Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

(Continued from page 2)

The more often I watch this movie, the more I understand that Uchida did not intend Otsuru to be seen as a conventional villainess. As has been pointed out by others (for example, here), in her grasping, amoral quest to attain her goals, she could well have served as the ironic heroine of one of Imamura’s 1960s films, such as The Insect Woman (Nippon konchūki, 1963), released only three years after Uchida’s film. But in Imamura’s work, the director totally rejected middle-class morality, something Uchida wouldn’t – or couldn’t – quite do.

Nevertheless, Otsuru has much more in common with the man whose life she destroys than is usually acknowledged. They are fatally connected, rather like Tetsuo the bankrobber and Itami the cop in Uchida’s Police Officer (Keisatsukan, 1933), except that, in this case, neither character really represents the established order. Both are “monsters,” fulfilling roles deemed necessary within society – merchant, whore – yet, for very different reasons, they know they will never be accepted by that society. Both have a “mentor” to instruct them in the ways of Yoshiwara: the merchant Echigoya in Jirō’s case, Hyogoya the brothel boss in Otsuru’s. Both are obsessed with money, and both see marriage as the solution to their problems, though again for utterly different reasons.

Could they have ever lived “happily ever after”? It’s an intriguing thought. When Jirō accuses her of being a liar, Otsuru insists, correctly, that she didn’t lie, because she would gladly have gone ahead and married the silk merchant if he hadn’t gone broke. The one fatal obstacle to a happy union – in which Jirō might have continued to live in a fool’s paradise and Otsuru, who is incapable of real love, might have served him as the “perfect wife” – is the bottomless greed of her employers.

A key scene in the film for our understanding of Otsuru is one that is not strictly necessary in terms of plot. She and her co-workers witness the funeral of a courtesan from a rival house, and they realize that, though the woman was popular with customers – at least before she got sick, probably from syphilis – she will be buried without a single customer, family member or friend to mourn or pray for her. (This is, by the way, historically accurate: most courtesans of the time were buried ignominiously in common graves.)

It’s here that Otsuru’s motivation becomes clear. She’s driven not by greed, per se, but by a perfectly understandable desire to transcend the grim futility of the courtesan’s fate. In her world, attainment of the status of tayū and marriage to a respectable customer are the only criteria of “success,” and she’s determined to achieve them by any means necessary. So the identity of the man she will marry is utterly unimportant.

These two seemingly opposite but actually quite similar characters – Jirō and Otsuru – initially bound by his illusory love, are then bound forever by his unquenchable hatred.

The violent, terrifying ending of this film has been justly celebrated (by, among others, film scholar Alexander Jacoby1) as one of the greatest action scenes in Japanese film history. A fact that’s often overlooked, however, is that the power of those last eight-and-a-half minutes – their extraordinary ability to evoke the classic tragic emotions of pity and terror in the viewer – derives not merely from Uchida’s masterly staging, but from the emotional intensity of the film’s previous ninety-some minutes. If the spectator had not become emotionally invested in this story and these characters, had not been swept away by Uchida’s cinematic vision of a lost era, that final scene would be just another competently-filmed swordfight.

In my original brief review of the movie on the World Cinema Paradise website (now sadly defunct), I pointed out how much I usually dislike what I call “one-man army” scenes in Japanese films, in which a single samurai absurdly defeats what appears to be a whole town full of adversaries, almost without breaking a sweat. But this climactic scene is a thrilling exception to the hoary cliché, because Jirō’s brilliance as a swordfighter – his “heroism” – is eerily plausible, given the volcanic rage that had lain dormant within him from long before the day he first met Otsuru. All his life, he had feared being regarded as a monster for his facial “deformity.” Now totally ruined and publicly branded a monster (and a fool to boot), everything Jirō ever had to lose has been stripped from him. It’s as if he were saying, “You call me a monster: good! I’ll show you how dreadful a monster can be!”

At the risk of stressing the obvious, please note that the following description of the film’s climax can only vaguely approximate its power. Only the experience of watching the film itself can reveal its full impact.

The scene begins with Otsuru setting forth on her public “coronation” as tayū – for she is now truly the “queen” of Yoshiwara. As she steps into the koma-geta platform sandals she will wear for the occasion, the courtesan Yaegaki, one of those whom Otsuru has supplanted, asks her, in a heartbroken voice, a strange question that serves as a kind of curse: “Courtesan Tamazuru, you have become the fair flower of Yoshiwara. Are you satisfied?” Completely ignoring her enemy, the very satisfied Otsuru, in her enormous, heavy costume, proceeds down the main street of Yoshiwara, flanked by the brothel guards and followed by her employers, Oken and Hyogoya. Everything about her costume suggests oppression, but she experiences the moment as her liberation, the fulfillment of her dream of revenge.

The rhythm of Nakamura Toshio’s brilliant music perfectly matches the pace at which the parade progresses; it’s almost as if the characters can hear the music, and it’s not impossible that the music was played for the actors as they filmed the shot without sound, as was once customarily done in silent cinema. The march of the characters is punctuated by a repeated harsh, metallic sound, like a sword being hurriedly removed from its sheath. There then follows a lovely long shot, taken from above, of the main avenue of Yoshiwara, with the procession flanked by onlookers and with blooming cherry trees visible in the background.

