Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Alternate Titles: Horse Boy1; Hooligans’ Highway (literal English title); La Route des malandrins (literal French title)

| Production Company | Toei (Kyoto) |

| Scenarist | Yoda Yoshikata |

| Original Draft (uncredited) | Hirata Kenzo (see Notes on the Production below) |

| Sources | The Night Song of Yosaku from Tanba (Tanba Yosaku machiyo no komurobushi (Bunraku [puppet] play, ca. 1708) by Chikamatsu Monzaemon,2 and Shigenoi’s Farewell to Her Child (Shigenoi Kowakare), Act 10 of the 13-act Kabuki play based on Chikamatsu’s work, The Loving Wife’s Parti-colored Reins (Koi Nyōbō Somewake Tazuna, 1751) by Miyoshi Shōraku and Yoshida Kanshi I. |

| Cinematographer | Yoshida Sadaji |

| Production Designer | Tamaki Jun’ichirō |

| Art Direction | Suzuki Takatoshi |

| Music | Fukai Shirō |

| Performers | Sano Shūji (Yosaku, a former samurai, now a ronin), Yamada Isuzu (Shigenoi, formerly Shigeno, daughter of Kotayu and guardian of the princess), Ueki Motoharu (Sankichi, a boy pack-horse driver); Chihara Shinobu (Koman, a former prostitute); Shindō Eitarō (stable master, employer of Sankichi); Susukida Kenji (Kotayu, chief retainer of the Yurugi clan); Oka Satomi (lady in waiting); Mōri Kikue (serving woman); Fujita Mami (princess) |

| Status | Extant |

| Photography | Black-and-white |

| Format | 35mm |

| Ratio | 1:37:1 |

| English Subtitles | Yes / No3 |

| Original Release Date | February 19, 1957 |

| Length | 95 minutes |

| Festival/Retrospective Screenings | Tokyo FILMex (2004); BFI Southbank (2007); Museum of Modern Art retrospective (2016) |

During the feudal era, the powerful Yurugi clan resides in a castle at Tanba province (corresponding in part to today’s Kyōto and Hyōgo prefectures). Yosaku, a samurai dressed as a peasant, tries to gain access to the castle through the main gate, but is denied. However, a sympathetic retainer lets Yosaku in through a small door in the gate. Yosaku, carrying an infant’s toy, attempts in vain to enter the mansion of the Inaba family, whose patriarch, Kotayu, is the clan’s chief retainer.

Meanwhile, a young woman, Shigeno, Kotayu’s daughter, has just given birth to an illegitimate child, Yonosuke, Yosaku’s son. Her father chastises her for this transgression, though she clearly loves both Yosaku and the baby. Against her wishes, he decides that the boy will be given up for adoption and that Shigeno will henceforth be known as “Shigenoi” and be assigned as a wet nurse to the clan’s newborn princess. Shigenoi is carried out of the grounds in a palanquin to begin her “exile,” while the baby is removed from the castle to be given over to the care of a poor family.

Eleven years later, Yosaku, now a wandering ronin, is walking down a highway with no apparent fixed destination or goal. He stumbles upon a scene in which a wealthy woman asks a young boy, a pack-horse driver named Sankichi, who is smoking a pipe, to give her son a ride on his horse. The child rudely rebuffs her without giving a reason, but cheerfully offers a ride to the ragged and tired Yosaku.

The boy and Yosaku, who is riding Sankichi’s horse, enter the town of Seki. From an upstairs window of an inn, Koman, a former prostitute, who has been taking care of Sankichi, watches Yosaku’s approach with amusement. The ronin, calling himself “Genjirō,” rents a room at the inn, where he and Koman become increasingly attracted to one another. However, the feckless man soon gambles away what little money he has, and is forced to move out of the inn and into the tiny hut in which Sankichi lives.

The boy promises to give the ronin work as a horse driver, and their friendship deepens. With his wages, the child buys a bottle of sake for Yosaku, but when he sees him chatting in a friendly way with Koman, the boy becomes jealous and upset and has a violent tantrum, during which he smashes the bottle of sake. Yosaku understands and forgives him, and promises to act as a surrogate father to him from now on.

