Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

(Continued from Page 1)

This film was Uchida Tomu’s most personal project of the postwar era. In the blog post for A Bloody Spear at Mt. Fuji, I described how that film, a remake of a 1927 silent movie by Uchida’s deceased friend Inoue Kintarō, literally fell into Uchida’s lap, as he inherited it from its originally-proposed director, Shimizu Hiroshi. This established a pattern for Uchida’s later postwar work, in which he often took on studio-assigned projects – most notably, the Musashi series of the 1960s – and managed to make them vehicles for his personal themes and obsessions, as well as, at times, occasions for visual experimentation. But A Fugitive from the Past, more than any of the others, was his film from the beginning, one he felt he had to make not just for his own artistic ambitions, but to help the industry that had made him a celebrated figure in Japan.

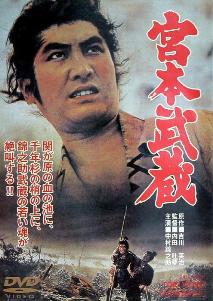

In my essay about the film, published in the booklet accompanying the 2022 Arrow Video Blu-ray release, I point out that, in the depressing commercial situation of the Japanese film world of 1964 – in which television set sales were soaring and cinema admissions were plummeting – Uchida had become obsessed with the idea that only by telling stories about modern Japan in a completely contemporary style could the industry save itself.1 This insight put Uchida in a somewhat awkward position, however, because he was at the time deeply immersed in finishing the five-part feudal epic Miyamoto Musashi, and had just recently completed and released the series’ penultimate installment. Thus, he fully recognized that he himself was, in a sense, “part of the problem.”

The filmmaker’s son, Uchida Yusaku – who collaborated closely with his father on the production of A Fugitive from the Past – remarked in a filmed interview that the Musashi series’ installments became somewhat less successful at the box-office over time. According to Yusaku, however, this was interpreted by his father as a sign not of a falling-off in audience interest in the Musashi narrative, but of the decline in the health and viability of the Japanese film industry in general, and he was desperate to reverse this trend.2

In a discussion with Toei’s management, Uchida had indicated his strong desire to make his next film a narrative set in contemporary Japan, rather than yet another jidai-geki film.3 At about the same time, according to Yusaku, his father went out for drinks with a local film critic, Izawa Jun of the mass-circulation national newspaper Asahi Shinbun (English: “Asahi News,” or “Rising Sun News”), and told Izawa much the same thing. The journalist then pointed out that his newspaper had serialized a fascinating modern detective novel, Kiga Kaikyō (The Hunger Straits), by the prize-winning author Mizukami Tsutomu (also known as Minakami Tsutomu), which had recently been published as a book. Izawa suggested that this work would make an excellent film, and even volunteered, to Uchida’s enthusiastic approval, to personally pitch a film version to Toei. And so Izawa went to the studio and convinced its management that they could make a wonderful adaptation of Kiga Kaikyō – if Uchida Tomu were assigned to direct it. Toei then contacted Uchida, who allowed himself to be “persuaded” to develop the project.4

Planning for the film was originally carried out by Okada Shigeru, the new head of Toei’s Tokyo studio (known as Tosatsu), who was very enthusiastic about the project. It was Okada who insisted that up-and-coming screenwriter Suzuki Naoyuki be assigned to write the script.5 From the beginning, Uchida wanted Mikuni Rentarō to play Inukai, but the otherwise strongly supportive Okada hated Mikuni and didn’t want him to be cast. However, Uchida threatened to quit the project if his choice was overruled, and so Okada backed down.6 7 Okada recommended for the role of Sugito Yae the acclaimed Toei actress Sakuma Yoshiko, whom Uchida at first accepted.8 9 But before production could be greenlighted, Okada was transferred back to Toei’s Kyoto studio (known as Kyosatsu) and another executive, Tsujino Kimiharu, replaced him.10 Uchida then recast the role of Yae with Hidari Sachiko,11 12 who had achieved acclaim, both domestically and internationally, for her performances in films by Imamura Shōhei (The Insect Woman (Nippon konchūki, 1963)) and her then-husband, Hani Susumu (She and He (Kanojo to kare, 1963).

