Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

(Continued from Page 2)

The film has several significant flaws. The most obvious one is the tasteless propaganda that appears near the end, in the scene in which dozens of policemen on motorcycles rush to the robbers’ hideout. Visually, the shot is very impressive, with the cycles racing dramatically through the rainy streets at night… until the intertitles suddenly proclaim the policeman’s official code: “The mission of a police officer is to guard the peace of the nation and the serenity of society, to protect the lives and property of the populace and allow them to live in peace…”

It’s as if, in a modern film, a gripping police chase were suddenly interrupted by a cop with a megaphone screaming “Protect and Serve” slogans. This blatant boosterism, coming so late in the film, is extremely jarring.

However, Uchida would later admit in his memoir that this was the price he had to pay for getting the Minister of the Interior’s cooperation in the creation of the film. As the director put it in his memoir, quoted by Max Tessier here: “Censorship prevented me from describing the internal sufferings and life as a human being of a policeman. As a result, the [original] theme, which was that of the ‘human policeman,’ became that of the ‘courageous policeman.'”1

However, Uchida is not quite correct, because, despite the censorship, the humanity of Officer Itami does indeed come through – including an all-too-human propensity for screwing up. Early in the film, when Tetsuo casually asks Itami how the robbery investigation is going, Itami openly shares with his friend, whom he hasn’t seen in years, the police force’s frustration with the investigation – an extremely unprofessional thing to do. Later in the film, when Itami perceives that Tetsuo no longer trusts him, and thus ought to be seeking to reassure Tetsuo so as to allay his suspicions, he instead perversely provokes those suspicions.

In these and other ways, Itami shows himself to be more brave and stalwart than clever.

An aspect of the film that can be faulted is that it sometimes gives us too much of a good thing, as when Uchida goes overboard in his penchant for visual flourishes derived from German Expressionism. Many of these are, admittedly, effective. To illustrate the tightening of the police dragnet over the city, for example, Uchida displays a chain-link fence superimposed, in double exposure, over aerial images of the city, with the links becoming narrower (by pulling the camera back rapidly from the fence) to show the police closing in on their quarry.

But other effects don’t work nearly as well. When Itami is finally able to confirm his friend’s guilt through a fingerprint matchup, the policeman, who is sitting down, suddenly and melodramatically throws his head back in grief and despair. But the stylized image, which Uchida shoots from multiple angles, is over-emphasized, and so we merely perceive, but do not really feel, the character’s pain.

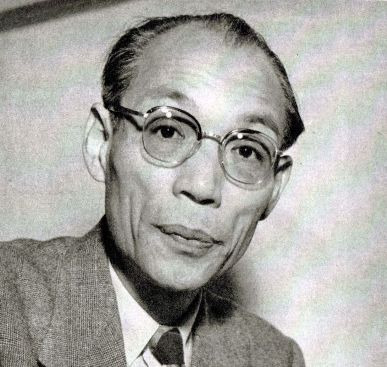

But this is a minor fault in a classic urban crime thriller, a work that proved that Uchida, only about 35 years old at the time, was already not just one of Japan’s, but one of the world’s major moviemakers.

Police Officer was made during the brief period in the early-to-mid 1930s when Uchida was trying to throw off the shackles of Nikkatsu, the studio he had been working for since 1926. Throughout his career, Uchida chafed, more perhaps even than most filmmakers, under the restrictions that various studios imposed upon him, and apparently his relationship with Japan’s oldest and most conservative studio had reached the breaking point. And he was definitely not alone in his dissatisfaction. He joined a group of disgruntled Nikkatsu filmmakers that called itself the Team of Seven (nananin-gumi), which included Mizoguchi Kenji, Itō Daisuke, Murata Minoru (director of the pioneering Souls on the Road (Rojō no reikion, 1921)) and Tasaka Tomotaka (later the director of the classic war film Five Scouts (Gonin no sekkōhei, 1938)).

