Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Part I: Miyamoto Musashi; Alternate title: Zen and Sword (also used as series title); 宮本武蔵.

Part II: Miyamoto Musashi II: Duel at Hannya Hill; Alternate Title: Miyamoto Musashi: Showdown at Hannyazaka Heights; Original Title: Miyamoto Musashi: Hannyazaka no kettō: 宮本武蔵 般若坂の決斗.

Part III: Miyamoto Musashi III: Birth of the Nito-ryu Style; Alternate titles: Two-Sword Fencing Is Born, Miyamoto Musashi: Birth of the Two Sword Style; Original title: Miyamoto Musashi: Nitōryū kaigan (literally: Two-Sword Fencing Enlightenment): 宮本武蔵 二刀流開眼.

Part IV: Miyamoto Musashi IV: Duel at Ichijyo-ji Temple; Alternate title: Miyamoto Musashi: The Duel at Ichijoji; Original title: Miyamoto Musashi: Ichijōji no kettō: 宮本武蔵 一乗寺の決斗.

Part V: Miyamoto Musashi V: Duel at Ganryu Island; Alternate titles: Duel at Ganrule Isle, Miyamoto Musashi: Musashi vs Kojiro; Original Title: Miyamoto Musashi: Ganryū-jima no kettō: 宮本武蔵 巌流島の決斗.

| Production Company | Toei |

| Scenarists | Narusawa Masahige and Suzuki Naoyuki (Part I); Suzuki Naoyuki and Uchida Tomu (Parts II-V) |

| Source | Miyamoto Musashi (aka, Musashi) by Yoshikawa Eiji (novel: serialized 1935-1939) |

| Producer | Ōkawa Hiroshi |

| Planner | Okada Shigeru |

| Cinematographers | Tsudoi Makoto (Parts I and II); Yoshida Sadaji (Parts III-V) |

| Production Manager | Nemoto Ryōsaku (Part I) |

| Production Designers | Ogawa Takaya and Tsujino Kimiharu (Part I); Ogawa Takaya, Onaga Takao and Tsujino Kimiharu (Parts II-IV)1 |

| Art Director | Suzuki Takatoshi |

| Set Designers | Kamiwa Mineo (Part I); Kan Kiyoshi (Parts II-IV)2 |

| Stunts | Adachi Reijirō (fight choreographer) (Parts III and IV) |

| Music | Ifukube Akira (Part I); Kosugi Taiichirō (Parts II-V) |

| Editing | Miyamoto Shintarō (Parts I-IV)3 |

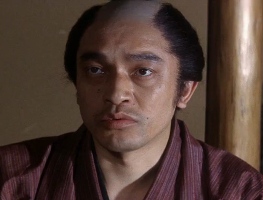

| Performers appearing in all five parts | Nakamura Kinnosuke (Shinmen Takezō, later Miyamoto Musashi), Irie Wakaba (Otsu, fiancée of Matahachi), Kimura Isao (Hon’iden Matahachi, Musashi’s friend), Oka Satomi (Akemi, Okō’s adopted daughter), Naniwa Chieko (Osugi, known as Obaba, Matahachi’s mother) |

| Performers appearing in more than one part | Takakura Ken (Sasaki Kojirō, Parts III-V), Mikuni Rentarō (Takuan, a priest, Parts I, II and V), Kogure Michio (Okō, a bandit woman, Parts I-III), Ebara Shinjirō (Yoshioka Seijurō, leader of the Yoshioka School, Parts II-IV), Takeuchi Mitsuru (Jotarō, Musashi’s servant, Parts II-IV), Kawarasaki Chōichirō (Hayashi, Yoshioka School, Parts II-V), Abe Kusuo (Gon, known as “Uncle,” Parts I-III), Hira Mikijirō (Yoshioka Denshichirō, younger brother of Seijurō, Parts III and IV), Tani Kei (Akakabe, samurai friend of Matahachi, Parts III and IV), Minami Hiroshi (Toji, lover of Okō, Parts II and III), Kuni Kazutarō (Yokōyama, Yoshioka School, Parts II-IV), Hanazawa Tokubei (Aoki Tanzaemon, father of Jotarō, Parts I and IV), Senda Koreya (Hon’ami Koetsu, Parts IV and V), Miyaguchi Seiji (Kisuke, bamboo shop owner, Parts I and II) |

