Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

(Continued from page 1)

This movie has a status unique in Uchida’s oeuvre (and perhaps in anybody’s oeuvre) in that it’s both a sequel to a film Uchida himself had made more than three decades earlier and a remake of a much more recent movie by another filmmaker. The narrative updates the story of the wise, noble yakuza Kiratsune (or Kira Tsune), whom Uchida had introduced in his acclaimed 1936 film, Theater of Life: Youth Version (Jinsei gekijō – Seishun hen), and depicts the aging character’s complex interaction with two younger yakuza: the sensitive Hishakaku ( or Kaku) and another member of Kaku’s gang, Miyagawa, who unwittingly involves himself in a romantic triangle with Kaku and his beloved common law wife, Otoyo. This odd relationship had been previously explored in another Toei film released five years earlier: Theater of Life: Hishakaku (Jinsei gekijō – Hishakaku, 1963) by the minor director Sawashima Tadashi, which launched the fad for yakuza films that lasted throughout the 1960s, and in which Tsuruta Kōji and Takakura Ken portrayed more or less the same characters as in Uchida’s film.

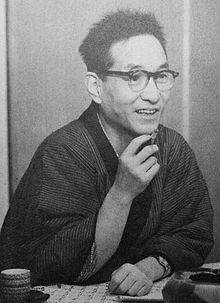

The persistence of these familiar characters and plots attests to the enduring popularity of the novels of Ozaki Shirō on which all these films are based. Ozaki had more than crime and criminals on his mind when he created his books. Like so many early 20th Century Japanese writers, he was obsessed with the seismic shifts that had occurred in his society over the previous half-century, as the culture began to be permeated by Western influences, following the end of its centuries-long isolation. Set in the Meiji and Taisho eras, the Theater of Life (Jinsei gekijō) novels dramatized the vast changes in values, morals and mores that had taken place during those tumultuous, confusing times, which is why they proved fascinating to ambitious filmmakers like the young Uchida.

In 1965, Uchida had become a freelance filmmaker at last after severing his contract with Toei, following the release of the final installment of the Miyamoto Musashi series. Apparently, he received many tentative offers to direct projects from different studios, but none of these plans materialized, forcing him to accept the Theater of Life proposal from Toei (a pet project of producer Shundo Hiroji), despite the fact that he had no desire to work again with that studio, following his bitter experience with A Fugitive from the Past. (Three years had elapsed between the release of the final Musashi film and this one, one of the longest gaps in Uchida’s postwar career.) Although this film and the 1936 one were adapted from different Ozaki novels, the director, according to screenwriter Suzuki Naoyuki in his book on Uchida (as reported in Japanese Wikipedia), felt somewhat depressed about having to revisit the same set of characters, even after a gap of many decades.

Alexander Jacoby, in his summary of the career of Uchida on the Senses of Cinema site, dismisses this film as “mediocre.” I can well understand why Jacoby didn’t think very highly of it, as the movie might seem at first glance to be a routine reworking of standard yakuza genre conventions of the period. And the suspicion that this was an imposed assignment on which the director worked rather reluctantly has at least some basis in fact, as we’ve indicated.

However, a deeper examination of the unusual ways the director handled this well-worn material reveals a work somewhat more complex than a mere genre potboiler. Throughout his career, his commitment to cinema was so strong that, once he began a project, he was psychologically incapable of “phoning it in.” He almost always managed to find something in whatever he was working on to spark his interest – in particular, possibilities for experiments in visual style – and this film is no exception.

A comparison between Sawashima’s 1963 film and Uchida’s movie reveals that, though the earlier work is somewhat better paced and, arguably, the more dramatically effective of the two, Uchida’s pictorial approach is more elegant and more visually powerful and appealing. For example, there’s a brief but very interesting scene in which Kaku and his friend, the gang member Terakane, meet on a bridge. It begins with a shot at the base of this bridge, then the camera cranes upward to find the two men in medium long shot, holding umbrellas and talking in the rainy weather.

The camera then moves in to a closer shot of the two men talking. A road is visible behind the heads of the men, and on this road, a solitary rickshaw, an almost ghostly object at that distance, comes into view. The viewer may at first register this only as an inconsequential detail, but the two men’s attention is suddenly drawn to the vehicle and they begin to discuss it. We then see, at the level of the road, the rickshaw approaching in a medium shot, followed by an interior closeup of the passenger sitting inside the vehicle: it is Otoyo, looking very depressed.

We return briefly to the men on the bridge, and the scene ends again at the level of the road, with the rickshaw passing the camera and then disappearing into the distance. In this way, the dramatic focus of the scene shifts from the men on the bridge to the object of their shared concern – Otoyo – and then back again, in a manner that’s visually compelling.

Many scenes contain shots as scrupulously yet unfussily composed as anything in Ozu’s late films. A good example occurs in the scene at the inn late in the film. The young yakuza Kaku looks out the window while the older one, Kiratsune, is seated on a tatami mat in front of a chabudai (low table). This slightly uncentered shot, photographed by Nakazawa Hanjirō – who had also lensed the masterpiece A Fugitive from the Past for Uchida – shows Kaku on the left with his back to the camera, while Kiratsune is sitting in the center-right of the frame, looking at Kaku. Regular rectangles are formed by the shoji screens in the rear and by the bars on the windows, creating a strong visual rhythm.

