light District and the first film in the five-part Miyamoto Musashi series.) I […]

[…] a very rough sketch for the neurotic young samurai Sakawa in Uchida’s first postwar masterpiece, A Bloody Spear at Mount Fuji (1955). But the tragic consciousness that Uchida brought to his depiction of that complex character […]

[…] Kikushima Ryūzō (book) and television film Dotanba (1956)1 […]

[…] after the Occupation to condemn or at least question feudal authority, as he did most famously in A Bloody Spear at Mt. Fuji (Chiyari Fuji, 1955), was working within an existing tradition rather than breaking with that […]

[…] suggest that the novice reader start with my review of Uchida’s classic comeback film from 1955: A Bloody Spear at Mt. Fuji, the very first review I composed for this […]