Unlike Okada and Tsujino, the president of Toei, Ōkawa Hiroshi, was leery of the project from the beginning. His strategy for the company was to make low-budget movies as program pictures to be released as double features, and the proposed film didn’t seem to fit this plan. But the younger Uchida and an employee named Abe Seiji (who would later become a prominent television producer) managed to change Ōkawa’s mind by pretending that the film’s budget would be considerably lower than it eventually turned out to be.13 The sly deceptions that the Uchidas, both father and son, perpetrated to get this film off the ground demonstrate how significant the project was to the director.

Uchida also personally selected, for the crucial supporting role of Det. Ajimura, Takakura Ken,14 with whom he had already worked on The Outsiders (Mori to mizuumi no matsuri, 1958) and the Musashi series. The timing of this casting was fortuitous: only a few months after A Fugitive from the Past was released in January 1965, Takakura would finally become a superstar in Japan by playing an escaped convict in Abashiri Prison (Abashiri Bangaichi), the first in a highly successful series of chase thrillers directed by Ishii Teruo.

The most unexpected casting choice was that of the performer chosen for the role of the older police detective, Yumisaka. Actor Ban Junzaburō, who turned 57 just before the film was released, was already famous, but only as a comedian and singer; this was his first dramatic role.15 In the West, this choice would have been analogous to casting Jerry Lewis as Inspector Javert in a modern-dress version of Les Misérables.

On the set, conflict between the director and the actor arose immediately, and was never resolved. According to Uchida Yusaku, his father insisted on directing the highly experienced Ban, who had first worked with Uchida decades before in the prewar era,16 as if he were an untutored child performer, telling him in minute detail where to look and how to move. One day, Ban didn’t show up on the set, but his representative did, and this man told Uchida in no uncertain terms that he couldn’t continue to treat his client in such a disrespectful way. But such was the power film directors wielded in Japan at that time – and such was Uchida’s arrogance – that the filmmaker continued to direct the unfortunate actor in the same humiliating way, and Ban was forced to submit.17 As a result, Ban goes through the entire movie with a haggard, haunted look, which is, ironically, perfect for the tormented, obsessed character he plays.

Filming took place in the summer and autumn months of 1964, ending in early December. Location shooting took place in Tokyo; in the northernmost island of Japan, Hokkaidō; in the Shimokita peninsula at the northern tip of the main island, Honshu; and in the port city of Maizuru, the same port at which Uchida had arrived from China in October 1953, after his long self-exile there.18

In the essay I wrote for the Arrow Blu-ray booklet, I mentioned the history of the Toei W106 Method – a series of photographic effects that expressively exaggerates and distorts the filmed image – a technique that Uchida created specifically for this movie, and which adds so much to its dramatic impact.19 (We will discuss its use in detail in the section “Commentary and Analysis” below.) It should be noted that Uchida’s brother-in-law, cinematographer Midorikawa Michio, served as an official advisor on the use of the W106 Method, and helped Uchida develop the look of the film.20 Since Midorikawa had also been the cinematographer on Earth (Tsuchi) way back in 1939, he serves as an intriguing link between Uchida’s most acclaimed prewar classic and his most acclaimed postwar one.

The fate of this film follows the same distressing pattern we have seen repeatedly in Uchida’s career: the filmmaker fights to get his challenging vision onscreen, only to see his work mutilated, either by circumstances beyond his control (war, neglect) or the direct interference of the studio. Among his films that follow this pattern are Theater of Life: Youth Version (Jinsei gekijō: Seishun hen, 1936), of which about 60 percent survives; Unending Advance (Kagirinaki zenshin, 1937), of which about 80 percent survives, as the work was severely cut by Nikkatsu in the postwar era, and Earth (1939), of which the last reel is missing and the first reel is only available for viewing in a print at the National Film Archive of Japan (NFAJ) in Tokyo.

