Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

(Continued from Page 3)

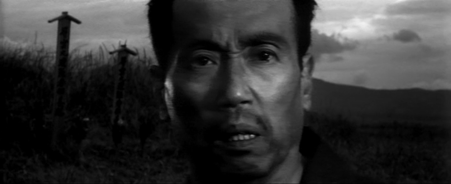

In Japanese Cinema during the two decades after the war, there were many prominently featured characters who were depicted as prostitutes, as well as, of course, numerous depictions of women in the “water trade” – geisha, barmaids, etc., operating at the margins, so to speak, of sex work. But it’s unlikely that any such character was ever as strange and fascinating as Sugito Yae, the frighteningly innocent hooker played by Hidari Sachiko in this film. The temptation for the viewer is to see her as mentally-challenged or semi-deranged, and in fact she seems literally to go mad when she glimpses the shattered right thumb that reveals Tarumi to be Inukai. But this simplification would be to ignore both the complexity of the character and the ways in which she is representative of a larger societal breakdown.

She comes from Shimokita, which, as Nakanishi points out, had a large community of burakumin, so she is almost certainly one herself. As a prostitute, she belongs to a profession identified with that outcast class. We are told by Yae’s father that she went to Ōminato with the hope of finding an honest job, but had drifted instead into sex work. Of course, many Japanese women of the time who were not burakumin found themselves in the same predicament. (When Yumisaka goes to Tokyo to track down Yae after realizing she’d lied to him during his original questioning, he’s told by the police there that finding a particular prostitute in the capital would be like searching for a needle in a haystack.) So at the point in time at which she meets Inukai, her prospects of escaping her lot in life seem bleak indeed.

We first see Yae at the strange seance for her mother, presided over by the spirit medium (itako), in the cabin at Shimokita, which Inukai spies upon. Although we never quite see her face, Yae, by her body language, shows every sign of believing in what is happening. Yet later, alone with Inukai at the brothel Hanaya House, she ridicules the itako, imitating her frightening cries. (“There’s no way back!”)

Yae is already half in love with this odd man whom she has taken in like a stray dog. Yet she’s completely oblivious to the fact that she’s upsetting him with her mocking allusions to death and hell, which Inukai takes very seriously indeed. This sequence must be one of the strangest sex scenes ever filmed, one in which Uchida was not, of course, permitted to display any nudity, but nevertheless managed to convey the sadomasochistic basis of the relationship between the two people.

A most reluctant client of Yae, Inukai seems driven not so much by lust than by the need for companionship and shelter. Yae, in turn, is driven by a peculiar combination of maternal tenderness and infantile fascination. She clips his fingernails like a mother, but giggles like a child at his fear of storms and spirits, a fear rooted, of course, in the trauma caused by the horrifying events he experienced during the typhoon – events of which she is, and will forever remain, completely ignorant.

The scene of the morning after Inukai’s tryst with Yae is intriguing. While he is still sleeping, she examines her face in the mirror and the deep scratch marks that appear on her neck, which look like they were made by some wild beast. In this way, without words, Uchida shows that she has completely fallen in love. There’s a related shot in Uchida’s Chikamatsu’s Love in Osaka, in which we see the prostitute Umegawa, who has fallen for the clerk Chubei, glancing at herself in the mirror in a similar fashion.

After he departs, leaving behind the enormous tip, Inukai becomes a fetish object for Yae, almost like a Buddhist deity. Even the money itself – other than the fraction of it that she had given her family to help them get out of debt, or had used herself to finance her move to Tokyo – becomes fetishized, and remains hoarded, unspent.

It’s very interesting that Inukai and Yae have such completely different attitudes toward the money that has so improbably come their way. From Inukai’s point-of-view, his unexpected windfall is capital, to be invested in founding his highly successful starch-processing company in Maizuru. This mindset corresponds to the Marxist concept of exchange value: the money is of worth only in its ability to purchase the materials and manpower to jump-start his capitalist enterprise, so he can leave behind forever his Inukai identity. For Yae, the remaining cash, after her necessary expenditures noted above, has only what Marxists call use value, in the same way the fingernail has: as a memento of Inukai, to be preserved at all costs.