Together the seven founded a new company, Shin-Eiga-Sha (“New Motion Picture Company”), which rented studio space from another new company, Photo Chemical Laboratories (P.C.L., which would soon morph into Toho Studios).2 The new filmmakers’ studio was not a success. Uchida would make only one film for it: Asia Cries Out (Sakebu Ajia, 1933), with a script by Itō Daisuke, which was, according to Peter High, a pro-militarist film.3

When Shin-Eiga-Sha went belly up, Uchida considered going to work for the minor studio Shinkō (full name: Shinkō Kinema). That company had its own troubles, however. According to Richie and Anderson, the director Kimura Sotoji had earlier organized a strike there, and management had sent gangsters to break it up; Kimura responded by leaving the company permanently along with many other strikers, eventually ending up at Toho.4 (Kimura would play a major role in the events involving Uchida’s time in China: see the China Adventure section of my Uchida biography on this website.) This left the small studio in desperate need of experienced talent. So despite these ominous signs, Uchida signed with Shinkō, and his first production there was this film, which was heavily sponsored, as mentioned earlier, by the Ministry of the Interior. Although he was clearly given the freedom to achieve the visual style he desired, the censorship, as noted, distorted the film’s central theme of the inner torment of the policeman-hero.

Uchida made three more films for Shinkō – Sun over the River (Kawa no ue no taiyo, 1934), Hot Wind (Neppu, 1934) and the two-part The Silver Throne (a.k.a., The White Man’s Throne) (Hakugin no oza, 1935) – before conceding defeat and returning to Nikkatsu in 1936.5 However, at Nikkatsu in the mid-to-late 1930s, he would achieve perhaps his greatest professional prestige, with one important work after another: Theater of Life (Jinsei gekijo, 1936), the lost The Naked Town (Hadaka no machi, 1937), and the one-two punch of Unending Advance (Kagirinaki zenshin, 1937) and Earth (Tsuchi, 1939), both chosen as “film of the year” by critics. However, after making the (lost) three-part film History (Rekichi, 1940), Uchida quit Nikkatsu again to set up yet another production company, which predictably failed.

It should be noted that the only prewar Nikkatsu film by Uchida that survives in its entirety is the minor silent comedy Sweat (Kigeki: Ase, 1929). So it was fortunate for us that he made a career detour to work at Shinkō, since because of that, we now have the much more important silent film, Police Officer.

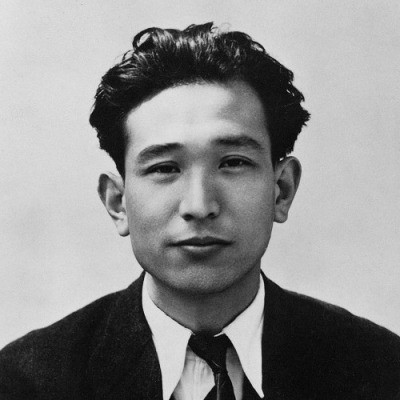

A viewer possessing even a casual familiarity with the work of Kurosawa Akira would probably have already noted a very strong resemblance between this film and the younger director’s classic 1949 movie Stray Dog (Nora Inu), widely acknowledged as one of the first great detective films in Japanese Cinema. The narrative of Kurosawa’s film concerns a young policeman, Murakami (Mifune Toshirō), who carelessly allows his pistol to be stolen on a crowded bus by a boyish thief, who turns out to be very similar in background and history to himself.

Murakami soon meets and bonds with an older detective, Satō (Shimura Takashi), who’s been assigned to the case of the stolen pistol. Partly through forensics, the two detectives close in on the thief, who by now has murdered somebody… with that same pistol. Just when an arrest seems imminent, the crook eludes the dragnet, but not before seriously wounding Detective Satō with Murakami’s own gun. The young policeman, who nearly goes mad with guilt, sets out on an obsessive, deeply personal quest to recover his weapon and apprehend the man at all costs. After a long, dramatic chase, Murakami finally succeeds in capturing and arresting the criminal.

The thematic and dramatic parallels between Police Officer and Stray Dog should be instantly obvious: the uncomfortably close affinity between cop and criminal; the warm, quasi-paternal relationship between the older cop and the younger one; the forensic investigation to determine the identity of the perpetrator; the shooting of the older policeman during the criminal’s desperate escape; the hero’s solitary quest to solve the crime; the final, prolonged chase.