We then see the procession from ground level. But Uchida soon focuses on a strange detail: two red-clad children, girl courtesans in training, who look to be only about nine- and seven-years-old, the former carrying a box, the latter holding some sort of scroll. Such girls in Yoshiwara brothels didn’t have sex with clients, but they learned from their much older “sisters” what would one day be required of them, including how to deceive customers. So though still virgins, these little girls are already in the process of being corrupted.

In the real-life licensed quarters, there were many such children, some as young as six, all of whom had literally been sold into this grim world by their poverty-stricken parents.2 Such young girls also appear in, for example, Itō Daisuke’s 1951 film Five Men From Edo (Oedo go-nin otoko), which is set partially within Yoshiwara, but Uchida, in this film and in his previous work, Chikamatsu’s Love in Osaka, stresses their presence much more emphatically and disturbingly.

There follow two close shots. The first focuses on Oken and Hyogoya: he seems uncharacteristically distracted, while she gives an amusing little smile of smug self-satisfaction. Then we see Otsuru herself, whose face has hardened into a grimace of triumph, having defeated the “real” courtesans. Jirō is probably the very last thing on her mind at this moment.

The scene shifts to a trio of spectators, who serve as a kind of impromptu Greek chorus as they watch the approaching procession: the merchant Jōsuke; his friend, presumably another merchant; and the courtesan Iwahashi. They discuss the bizarre turn of events that has led a mere convict, Otsuru, to become tayū, the flower of Yoshiwara. Iwahashi sympathetically mentions Jirō in passing and they speculate about how he might feel if he were here to witness this event.

We then observe a hidden bystander in a sedge hat overhearing this conversation – Jirō himself.3 Jōsuke’s friend notes that the silk merchant alone paid the enormous costs of Otsuru’s promotion. Jōsuke is astonished and outraged that Hyogoya, that “worst of scoundrels,” paid nothing, while his friend is amused that Jirō was such an idiot. Jirō suddenly realizes the full extent of his folly.

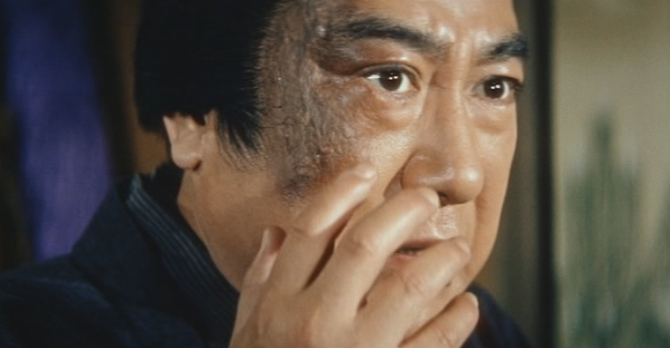

Jōsuke’s friend laughingly refers to the silk merchant as a “monster.” Brilliantly, it is only at that moment that Uchida allows us to see clearly Jirō’s face beneath his hat and to fully view his fatally-stained right cheek: the sign and symbol of his “monstrousness.” Then we see again Otsuru’s hard, loveless face, followed by the faces of Hyogoya and Oken.

The silk merchant suddenly lunges forward, shouldering his way through the crowd to block the parade. Some bodyguards try to stop him, but can’t restrain him. Jirō removes his sedge hat to reveal his identity. The outraged (and frightened) brothel keepers rush forward to remonstrate with him, but he responds by shouting that they had “betrayed” him – and by unsheathing the cursed sword.

The women in the crowd scream. Oken seems paralyzed by terror and Jirō, brandishing his sword, easily kills her. Hyogoya feebly tries to attack him, but after a life of leisure and luxury, the fat brothel owner is no match for the crazed silk merchant. Earlier, Hyogoya had gleefully compared Jirō to a pig that must be bled dry, but it is Hyogoya who’s slaughtered like a pig… by Jirō. As Otsuru and her entourage run for their lives, the crowd flees in all directions in panic.

Jirō chases Otsuru and, because her high geta sandals make walking, never mind running, difficult, he nearly catches up with her. But she, ironically, just manages to evade him by pushing the padded front part of her uchikake (as I believe it’s called) towards him, so that he winds up grasping, rather than the woman, her discarded clothing.

Meanwhile, one bodyguard after another falls under the silk merchant’s sword. Immediately after several dozen armed police from outside, in response to the emergency, have entered Yoshiwara, an officer gives a signal to two men to shut and bolt the gates to the pleasure quarter, so that curious bystanders cannot enter and the killer can’t get out. Ironically, this also blocks Otsuru’s only means of escape.