In the case of Fugitive, the story of its making is a particularly painful tale of a clueless studio disrespecting its most esteemed filmmaker in his sunset years. Uchida knew perfectly well that he needed at least three hours to tell this exceptionally complex story effectively, and his initial edit of the film was 192 minutes (3 hours, 12 minutes). However, by this time, Tsujino Kimiharu, Okada’s successor, who had been instrumental in budgeting and supervising the film, had been transferred to the main office, and a man named Imada Tomonori had taken his place.21

Imada, a pivotal figure for the studio, as he had helped create Toei Animation, had been born in 1923, that is, after the much-older Uchida had begun his career as a director. (He was 41, Uchida 66.) His job was to create films that could be programmed as double features for the theaters Toei controlled, and Uchida’s movie was way too long for this purpose, so Imada demanded that Uchida edit it down to what he thought would be a reasonable length. When the filmmaker balked, Imada ordered an assistant director named Ōta Kōji to cut the film according to his instructions.22 This must have been a particularly bitter blow for Uchida, because he had conceived of the movie in the first place as a means to help the industry, including his own studio, recover from its current slump.

Uchida threatened to take his name off the credits if his wishes were not respected. Soon, the private dispute was somehow leaked to the mainstream press, creating a public scandal for the studio. The main focus of the news story was the generational divide between the antagonists, Uchida and Imada.23 More than anything I’ve ever read, this incident attests to Uchida’s fame and prestige in Japan at the time.

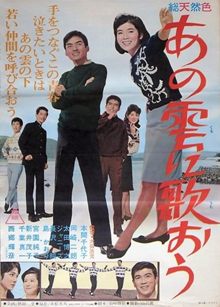

Through the intervention of the film’s original planner, Okada, a meeting was arranged between Uchida and the head of the company, Ōkawa Hiroshi, and a compromise reached. A 183-minute “restored” version of the film – still nine minutes shorter than the director’s original 192-minute cut, which, if it even still exists today, has apparently not been located – would premiere at a small number of urban theaters that Toei directly controlled. The rest of Japan would see a 167-minute version – that is, slightly over two-and-three-quarter-hours – on a double bill with, of all things, a teen musical called Let’s Sing to That Cloud (Ano kumo ni utaō, 1965), directed by Ōta Kōji, the same man who had cut Uchida’s film. This movie was created as a vehicle for the young female pop idol Honma Chiyoko and also featured future martial arts superstar Sonny Chiba (Chiba Shin’nichi) as, of all things, a high school English teacher.24 25

Following this incident, the fed-up Uchida, after a decade with Toei, severed his contract with the studio. However, when he, as a newly-freelancing director, eventually shopped around to the major companies his next project, an adaptation of Ozaki Shirō’s popular novel, Theater of Life (Jinsei gekijō) – he had filmed the very first adaptation of this book, for Nikkatsu, way back in 1936 – only Toei, the studio most strongly committed to the yakuza genre, was interested. The resulting film, Hishakaku and Kiratsune: A Tale of Two Yakuza (Jinsei gekijō: Hishakaku to Kiratsune), Uchida’s penultimate work, was released by Toei in 1968, finally ending the director’s rocky relationship with that company.26

Uchida had his revenge, posthumously, in the 1970s. When A Fugitive from the Past was re-released in 1975, only the 183-minute “restored” version was distributed, and in all subsequent re-releases, this is the only one that’s been shown in Japan. (However, as mentioned before, this version is still nine minutes shorter than the “director’s cut.”)27 28 Sympathy for Uchida’s highly-publicized frustrations with Toei may have gone some way toward influencing Japanese critics to select the film as among the Top Ten Japanese films of all time in both the 1995 and 1999 Kinema Junpo retrospective polls – an honor richly deserved.

A Fugitive from the Past is, historically-speaking, the most important movie Uchida Tomu ever made.29 It’s certainly the director’s most acclaimed work in Japan. Of all his postwar films, it ranked highest in the annual Kinema Junpo (KJ) poll at the time, appearing at fifth place for the very competitive year of 1964.30 More significantly, the film appeared in all three subsequent KJ Best-Japanese-Films-of-All-Time polls: in 1995 (thirty years after its release), it placed sixth among all Japanese movies ever released, and in 1999, its ranking rose to third place, higher than Ozu’s world-famous Tokyo Story (Tokyo monogatari, 1953). By 2009, its position had slipped to a still-impressive thirteenth place,31 tying with Kurosawa’s classic thriller High and Low (Tengoku to Jigoku, 1963, with which Uchida’s film is often compared) and ranked slightly higher than the greatest of Kobayashi Masaki’s masterpieces, Harakiri (Seppuku, 1962).32