Kurosawa, as far as I know, never publicly admitted to being influenced by this Uchida movie… or any other. Discussing Stray Dog in his autobiography, Kurosawa wrote that he wanted to film a story that would evoke the fiction of one of his most admired contemporary writers, the Belgian novelist Georges Simenon, creator of the famous fictional detective, Jules Maigret. In fact, the filmmaker at first composed the narrative as an unpublished Simenon-like novel, before adapting his own fictional work into script form.6

But even if the novels of Simenon were the primary inspiration for Stray Dog, Uchida’s film was almost surely a strong secondary one. In 1933, when Police Officer came out, Kurosawa, whose original career goal was to become a successful painter, had not yet joined the film industry, or was even thinking of joining it. But his autobiography makes clear that he had been, for many years, an ardent movie fan, partly under the tutelage of his older brother and mentor Heigo, who worked as a benshi (silent movie narrator) before his tragic suicide. And though the young Kurosawa’s primary aesthetic interest lay in foreign films (including Hollywood ones), he also reveals that he saw and admired some Japanese ones as well, like the work of Uchida’s friend and future collaborator, Itō Daisuke.7

Furthermore, Uchida had established a reputation as a promising young director by the late 1920s with A Living Puppet. Both he and his work were highly publicized. So though it’s certainly possible, it’s not at all likely that the impressionable 23-year-old cinephile Kurosawa would have missed Police Officer during its initial run.

In his autobiography, Kurosawa never so much as mentions Uchida. But, in the 1990s, near the very end of his life, the great filmmaker created a list of his 100 favorite films (which is actually a list of films by his 100 favorite directors, since he limits himself to only one film per director). In that list, he cites Uchida’s Earth as one of these favorites, and implies in his commentary that he might easily have chosen instead his previous film, Unending Advance.

An examination of the influence of the work of Uchida on that of the younger film master – and I think they had much in common – would serve, I believe, as an intriguing subject for future film scholarship.

A first-rate and visually stunning action melodrama, ultimately lacking only the depth the filmmaker would achieve in his later work. A silent masterpiece!

San Francisco Silent Film Festival: 2018 (Eddie Muller of cable channel TCM)

Japanonfilm (blog)

Museum of Modern Art (2016 retrospective)

CEAS (Yale University 2015 screening)

Senses of Cinema [brief mention of the film] (Alexander Jacoby)

Tokyo FILMeX (2004 retrospective)

Pod Hard (2020 podcast)

Throw Out Your Books (background on the 1932 Ōmori bank robbery)

[…] Police Officer (Keisatsukan, 警察官), 1933 […]

[…] Sakaba; たそがれ酒場), 1955A Bloody Spear at Mount Fuji (Chiyari Fuji; 血槍富士), 1955Police Officer (Keisatsukan, 警察官), 1933The Mad Fox (Koiya koi nasuna koi; 恋や恋なすな恋), […]

[…] Fuji (Chiyari Fuji; 血槍富士), 1955Twilight Saloon (Tasogare Sakaba; たそがれ酒場), 1955Police Officer (Keisatsukan, 警察官), 1933The Mad Fox (Koiya koi nasuna koi; 恋や恋なすな恋), […]

[…] Bloody Spear at Mount Fuji (Chiyari Fuji; 血槍富士), 1955Police Officer (Keisatsukan, 警察官), 1933Twilight Saloon (Tasogare Sakaba; たそがれ酒場), 1955The Mad Fox (Koiya koi nasuna koi; […]

[…] the exception of Police Officer (Keisatsukan, 1933), Sweat, a comedy he released in 1929, is the only complete, surviving silent […]

[…] on the above description, this movie would seem to take the ideology of Police Officer into a 19th Century narrative, with a stronger pro-government emphasis. Despite its apparent […]

[…] Police Officer (Keisatsukan, 警察官), 1933A Bloody Spear at Mount Fuji (Chiyari Fuji; 血槍富士), 1955Twilight Saloon (Tasogare Sakaba; たそがれ酒場), 1955Chikamatsu’s Love in Osaka (Naniwa no koi no monogatari; 浪花の恋の物語), 1959 […]