A long, elaborate procession, in which the young princess of the Yurugi clan is being carried in a palanquin, approaches the town of Seki. The princess suddenly pulls a tantrum and gets out of the palanquin, bringing the procession to a halt. Shigenoi, her nurse, tries to persuade the girl that Edo (now known as Tokyo), the capital, is much more fun than Tanba and that she should be honored to become the bride of a wealthy lord there, but the child just wants to go back to Tanba and her mother. The girl encounters Sankichi in the road playing the board game sugoroku4 with other horsemen, and is clearly enchanted by both the game and the young horse driver. To calm the princess down, it’s decided to bring the boy with them to the inn at Seki, so he can play the game with her there.

While at the inn, the boy is presented to Shigenoi, who’s amused by him until she notices that an amulet he is carrying has exactly the same design as the one she had sewn for the infant Yonosuke before he was taken from her. After questioning him, she realizes that the horse boy is her long-lost son. However, when he points out that her name is similar to the name (Shigeno) he had been told is his mother’s, she denies the connection. Shortly afterwards, one of the serving maids calls her by her old name, Shigeno, in the boy’s presence, and Sankichi, realizing she was lying, becomes furious and storms off. She offers him money, but he indignantly refuses it and departs, much to her distress.

One night in Sankichi’s hut, believing the boy to be asleep, Yosaku and Koman discuss the latter’s financial dilemma. Her father is deeply in debt with overdue taxes, she tells the ronin, and she may have to resort to prostitution again to get the money the old man needs. Having secretly overheard this conversation, Sankichi returns to Shigenoi and rudely demands the money that he had rejected before. Puzzled, she asks why he wants it, but he refuses to give a reason, and she declines to offer it again. He leaves and angrily throws the amulet, the proof of his samurai origins, into the river.

In the middle of the night, Sankichi sneaks into the room where the princess is sleeping. In a box, he finds a katana (sword), intended as a wedding present for the girl’s future husband, and leaves with it. The boy then goes to a tavern and, finding there the stable master, his employer, he offers to sell the katana to him for five ryō. When the man asks him where he got the weapon, the child refuses to say, though he swears that he’ll never reveal he sold it to him. Sankichi then appears below Koman’s window and throws a handkerchief up to her. She opens it and finds five ryō there.

Meanwhile, the chief retainer has discovered the theft of the katana and suspicion falls on Sankichi. Yosaku has just realized that Sankichi is his son when the boy is arrested by the clan’s guards. He appears before Shigenoi and Kotayu and admits to taking the weapon, but won’t say why he took it or where it is. He berates his mother for his hard life as a horse driver, which he blames on her abandonment of him.

Yosaku runs off in search of the stable master. Meanwhile, the latter has been informed that the weapon was stolen from the Yurigi clan, and he sets off to return it to them for a 10-ryō reward, though this would mean Sankichi would be executed. Yosaku catches up with him and, seeing the katana in his hand, to save his son’s life offers to buy it from him for five ryō, which is all he has. The man scoffs at this offer and literally brushes him aside.

After attempting various strategies to get him to give up the katana, Yosaku finally tries to pry it out of his hands. The stable master draws a knife and lunges at him. The two men fall to the ground and scuffle until they fall into a ditch, where the stable master is accidentally stabbed by his own weapon and dies.

At the inn, Kotayu threatens to turn Sankichi over to the magistrate. A retainer, however, informs the old man that Yosaku, or rather his corpse, is in the courtyard, as he has just committed seppuku. On his person, they discover the katana and a document in which Yosaku before he died explained the situation and took full responsibility for what had happened with the weapon, exonerating the boy. Both Koman and Sankichi enter and weep over the ronin’s dead body. The boy cries even harder when Koman informs him that Yosaku was his father. Shigenoi collapses, wondering how such terrible things could happen in the world.

At dawn the following morning, Shigenoi bids a final farewell to her son and leaves him in the care of Koman. The princess, no longer rebellious, willingly enters her palanquin, and the long procession (presumably including Shigenoi) leaves to continue on its journey to Edo.

The blogger would like to thank Hayley Scanlon for her kind assistance in creating this synopsis.