Every detail of the shot, including the vases on the floor and the chabudai, is precisely placed. Yet the ultimate effect of this uncluttered shot is to create suspense, since we realize that Kiratsune knows the truth about the destruction of the Kokin gang and Otoyo’s betrayal, and that he is about to inform Kaku. So the entire focus of the shot is on the older man, though he is in the “lower” position.

This film was the last Uchida ever made in his “classical” style, that is, in the same coolly ironic, unhurried, unemphatic visual manner of his previous movies Chikamatsu’s Love in Osaka (1959) and Hero of the Red-Light District (1960).1 If A Tale of Two Yakuza is not as powerful as those masterpieces, that’s partly because its narrative isn’t nearly as interesting, but also partly because of the absence here of the ironic juxtaposition of a detached style with tragic content (in this film, the protagonist survives) so characteristic of those great earlier works.

Describing those films that focus on the earlier period of novelist Ozaki Shirō’s multipart saga (that is, on the Meiji era), including Uchida’s 1936 movie, the online critic/scholar Paghat the Ratgirl explains, “These versions rather than yakuza films are part of the genre called Meiji-mono, about weak men who fail to make it through the changes of the Meiji Restoration with their own masculine authority intact. The ‘weak hero’ of Meiji-mono films are [sic] invariably involved with strong & loving women who are more apt to be able to keep families, or the nation, from falling apart.”

Though Uchida’s 1968 film, set in the Taisho era (roughly, the early 1920s), focuses more on the male world of gangsters than on the domestic realm, Uchida doesn’t ignore the gender issues that Paghat maintains are implicit in Ozaki’s narratives. Like Sawashima’s 1963 version of the story, much of the dramatic focus is not on the clash between the rival gangs, but upon the romantic relationship between Kaku and Otoyo, and on Otoyo’s struggle between the competing claims of ninjō (inclination) and giri (duty), which is every bit as intense and complex as that experienced by Kaku as a yakuza.

In her blog, Paghat (with her typically eccentric punctuation) eloquently describes this conflict: “Kaku snared by his own obligation ends up stabbing one oyabun [gang boss] in service of another, & consequently serves four years in prison. During that time, Otoyo turns to Miyagawa for protection & ultimately affection. [The couple] struggle against their feelings, as they love & respect Kaku. If they act on their feelings, they will be the worst imaginable betrayers & hate themselves always. If they ignore their feelings, they will live unfulfilled lives. Their affair exactly parallels the chivalrous yakuza’s pull between giri (duty) & ninkyo (humanity), or obligation & chivalry.”

In his review of Sawashima’s film, which he regards as the seminal yakuza film of the 1960s (it jump-started the era’s yakuza film craze), the blogger for the Japanonfilm website singles out for praise the actress Sakuma Yoshiko, who portrays Otoyo, for her emotional intensity and directness.2 But for me, Fuji Junko, whom Uchida cast as Otoyo in his film, gives at least as strong a performance as Sakuma’s. Her interplay with Tsuruta in the first scene in which her character appears – in which she embraces him from behind, pulling off his kimono and exposing his shoulder – though less explicitly a “sex scene” than the corresponding sequence in the Sawashima film, is actually more erotic. Among the young Japanese actresses of her day, Ms. Fuji – who had (and has) a distinctively long and beautiful, almost swanlike, neck – seems to have occupied a kind of middle ground between the overt sexuality of Wakao Ayako and the cold, distant elegance of Iwashita Shima. She’s not implausible when she plays a prostitute later in the film, but on some level she never quite ceases to be a lady.

Particularly effective is the scene in which Otoyo discovers, to her horror, that Miyagawa is attached to the Kokin gang, the same group with which her imprisoned husband is affiliated, which makes her relations with Miyagawa a terrible betrayal of Kaku… a kind of treason. Otoyo’s prostitute friend, the well-meaning Osode, discovers that Miyagawa’s friend (who has accompanied him to the brothel) is a Kokin gang member and innocently presents his jacket, with the gang’s kanji characters emblazoned upon it, to Otoyo. The latter then checks out Miyagawa’s jacket (which he has discarded on the floor), which shows the same characters printed upon it, and sinks into grief and sorrow, as if Kaku in prison had just died. In a way he has, because she now, in her shame, can’t bear to face him after his release.

Several critics (including film historian Georges Sadoul, who probably never saw even a single one of Uchida’s films3) have asserted that the director’s postwar films represent an artistic decline from his prewar masterpieces. Elsewhere, I’ve argued that so few of Uchida’s films from the first half of his career survive – and most of those in incomplete form – that any valid overall comparison between his prewar and postwar work is simply impossible. However, there is one aspect of his art about which I can confidently venture a judgment concerning the relative merits of the two eras, and that is Uchida’s ability to direct actresses effectively, which is incomparably superior in his films of the postwar period.

If we were to set, for example, the perfunctory acting of the women in the early near-masterpiece Police Officer (1933) beside the stunning performances of Arima Ineko in Chikamatsu’s Love in Osaka, or Yamada Isuzu in The Horse Boy (1957), or, above all, Hidari Sachiko in A Fugitive from the Past (1965), it would be as if we were looking at the work of two different directors. And perhaps we would be. Maybe something happened to Uchida during his years in China which transformed the way he regarded women, which made him far more sensitive to their inner lives. In any case, the powerful emotions that he manages to draw from Fuji Junko in this film would have been, in my opinion, totally beyond the capabilities of the young Uchida before the war.4

(Continued on page 3)