It’s also the most surprising movie he ever made. Despite the director’s advanced age (he was 66-years-old when the film was released), it was completely up-to-date – thematically, stylistically and even technically – with the radical changes taking place in the national cinema of its day, and was avant-garde even by those standards. This was an astounding achievement for a man, not in the best of health, who had begun his career in the silent era. Furthermore, the film seems to me to fuse, to a greater degree than any other that Uchida directed, the “Realist” and “Expressionist” tendencies of his style. Thus, it’s a work whose look, tone and “feel” are totally different from anything its creator had previously made, and would make subsequently. It’s also probably his most personal film ever, as I will argue below.

However, online English-language reviews of the film are problematical, in that the writers, though they almost always praise the work, make significant mistakes, not just on the level of cultural misunderstanding, but in the interpretation of basic narrative information. For example, many if not most critics describe the protagonist, Inukai, as a ruthless criminal from the very beginning of the story, though a careful reading of the film demonstrates that this is simply not true. In addition, important ways in which the film’s narrative differs from that of the novel on which it is based – and the implications of these changes in terms of how Uchida wants the characters to be perceived – have generally not been taken into account, though this is excusable, given the novel’s obscurity outside Japan. (I haven’t read Mizukami’s book, which has never to my knowledge been published in English translation, but I’ve read descriptions of its plot by the scholar Yomota Inuhikō and others.)

These are not minor matters, but rather are crucial in interpreting Uchida’s complex intentions. To clarify those intentions, to provide historical context – both in regards to Japan’s national history and the history of its cinema – and to explain how and why the movie works as well as it does will be the main goals of this commentary.

The movie’s opening scenes, set in 1947, occur during a period that was, at the time of its release, very fresh in the minds of the adults in its audience: the humiliating squalor and chaos of the five years following the Japanese surrender that ended World War II. Of all the defeated powers, including Germany, Japan was the most totally defeated. For those knowledgeable in Japanese Cinema history, this early postwar era is familiar from works as diverse as Kurosawa’s pre-Rashomon “neorealist noir” crime movies – Drunken Angel (Yoidore tenshi, 1948) and Stray Dog (Nora inu, 1949) – Kinoshita Keisuke’s experimental A Japanese Tragedy (Nihon no higeki, 1953), and Imai Tadashi’s grim slice-of-life melodrama And Yet We Live (Dokkoi ikiteru, 1951).

All those earlier films, however, were made at the time those national events were occurring, and by moviemakers who were witnessing, and directly affected by, those events. Uchida’s film was made at a remove of two decades, by a filmmaker who had been abroad in China rather than in his native land during the crisis period depicted.33 Furthermore, Uchida was luckier than his filmmaking peers in that he didn’t need to concern himself with the U.S. Occupation’s censorship, which formally ended when the Occupation was terminated in late 1952, so he could be much bolder in 1964 than those other directors dared be in the 1940s and early 1950s.

The movie begins in September 1947 – approximately two years after the surrender – with footage of a storm-tossed sea in the Tsugaru Strait, accompanied by a prologue narration. These opening scenes on the island of Hokkaidō in the north of Japan show the effects of a typhoon that devastated those communities closest to the strait. The monster storm (which had actually occurred in 1954: see the Synopsis above and accompanying endnote) is presented by Uchida as a metaphor for the upheaval of the entire social order in the wake of Japan’s defeat.

An atmosphere of moral chaos is thus skillfully established, in which the two convicts, in the general confusion, can brazenly murder the husband-and-wife pawnbrokers, the Sasadas, and then set fire to their house, fully expecting to get away with their crime. (Among the many beautifully subtle details in this film: at the end of the brief spoken prologue, after the narrator utters the words, “The unexpected track of the typhoon caused a lot of damage,” the film cuts from a shot of the waves on the stormy coast to a shot of the Sasadas’ house on fire, so that the rising of the white sea spray in the first shot “matches” the billowing white smoke from the burning house in the second shot.)34 Almost every location we see in the film appears ruined, blandly featureless or vaguely dilapidated. Black-and-white cinematography is perfectly appropriate for this film because unlike, say, the world of Hero of the Red–Light District, the sordid reality of the social order is never concealed beneath a prettified surface, but is clearly visible to all.