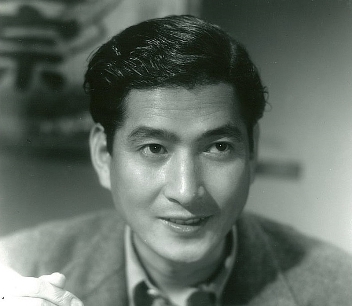

Yamada Isuzu was one of Japan’s most distinguished actresses, and she also enjoyed one of that nation’s longest careers as a star: from the early 1930s to the turn of the 21st Century. The daughter of an actor, Yamada as a child was extensively schooled in traditional music and dance, and Japanese Cinema scholar Donald Richie has claimed that this early training strongly influenced her art throughout her life. She began her film acting career as a young teenager with Nikkatsu studios, so although she was only fourteen when she starred in Uchida’s lost silent film, The Revenge Champion (Adauchi senshu, 1931), this was already her ninth film in two years. During the 1930s, she worked often with Mizoguchi Kenji, and in 1936, that director gave the still-teenaged actress two of her most memorable roles as defiant modern women in Osaka Elegy (Naniwa erejī) and Sisters of the Gion (Gion no shimai). She was one of the few actors who managed to collaborate with all the “big four” Japanese directors: in addition to Mizoguchi, she performed many times for Naruse Mikio, including in The Song Lantern (Uta andon, 1944) and Flowing (Nagareru, 1956); once for Ozu Yasujirō, in Tokyo Twilight (Tokyo boshuku, 1957); and three times for Kurosawa Akira, all as memorable villains, particularly the sinister Lady Washizu (i.e., the “Lady Macbeth” character) in his famous Shakespeare adaptation, Throne of Blood (Kumonosu-jō, 1957). In her films widely seen in the West, she most often portrayed evil or transgressive characters, but she could play sweet and compassionate women equally well, as she proved in The Horse Boy and Chiba Yasuki’s poignant drama of ordinary people, Downtown (Shitamachi, 1957), both released in the same year as Throne of Blood. Her private life appears to have been tumultuous: it’s been variously reported that she was married four, five or even six times. (Yamada’s daughter, actress Saga Michiko, would later portray the leading female character(s) in Uchida’s The Mad Fox (1962).) Beginning in the 1960s, as the film industry declined, Yamada, like many of her peers, appeared more often in television than in films, and also maintained a busy stage career. Her final credit on IMDb is for a TV series broadcast in 2000, when she was in her eighties. She died in 2012, age 95.

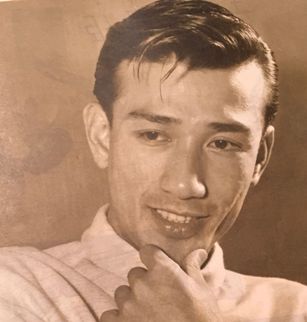

Sano Shūji was an actor notable mostly for his performances in the 1940s and 1950s. In his early twenties, during the prewar period, he was signed by Shochiku, where he soon was recognized as one of the studio’s most promising young actors. In 1937, he was cast with two other rising male stars, Uehara Ken and Saburi Shin, in Shimazu Yasujirō’s satirical comedy, The Trio’s Engagement (Konyaku sanbagarasu), and though Saburi and (particularly) Uehara went on to become major stars, Sano never quite reached that level of celebrity. Nonetheless, he made outstanding contributions to the films of several major directors, particularly those of Ozu Yasujirō – as the grieving son in the moving There Was a Father (Chichi Ariki, 1942) and as Hara Setsuko’s unpleasant boss in Early Summer (Bankushu, 1951) – and Kinoshita Keisuke, especially his classic comedy Carmen Comes Home (Karumen kokyō ni kaeru, 1951), in which he played a blind war veteran. But perhaps his best performance, at least in gendai-geki (modern) films, was as a troubled business executive who provides help and sympathy to the beleaguered women he meets in Gosho Heinosuke’s classic An Inn at Osaka (Osaka no yado, 1954). He died in 1978 at age 66.