Despite her (relative) wealth, therefore, she is so determined not to spend Inukai’s cash that at one point she’s in serious danger of being cast out, homeless, onto the mean streets of Tokyo, until the kindly Motojima couple rescues her.1 2 In a paradoxical sense, though, her obsession with Inukai is the opposite of love. Her worship of him is almost completely disconnected from his identity as a human being, as in truth he is neither a devil nor a saint.

Both Yae and Inspector Yumisaka develop a fixation on this strange man because of their need to distort reality. For Yumisaka, the capture of the “monster” Inukai would restore, he thinks, some sort of moral balance to the world, which is why he’s so driven to solve the case. For Yae, some sign of recognition from Inukai/Tarumi, however slight, would give meaning to a life tragically wasted in sex work. (It should be noted that Yae, in their final confrontation, never asks the married Tarumi to become romantically involved with her or even to have sex with her again.) And the resolution of their respective obsessions brings neither the prostitute nor the detective happiness: Yae is rewarded for her masochistic devotion by being brutally murdered, and Yumisaka, in the end, is as baffled and frustrated as ever, because Inukai cheats the State by carrying out the death sentence… on himself.

I think one could make a very strong case that the middle section of this film, that is, Act Two of the film’s three-act structure – roughly corresponding to the second hour, which focuses mostly on Yae, and in which the protagonist, Inukai, is almost entirely absent from the narrative – is the absolute masterpiece of Uchida’s career.3 The director’s skill in these scenes in creating and maintaining a complex atmosphere of tension and dread, in which an entire chaotic society is laid bare and dissected like a laboratory animal, is worthy of Kurosawa at his best. Although the first third of the film, Act One, has many strong sequences, and though Act Three contains the remarkable scenes of Inukai’s interrogation, and the even more remarkable final scene, I would maintain that Act Two, culminating in the murder of Yae, is the most consistently brilliant in the film.

We will begin with the scene in which Yae is depicted on the streets of the Kamedo district of Tokyo, trying to drum up business for the bar for which she now works… and, because of her timidity and fear, she’s not doing too well. She stands in the midst of a gaudy crowd made up of day laborers, pan pan girls (young street prostitutes) and the American soldiers they are servicing. It’s an unusually cluttered shot for Uchida, sufficiently stylized to suggest an image of the Occupation period as rendered through the exaggerations of memory, rather than by the standards of documentary realism that apply to other parts of the film.

Out of an alleyway, a large group of prostitutes, running from a police raid, suddenly appears, and Yae, caught up in the commotion, runs with them, seeming to forget that she’s no longer engaged in sex work. In a famous overhead crane shot, we follow Yae over a footbridge, then to an advertising kiosk behind which she temporarily takes refuge, then rushing in panic through the streets past tacky, flimsy-looking shops, where she’s momentarily manhandled by a soldier, and then finally running breathless into the bar of her employer… who ridicules Yae for her fears, as such police raids are an everyday occurrence in Kamedo.

As opposed to the location scenes that appear earlier in the film – those which take place on the beach at Hakodate, for example – this entire sequence was obviously shot on a very elaborate studio set. This was done primarily, one assumes, for perfectly practical reasons, as it is always easier to execute such a complex and difficult crane shot in the controlled environment of the studio. But the studio-bound nature of the scene also has the effect of creating a sharp and deliberate visual break from the earlier scenes shot on location.

Alastair Phillips discusses the implications of this short sequence in the following passage:

In an introductory studio-based long take, for example, a teeming street scene clearly evokes the troubled hybridity of the era as US soldiers, impoverished shopkeepers and returning war veterans from Japan’s lost empire are interlinked by Uchida and his cinematographer Nakazawa Hanjirō’s continuously roving camera. Here, for example, there is no static gaze, no invitation to peruse and examine the defining contours of the landscape… Camera movement is broadly subordinate to the motivational movement of the human figure [that is, Yae’s]. Space is determinedly congested, fluid and chaotic.