At the train station at which the destitute protagonist, Inukai, is shown waiting for his two companions, both of whom are recently-released ex-convicts, the people in the crowd huddle together like refugees from a battlefield. Inukai, however dire his circumstances, is clearly only a notch or two lower in status than the general population in this desperate postwar world. No one standing near him seems to regard his shabby appearance as threatening or even unusual.

The sense of chaos applies even to the big city, Tokyo, where Yae goes to make a new life for herself after giving up prostitution, only to find that living as an “honest woman” in a city full of youth gangs, streetwalkers and other outcasts is much tougher than she had imagined. Power outages are frequent, angry protesters are out in force on the streets and the black market is ubiquitous. Yumasaka’s wife actually berates him for forbidding her from buying food on the black market, because their two sons are thus constantly hungry.

But, of course, Uchida is not seeking to capture just the look of early postwar Japan, nor only the nature of mere sociological phenomena like the black market, but the moral mood of a defeated people. As Alyssa Pearl Fusek has written about this era, “The low morale and despair of the Japanese people was so prevalent and widespread that it warranted a name — kyodatsu jōtai, a ‘state of lethargy’ or ‘mental numbness.’ It was a breeding ground ripe for escapism and counterculture development. The Occupation provided the fuel, and counterculture writers sparked the fire in what became known as kasutori culture, kasutori being the name of a particularly heady alcohol.”

The only cinematic vision I’ve seen of the physical and moral degradation of this era that’s as comprehensive as this film is Naruse Mikio’s masterpiece Floating Clouds (Ukigumo, 1955), and even that narrative is presented in the context of a love story. But isn’t this film, too, a love story of sorts? After all, Inukai and Yae, who seem irresistibly drawn to each other, have much in common… as we shall demonstrate below.

The narrative of this film involves a wider range of locations than any other extant Uchida movie. Below are the significant places that are either featured in the narrative or mentioned by name by the characters. Notice that there is a general southward motion of the two main characters, Inukai and Yae, in the course of the narrative, followed by an abrupt return to the north of Japan at the very end.

Okanbayashi – Inukai’s birthplace in Kyoto prefecture, a (presumably fictitious) village near the city of Kyoto; he is later known there as the wealthy philanthropist Tarumi and greatly admired by the residents for his many public works.

Osaka – The city where Inukai claims to have lived for a time following primary school.

Kutchan – The capital of Shiribeshi subprefecture in Hokkaidō, the location of Inukai’s failed farm, Samejima, after he had moved to Hokkaidō in 1940 during the war with China.

Sapporo – The largest city and capital of Hokkaidō, where Inukai worked with the two ex-convicts in the mines in 1947 shortly before the beginning of the narrative.

Asahi – A town in Kamikawa subprefecture in Hokkaidō, where Inukai stays at a spa with the ex-convicts on the night before the murders (in September 1947). This is also where the convicts first meet Mr. Sasada, which gives them the idea to rob him.

Iwanai – The town in Hokkaidō where the murdered pawnbrokers, the Sasadas, were living and the setting where the narrative begins. This place also contains a train station at which Inukai waits for the ex-convicts to join him.

Hakodate – A city in Oshima subprefecture in Hokkaidō, the third largest city on the island, located across the strait from the city of Aomori on the main island, Honshu. This is the destination of Inukai and the ex-convicts before their train is stopped. It’s also the home base of Inspector Yumisaka.

Shimokita – A peninsula in Northern Japan, located in Aomori Prefecture in the Tōhoku region at the extreme northern end of the largest Japanese island, Honshu. This is Yae’s home region. It is also where Inukai burns the stolen boat and encounters the itako during the séance.