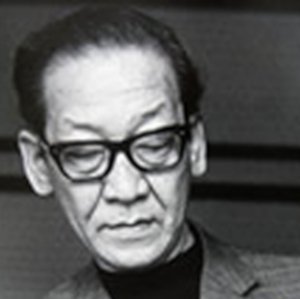

Yoda Yoshikata was one of Japan’s greatest screenwriters. He is best known today for his long, and often adversarial, creative partnership with director Mizoguchi Kenji. (Yoda once said, “In my dreams, I strangled Mizoguchi many times.”)5 Together they worked on 24 films in all, from Osaka Elegy (Naniwa erejī, 1936) to the master’s penultimate work, Tales of the Taira Clan (Shin Heike monogatari, 1955), including such classics as The Life of Oharu (Saikaku ichidai onna, 1952), Ugetsu (Ugetsu monogatari, 1953), Sansho the Bailiff (Sanshō Dayū, 1954) and A Story from Chikamatsu (Chikamatsu monogatari, also known as The Crucified Lovers, 1954). The collaboration could even be said to have survived the director’s death: Yoda wrote the script for Yoshimura Kōzaburō’s An Osaka Story (Ōsaka monogatari, 1957), which was actually Mizoguchi’s final project, derived from an original story he wrote but did not live to direct himself. In addition to the three films Yoda wrote for Uchida – The Horse Boy, Hero of the Red-Light District (Yōtō monogatari: hana no Yoshiwara hyakunin-giri, 1960) and The Mad Fox (Koiya koi nasuna koi, 1962) – Yoda composed scripts for many other distinguished directors, including four films for Misumi Kenji (e.g., Family Tree: Onnakeizu, 1962), and acclaimed works by Itō Daisuke (Five Men from Edo: Oedo gonin otoko, 1951), Shimizu Hiroshi (Sound in the Mist: Kiri no oto, 1956), Ieki Miyoji (Stepbrothers: Ibo kyōdai, 1957) and Yamamoto Satsuo (Ballad of the Cart: Niguruma no uta, 1959). Cruel Tales of Bushido (Bushidō zankoku monogatari, 1963), which he scripted with Suzuki Naoyuki (another Uchida screenwriter), and which was directed by Imai Tadashi, won the top prize, the Golden Bear, at the 1963 Berlin Film Festival. In the 1970s, Yoda wrote several installments of the popular “Bad Reputation” (Akumyō) series of yakuza films. During his final years, he served as professor, then as Dean, of the Department of Film and New Media at Osaka University of the Arts. He was also a published poet. There appears to be no truth to the popular legend that his surname inspired the name of the popular fantasy character Yoda of the Star Wars franchise, first introduced in The Empire Strikes Back (Irvin Kershner, 1980). He died in 1991, age 82.

The Horse Boy was the first of four adaptations of traditional Japanese dramas – called the “classic performing arts tetralogy” (koten geinō shibu-saku) – that Uchida made over a five-year period (1957-1962).6 After this movie, Uchida would film one other Chikamatsu adaptation, Chikamatsu’s Love in Osaka (Naniwa no koi no monogatari, 1959), in which he would ingeniously include the famous playwright as a character in the story (played by Kataoka Chiezō). For both Hero of the Red-Light District (1960) and The Mad Fox, he would adapt works by other traditional playwrights.

The roots of this series lay, intriguingly, in an incident that occurred during Uchida’s long self-exile in China. During most of this period, in which he taught Soviet film editing techniques to young Communist Chinese and Korean filmmakers, he enjoyed precious little contact with Japan and Japanese culture, aside from letters sent to him from his wife back in Tokyo. But one form of contact with old Japan sparked a Proustian epiphany, as he himself describes it:

When I listened to shortwave broadcasts from Japan, I would occasionally hear the sounds of shamisen and taiko drums. At such times, I was overcome with an overwhelming emotion and truly missed Japan. There is a saying that something touches the heartstrings, and I was reminded that I am truly Japanese. I had always wanted to try my hand at the world of Kabuki.7

It should be noted that, in all likelihood, Uchida listened to these broadcasts near the end of his sojourn in China, while he was in the hospital recovering from both the strain of overwork and from accumulated health problems caused by his time working in a coal mine in Manchuria, which had very nearly killed him. His sudden, intense pang of nostalgia for his native culture may thus have been exacerbated by a quite realistic fear that he might never return alive to Japan.