Phillips, op. cit., p. 226

Elsewhere in the article, Phillips, referring to the visual contrast between the northern Japanese and Tokyo settings of the film, states, “It is not so much that the rural landscapes of the Shimokita Peninsula are perceived as a world away from the urban landscapes of Tokyo, but that within the ideological schema of the film both spaces are haunted by an interconnected and ongoing history that remains to be actively detected [emphases mine].”4

So the viewer’s main task of detection in this piece of detective fiction doesn’t involve figuring out who the criminal is, as his identity is known from the outset. It involves perceiving, through Uchida’s presentation of the various settings, the reality of Japan’s history and how this history helps bring about the narrative’s tragic conclusion. This is a haunted movie – even a horror movie (see “Which Genre Is This Movie, Anyway?” below) – in that the two main characters, both fugitives from their respective pasts, can’t escape that terrifying history despite their constant struggles to do so. In Yae’s case, the shadow of sex work – her “heritage,” so to speak, as a burakumin – can’t be elided merely by moving to Tokyo and getting an “honest” job, as the shot of Yae with the prostitutes on the footbridge conveys visually.

In a later scene, Yae returns to Kamedo in the evening, after attempting unsuccessfully to visit her friend Tokiko – Yae had spotted Yumisaka staking out the area around Tokiko’s house – just in time to witness an epic turf war by the local yakuza gangs in front of the bar where she works. The viewer sees her react, startled, to the sound of breaking glass. She then takes refuge behind a partition where, terrified, she witnesses a couple of thugs, including the tall, sinister yakuza Machida, beating up a member of a rival gang. The effect of Uchida’s composition, in which Yae behind the partition is situated on one side of the frame and the battling yakuza are on the other, makes it almost seem as if she’s watching the fight in a movie.

Finally, the police arrive and arrest the thugs. Yae moves to the other side of the partition in time to witness an officer arrest her frightened boss (presumably because she is needed as a witness), after the latter admits that her waitress never arrived for work. Before he departs, the cop remarks that he’ll come back to arrest the waitress (that is, Yae) as well. The latter then runs away, never to return.

Stills can’t adequately convey either the scene’s frenetic violence, or the amazing control with which Uchida blocks and frames the action. In addition to the sequence’s plot function – motivating Yae’s abandonment of her job and return to prostitution – it conveys more powerfully than any other Japanese film I’ve seen, even Drunken Angel or Stray Dog, the wages of war for that country during its immediate aftermath, in that the defeat unleashed social chaos not seen in the nation, perhaps, for centuries.5 The sheer dynamism of the movements of crowds and gangs is offset by a carefully planned mise en scene in which no shot, and no part of any shot, seems superfluous or wasted.

As has been pointed out by several commentators, including Yomota Inuhikō,6 the seaport city of Maizuru, in which Yae is reunited with Inukai for the last time, was the setting of Uchida’s repatriation in October 1953, after his long sojourn in China. Thus, there was for Uchida a personal as well as a plot significance to the fact that the climax of Act Two of the film takes place there.

When Yae arrives at the train station in search of Inukai, she is wearing a modest dress and a beehive hairdo, looking like a young middle-class wife. The poignancy of this did not strike me until I had seen the film several times: not only does Yae want to look her best for Inukai, but she also wishes, perhaps, to deceive him into believing that she’s given up sex work. She walks through the streets of the city, carrying her parasol against the hot sun, passing soldiers who barely give her a glance, as her attire and demeanor announce her (pretended) status as a “respectable” woman. But there’s a detail heard on the soundtrack that will prove ominous: the sound of crickets, whose noise, we’ll later discover, signals an oncoming thunderstorm.

After having been let into Tarumi’s house by his cold, haughty wife (played by Kazami Akiko, who had portrayed the innocent Otsugi in Earth a quarter-century earlier), Yae waits uneasily in the drawing room. We then see Tarumi from the back (a brilliant touch) as he walks down the stairs, so that the viewer is unsure for a moment if this man is really Inukai. When we do see his face, with his suave mustache, neatly-combed hair and dark-framed glasses, it’s difficult to see in this prosperous, handsome man the desperate, filthy tramp that he had been just ten years prior.

As Yae relates her story to him, Tarumi fidgets in his chair, alternating between looks of mild interest or amusement and feigned boredom. Yet we can sense the volcanic emotions beneath the man’s surface calm. There’s the slightest hint that, deep down, he yearns to reveal his identity to this woman to whom his single act of impulsive generosity had meant so much. At any rate, it’s obvious that he has no intention, at this point, of harming her.