Ōminato – A town (now known as Mutsu) located in Shimokita peninsula in Aomori Prefecture. Yae lives here at the beginning of the narrative, when she sleeps with Inukai at the brothel, Hanaya House, after he had crossed the strait in the stolen boat.

Mt. Osore or Osorezan (Mount Dread) – The famous, real-life mystical mountain that Yae and Inukai observe from her window in Ōminato and which is also alluded to again at the end when Inukai, a prisoner, is crossing by ferry from Honshu back to Hokkaidō. This mountain may be considered the locus capitis (capital site) of the film.

Yunokawa – The site of a well-known hot springs (onsen), near Hakodate in Hokkaidō, where Yae goes for a few days with her father after Inukai gives her a large sum of money. It is here that she is found and questioned by Yumisaka.

Kamedo (or Kameido) – A district in Kōtō Ward (Kōtō City) in Tokyo, where Yae moves after her encounter with Inukai. She works for a bar to drum up business by accosting potential customers in the street, but she encounters many threatening yakuza before her employer is arrested and she runs away.

Maizuru – Tarumi’s residence in 1957, a hot, humid town on Maizuru Bay in western Kyoto Prefecture, accessible from Hokkaidō by the Sea of Japan. This is where he kills Yae and his own male secretary, Takenaka. Thus, Inukai/Tarumi, now a murderer, is back in the Kansai region, where he started out.

One of the most important articles in English about the film – indeed, one of the few scholarly articles published in English about it – discusses the work in terms of “fractured landscapes” (italics mine). The author, Alastair Phillips, argues that a sense of the geography traversed by the three main characters – Inukai, Yae and Yumisaka – as well as an understanding of the way the contrasting locations are presented cinematically, are crucial factors in any coherent interpretation of the film.35

This geography is often presented symbolically, and sometimes even anti-realistically. For example, the scenes on Hokkaidō, far from the urban centers of Tokyo, Kyoto and Osaka, symbolize the poverty and loss experienced by many Japanese in the early postwar period. This poverty is personified by Inukai himself, who is identified in the audience’s mind with the northernmost Japanese island, though, as already noted, he was neither born nor raised there. By contrast, the scenes in which Inukai wanders in rags through the Shimokita peninsula in the volcanic region of Mount Osore – an action that takes place soon after he kills the murderous convicts and burns the stolen boat – are deliberately filmed to resemble a hellscape, including shots of steam rising from the ground.

These locations, as Phillips points out, often possess a temporal significance as well. The vicinity of Mount Osore is an ancient space, “a link between the cultural forms of the past and present,” and the figure of the itako – the female spirit medium – that Inukai comes upon by accident, offers a “ghostly continuity between the dead and the living” through her shamanistic ritual.36

Referring to Uchida’s frequent use of one aspect of the W106 technique, in which he changes, without warning, the filmic image from positive to quasi-negative (called the Sabatier effect: see below), such as in the scene with the blind itako, Phillips notes, “Uchida is here disrupting a sense of seamless continuity between the past and present in order to convey a temporally defined consideration of the cost of social transformation for mainstream Japanese culture. The film is looking back at a set of recent pasts that relate powerfully to the immediate present.”37

The “immediate present” to which Phillips is referring – that is, Japan in early 1965, the time of the film’s release, more than seven years after the point (the summer of 1957) at which the narrative concludes – was the aftermath of the triumphant 1964 Tokyo Olympics. That event, as he writes, had been intended to display to the world “Japan’s monumental economic recovery from the trauma of World War II.”38

Thus, Uchida’s intent was a subversive one. Whereas the Japanese government had wished, with the Olympic Games, to present an image of Japan as an orderly, seamless, unified entity which had expunged any remaining traces of its wartime ordeal, Uchida conveyed, partly through the use of landscapes, his country’s fissures and fractures. These included the gap between the rich urban south and the poor rural north, as well as the nation’s uneradicated links to the war, to the Occupation period and to its “primitive” ancient past… all in the context of a work fitting neatly within the already long-established detective film genre.

(Continued on Page 3)

[…] Japanonfilm blogger appears to see A Fugitive from the Past, in its focus on social issues, as an outlier among Uchida’s postwar films. I would argue the […]