So it was only a few years after his repatriation in 1953 that he began to explore the cinematic possibilities offered by venerable Japanese dramatic literature. His goals for this project were, however, both traditional and anti-traditional. He sincerely wished to honor the spirit of native theatrical forms like Bunraku (the puppet theater), Kabuki and Noh, which he deeply admired. But while in China he had also experienced an epiphany of a different sort. It was there that he read for the first time the works of the Japanese Marxist historian Hattori Yukimasa, whose writings painted a dark picture of his country’s imperialist ambitions, which Uchida had all too recently, and quite fervently, supported.8 Therefore, he now sought to critique the feudal ideology that underpinned these ancient works of art, particularly since, like so many of his filmmaking peers, he understood all too well that destructive feudal attitudes still persisted in postwar, industrialized Japan.

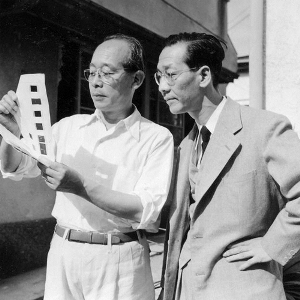

This film marked the first of three collaborations with Uchida by the great screenwriter Yoda Yoshikata, who is most famous for the scripts he wrote for Mizoguchi Kenji (see Notes on the Cast and Crew above). Uchida, over the course of his career, worked with a number of outstanding scenarists, including Kobayashi Masashi (Sweat: Kigeki: Ase, 1929), Yagi Yasutarō (Earth: Tsuchi, 1939), Narusawa Masashige (Chikamatsu’s Love in Osaka, 1959) and Suzuki Naoyuki (A Fugitive from the Past: Kiga Kaikyō, 1965). But Yoda was, in my opinion, the greatest scriptwriter with whom the director ever worked, a master of plot structure, characterization and dialogue. In my review of Hero of the Red-Light District (1960), I argue that the script for that work was the best Uchida ever filmed, at least among his surviving movies.

In light of this, the history of the composition of the script for The Horse Boy is very interesting. According to Fujita Nahiko, three versions of the script still exist, preserved at Waseda University Theater Museum: a mimeographed draft, a handwritten draft and the final version. According to Fujita, internal evidence suggests that the mimeographed document was created first and the handwritten text second.9 However, the writing credits that appear in the three versions are totally different.

In the first surviving document (that is, the mimeographed one), the script is credited to Hirata Kenzo, a writer of contemporary kabuki plays who was closely associated with Shinsei Eigasha – the left-wing, independent film company founded by, among others, directors Imai Tadashi and Yamamoto Satsuo – while Yoda Yoshikata is only given a “composed by” credit. This may signify that, at this point in the project, Yoda was merely working to create the dramatic structure of the film, not to contribute to the dialogue and characterizations. This theory makes sense, since in this first draft, as Fujita stresses, the basic plot and incidents of the drama are more or less those of the final film, though the details are very different, particularly in the cuts that were eventually made, showing a clear progression from the mimeographed to the handwritten version.10

In the second, handwritten manuscript, Yoda clearly has begun to take a much more assertive role, as this version is credited equally to Yoda and Hirata, and the scenario is much closer to the shape of the finished film than the first draft. For the final version of the script, according to Fujita, the screenplay is credited to Yoda alone, with Hirata credited only with the “original draft.”11 12 Apparently, by this time Yoda had completely taken over the screenwriting process – which apparently suited Uchida just fine, since, after the film came out, he publicly praised Yoda’s “detailed and down-to-earth nature” for coming up with what he regarded as a very effective script.13