The warning bell sounds loudly, over and over. It’s at this point that Nakamura’s music becomes truly inspired. The steady sound of the bell mingles with bongos and what sounds like a samisen being played like a banjo, and punctuated intermittently by what sounds like the strings of a piano being strummed in a glissando, like a harp. The percussive effect of this music is visceral and overwhelming, perfectly complementing the visual chaos we see. (An entire article could easily be written about Nakamura’s score alone.)

The camera shifts to a view from above, as Jirō repeatedly and clumsily lurches with his sword towards Otsuru, who has by now removed her geta sandals, making it finally possible for her to run, and who again and again narrowly escapes him. We are then shown a weird close-up of Jirō, who spots Otsuru in the near distance, and the smiling expression on his face shows that he is clearly insane, rather than merely enraged. (“Wait, wait,” he cries dementedly, as if she would willingly wait for him to catch up to and kill her.)

There is then what looks like a moving hand-held shot as Jirō approaches the courtesan. Because of the armed guards between them, he doesn’t quite reach his quarry, but he does grab her obi – the sash around the midsection worn with a kimono – and literally unwinds her, so that she twirls and falls to the ground. The courtesan, having lost several important elements of her costume, has been divested by the silk merchant of her Tamazuru identity, reverting to the mere convict she once was.

As she crawls on the ground, Jirō stops her by stepping on her kimono. He tries several times to stab the courtesan, but she nimbly rolls out of the reach of his sword each time. At the very last minute, she’s rescued by several guards, who pull Jirō away from her.

The focus shifts to Otsuru as, with the same steely determination with which she had risen to head courtesan, she struggles desperately to survive. She’s seen crawling on the ground, like an animal, to the locked gate. Pulling herself up to a standing position, she futilely struggles to raise the bar on the gate to escape the mad silk merchant. Meanwhile, Jirō, simply through the unpredictability of his movements, has managed to situate himself between the guards and Otsuru. Finally, crying out “You’re mine now,” Jirō stabs the courtesan in the back. When Otsuru falls, leaving her handprints on the gate (a brilliant detail), the lunatic appears horrified by his own act.

Jirō then turns to the guards, or rather to the whole rotten culture of Yoshiwara, and cries out to all the scoundrels there to come out so he can kill them all. In a masterly crane shot, we slowly pull back from Jirō – a good man turned into a monster by the pleasure quarter – as a veritable rain of cherry blossoms falls on the scene. I saw this ending a half-dozen times at least before it occurred to me that this detail is illogical, deliberately so: the tops of the cherry trees are depicted as below the source of the cherry blossoms. It’s as if the blossoms are falling from heaven – a benediction on Jirō’s revenge.

1960 was definitely not the greatest year in the justly-celebrated Golden Age of Japanese Cinema: it was merely extraordinary. There appeared in that year many major movies by great moviemakers. Ichikawa Kon released his prize-winning Meiji-period drama Her Brother (Otōto), a film that to be honest doesn’t do very much for me, despite fine acting and innovative cinematography by the great Miyagawa Kazuo. As already mentioned, Kurosawa made his classic thriller The Bad Sleep Well in that year, and Ozu directed one of his very last films, the elegiac Late Autumn (Akibiyori), which includes a lovely star performance by Hara Setsuko.

Also in 1960, Shindō Kaneto released his worldwide hit The Naked Island (Hadaka no shima), a flawed film – the music, for instance, is repetitive and banal – which nevertheless features stunning cinematography and a remarkable, totally wordless performance by the underrated actress Otowa Nobuko. Kinoshita Keisuke put out a fascinating, epic period movie, perhaps his answer to Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai, called The River Fuefuki (Fuefukigawa), which boasts exceptional work by actress Takamine Hideko. Takamine in the same year also starred in one of Naruse Mikio’s best-known films about modern Japanese women, When a Woman Ascends the Stairs (Onna ga kaidan wo agaru toki). And finally, the young rebels of the Japanese New Wave (nuberu bagu) made a huge splash, with Imamura Shohei releasing the hilarious Pigs and Battleships (Buta to gunkan), and the movement’s “bad boy,” Ōshima Nagisa, releasing no less than three important movies back to back: Cruel Story of Youth (Seishun zankoku monogatari), The Sun’s Burial (Taiyo no hakaba) and the searing political melodrama Night and Fog in Japan (Nihon no yoru to kiri).

Yet Hero of the Red-Light District impresses me more, and moves me more deeply, than any of the above films, even Kurosawa’s. My high opinion of the film has never been echoed by Japanese critics, at that time or later.4 But my experience watching it with a Western audience proves that it packs a visceral punch that only a handful of Japanese productions can match. And if this website succeeds in making just this one work by Uchida better known to movie fans, it will have done its job.

One of Uchida’s darkest films, this masterpiece is the finest work of Uchida’s “classical” style, with great performances by, among others, Kataoka Chiezō and Mizutani Yoshie.

Window on Worlds (Hayley Scanlon)

IFFR (International Film Festival Rotterdam) (2005)

MOMA Uchida Retrospective (2016 series)

Senses of Cinema (Alexander Jacoby) – The film is briefly critiqued within an overview of the director’s career

Weird Wild Realm (Paghat the Ratgirl blog)