When Tarumi lies and tells her there’s no connection between himself and this man Inukai that she is seeking, Yae – not knowing, of course, of the terrible crimes with which he had been involved – assumes he’s rejecting her merely because she is a prostitute. She breaks down, and in a heartbreaking scene, relates how “in my job, my body remembers the men touched by it, and a man that I madly embraced, I could never forget a man like him.” Because he won’t acknowledge her, she adds “I’ve lost all meaning in my life.”

It’s then that Tarumi makes a fatal blunder. Instead of contriving a way to politely but firmly get rid of his unwanted guest as soon as possible, he summons his secretary, Takenaka, and asks the young man to prepare tea for them. (Mrs. Tarumi, he’s told, had just gone out shopping.) Takenaka is puzzled by the presence of the strange, crying woman, but leaves the room to make the tea. Tarumi thus turns what ought to have been the briefest of visits into a protracted social call. The bourgeois manners he had no doubt acquired in his rise from pauper to tycoon ultimately serve as an important factor in his downfall.

As Tarumi waits anxiously for her to stop crying, the “song” of the crickets outside the window becomes louder, the room visibly darkens and the first peal of thunder is heard as the storm finally approaches. Tarumi, after a long silence, praises Yae for her “pure heart” and her “sincerity,” and this stops her tears. He requests that she come back someday to visit. Yae, embarrassed, apologizes and prepares to leave. Irrationally, Tarumi begs her to stay for tea.

At that moment, the clouds break. Tarumi – who, as we saw in Act One, hates thunderstorms – gets up to close the window, but in doing so, inadvertently reveals the damaged thumb of his right hand. Yae instantly recognizes the deformity, and ecstatically greets Tarumi as her hero, Inukai.

The shot in which this recognition occurs looks like a fast reverse zoom of Yae’s astonished face: very unusual filmic punctuation for Uchida. As she rushes forward and kisses Tarumi’s thumb, the Sabatier method (see below) is employed, so that the image appears to go negative, like undeveloped film. As the image returns to normal, she literally goes wild, jumping in front of him and screaming insanely as he tries in vain to evade her, echoing the scene at Hanaya House in which she giddily taunted him with the prophetic warnings of the blind itako.

Crying out, “My name is Tarumi; I am not Inukai” (which is probably the literal truth), he is attacked by her, until he puts his hand over her mouth to stop her cries, and they embrace. Almost imperceptibly, his hand moves downward to her neck. They slowly turn until Tarumi’s massive body totally obscures the woman from the viewer, except for her arms and hands, which clutch the top of his kimono.

The image goes negative again, as he lets out a harsh, guttural cry and she emits a choking noise. (However, the image is not really completely negative: note that Yae’s arms register on the image as light rather than dark, as they would be in a photographic negative.) Then there’s a snapping sound, as if Tarumi had torn the life out of her body, and she falls limp in his arms, to his astonishment. This murder is weirdly eroticized: it more closely resembles a rape than a killing.

He drags her into an alcove obscured by a screen. Before she breathes her last breath, she seems to smile at him. He emits a sound like an animal grieving.

Takenaka then enters with the tea tray and sees the lifeless body of Yae. Because Tarumi is, at that moment, completely turned away from him, the young man, had he kept his head, could have silently left the room unnoticed, put down the tray, and run outside in search of the police. Instead, startled, he drops the tray, alerting Tarumi to his presence. The unlucky Takenaka turns to run, but his much larger employer seizes his neck from behind and easily breaks it… as the image goes negative a third time.

It has occurred to me that this scene strongly resembles the sequence in the final part of the Sword in the Moonlight trilogy in which the mad swordsman/serial killer, Ryūnosuke, murders the innocent servant girl in cold blood. In each case, the killer seems suddenly to be seized by an irresistible urge to destroy his prey. The difference is that Inukai, unlike Ryūnosuke, feels genuine remorse for what he’s done… but not to the point of being willing to go to prison for it.

(Continued on Page 5)

[…] Japanonfilm blogger appears to see A Fugitive from the Past, in its focus on social issues, as an outlier among Uchida’s postwar films. I would argue the […]