Yamada Isuzu was apparently the first of the actors cast. Based on a cast list included in the mimeographed script, which includes only the name “Yamada” next to her character’s name, Shigenoi, it can be assumed that she was involved in the project from its earliest stages.14 As already mentioned, she had worked with Uchida on The Revenge Champion (1931) when she was only 14, and had also appeared in Mizoguchi’s Osaka Elegy (1936), the very first film whose script Yoda had written for that filmmaker. She had also already worked on a film produced by Matsumoto Torizō, the producer of The Horse Boy, for the left-wing director Yamamoto Satsuo. Lastly, she had attempted unsuccessfully, with her daughter Saga Michiko, to develop a film based on a Chikamatsu play, Drums of the Waves of Horikawa (Horikawa nami no tsuzumi).15 (A different adaptation of the same play, directed by Imai Tadashi, was released in 1958 under the title Night Drum (Yoru no tsuzumi).) So she was apparently drawn to the project both because she was comfortable with the team of creators, many of whom she’d worked with before, and because she was still eager to work on a Chikamatsu adaptation.16

The role of the samurai-turned-ronin-turned-horse-driver Yosaku was probably intended to be played by the very popular star Sada Keiji, since his surname appears in the cast list of the mimeographed script. But he apparently bowed out of the project for unknown reasons, and his place was taken by his friend Sano Shūji, who had never appeared in a period film before.17

For the role of the title character, Uchida chose Ueki Motoharu, the young son of one of the director’s best friends, actor Kataoka Chiezō, the star of A Bloody Spear on Mt. Fuji (Chiyari Fuji, 1955), Uchida’s comeback film. He had been very impressed by Ueki’s work in Bloody Spear, and so the following year he had cast the boy in both The Kuroda Affair (Kuroda sodo, 1956) and his William Tell adaptation, Rebellion from Below (Gyakushu gokumon toride, 1956). (Following this film, he would cast him once more in a small role in The Eleventh Hour (Dotanba, 1957).) It has been speculated that The Horse Boy was actually intended as a vehicle for Ueki.18

In the final script, Uchida indicated his vision for the film in the Production Intentions section:

A mother in a gorgeous kimono, wiping away tears as she thinks of her son, and a child wandering around pulling the reins of a horse in search of his mother – I wanted to depict the boundless affection between mother and son, and sharply expose the conventions of feudal society that trample even on affection.19

Uchida thus combined his critique of feudalism with the ideology of the “mother film,” which had become a popular genre in Japan beginning in the late 1940s. Although in the prewar cinema, the valorization of mothers who sacrifice everything for their children was by no means uncommon – two notable instances are Shimizu Hiroshi’s The Woman Who Wept in Spring (Nakinureta haru no onna yo, 1933) and his Forget Love for Now (Koi mo wasurete, 1937) – this subgenre of the domestic melodrama was especially popular in the postwar era, in which the suffering mother was turned into a kind of symbol of the Japanese people, abused and betrayed by its wartime government: the Japanese as pure victims, rather than wartime aggressors. The mother film was thus crucial in what Fanglin Wang, in his master’s thesis, calls “the formation of victim consciousness” in postwar Japan.20

Since the historical roots of the wartime Fascist government lay in the ideology of the Japanese samurai class during the feudal period, particularly the centuries-long Tokugawa shogunate, the character of the suffering mother could thus be logically situated within the context of the period film to depict the inhumanity of that ideology. This is probably why the project was greenlighted by Uchida’s studio, Toei, despite the total absence of sword fighting in the narrative. As Uchida’s biographer, Suzuki Naosuke, wrote: “The reason why such a project could survive in Toei, where sword fighting films were at their peak, was probably because the subject matter was wrapped up in elements of tear-jerking mother-tales.”21

Fujita claims that the film was “a commercial success,” but provides no data to support this assertion.22 Surprisingly, the film does not appear as one of the thirty films honored in the Kinema Junpo list of the “best of” films of 1957. This omission occurred despite the fact that Sano Shūji’s performance was acclaimed by critics.23 The Horse Boy was entered by Toei in the main competition at the 7th Berlin Film Festival in 1957.24 The winner of the Golden Bear that year was a Hollywood production – 12 Angry Men, the debut film of Sidney Lumet. The Berlin jury thus appeared to favor contemporary problem films, so the fact that The Horse Boy was a period film – a genre which was largely regarded at that time in the West as escapist – may have worked against it. Five years later, Toei would enter the last of Uchida’s theatrical adaptations, The Mad Fox, another period film, in the Venice Film Festival, with similar lack of success.

(Continued on page 2)