| Performers appearing in one part only | Kazami Akiko (Ogin, Musashi’s sister, Part I), Kaga Kunio (Tenma, bandit chief, Part I), Tsukigata Ryūnosuke (Nikkan, priest at Hozo-in Temple, Part II), Kurokawa Yatarō (Inshun, head of Hozo-in Temple, Part II), Susukida Kenji (Yagyu Sekishusai, Part III), Yamagata Isao (Elder Mibu, uncle of Seijurō, Part IV) Tōno Eijirō (Haiya, a merchant in Kyoto, Part IV), Satō Kei (Otaguro of Yoshioka School, Part IV), Iwasaki Kaneko (Yoshino tayū, a geisha, Part IV), Higashiyama Chieko (Koetsu’s mother, Part IV), Kaneko Yoshinobu (Iori, Musashi’s adopted son, Part V), Nakamura Zekō (Zushi Nojisuke, a sword polisher, Part V), Hidaka Sumiko (Zushi’s wife, Part V), Satomi Kōtarō (Lord Hosokawa, Part V), Uchida Asao (Kakubei, Part V), Ogata Shinnosuke (Kumagoro, Musashi’s ally, Part V), Tamura Takahiro (Yagyu Tajima, Part V), Nakamura Kinji (Sir Hojo, swordmaster to the Shogun, Part V), Kita Ryūji (Sir Sakai, Part V), Kataoka Chiezō (Nagaoka Sado, Part V)4 |

| Status | Extant |

| Photography | Color (Eastmancolor) |

| Ratio | 2.35:1 |

| Format | 35mm |

| English Subtitles | Yes |

| Release Dates | Part I: May 27, 1961; Part II: November 17, 1962; Part III: August 14, 1963; Part IV: January 1, 1964; Part V: September 4, 1965 |

| Lengths | Part I: 110 mins.; Part II: 107 mins.; Part III: 104 mins.; Part IV: 128 mins.; Part V: 121 mins. Total running time = 570 mins. (9 hrs., 30 mins.) |

| Awards and/or Festival/Retrospective Screenings | None on record |

Note: Because of the extreme length of this five-part work, which may be the second-longest non-documentary film ever released theatrically in Japan,5 I’ve taken an approach that is different from any Uchida film previously reviewed, including the Sword in the Moonlight trilogy, which is to include a synopsis followed by a commentary and analysis for each of the five parts consecutively, rather than composing a complete synopsis first, followed by a very long review.

However, I strongly urge those readers who have just discovered this website and are starting to explore Uchida Tomu’s body of work not to read this review first. I advise this not just because of the review’s length, but because I don’t find this series of films very representative of Uchida’s work as a whole, and have much fault to find with some aspects of it. I suggest that the novice reader start with my review of Uchida’s classic comeback film from 1955: A Bloody Spear at Mt. Fuji, the very first review I composed for this site.

Having fought on the losing side during the historic Battle of Sekigahara (1600 A.D.), a young impoverished samurai from the village of Miyamoto named Shinmen Takezō crawls through the mud like an animal.6 His wild-eyed demeanor makes him appear even less human.

Takezō and his seriously-wounded friend, Matahachi, who is also from his village, are sheltered by two mercenary women, scavengers who rob samurai corpses: Okō, the widow of a bandit, and her informally adopted “daughter,” Akemi. While hiding in the women’s barn, Matahachi fantasizes about Otsu, his fiancée, playing the flute against a background of mountains. Back in the village, Takezō’s older sister, Ogin, is berated by Matahachi’s elderly mother Osugi (known as Obaba, the formal term for “old woman”), because Takezō had persuaded her son to leave and go to war against her wishes.

Okō cures Matahachi by literally sucking the infection out of his wound. While she seduces Matahachi, Takezō grows closer, platonically, to Akemi, though he still distrusts her. When Matahachi and Takezō are away from the house, bandits arrive, tie Okō up and search for stolen goods.

Takezō returns to the house and takes on all the bandits with a single wooden sword. His fighting displays no technique or finesse, but with sheer energy and bravado, he defeats them all. The leader of the gang, Tenma, tries to escape on horseback, but the ronin catches up to him and brutally beats him to death, and he delights in this murder.

Meanwhile, Okō, fearing that Tenma will revenge himself on her (not knowing that Takezō has already killed him), persuades Matahachi to abandon his friend and escape with her and Akemi. Thus, when Takezō returns, he finds, to his shock, a deserted house.

Back in the village, Otsu has a humorous conversation with her friend, the local Buddhist priest, Takuan. Despite a government reward being offered for the capture of fugitives from the recent battle, Takezō manages to sneak into the village. An official named Aoki warns the villagers that Takezō is a wanted man and that anyone giving shelter to him will be severely punished.

Aoki tells Obaba that Matahachi died in battle. The shocked and furious Obaba whispers to the commander her plan to capture their mutual enemy, Takezō. Meanwhile, Aoki’s men arrest Musashi’s sister Ogin and capture Otsu.

Takezō locates Obaba and informs her, to her shock, that Matahachi is alive and well and living with a woman in another province. He urges the old woman to inform Otsu of Matahachi’s survival. Obaba with feigned kindness offers him a meal, but suggests that he take a bath first.

Obaba summons Aoki’s men and they approach the bath. Realizing he’s been tricked, Takezō escapes the bath and brandishes his sword against the men. He climbs up on the rooftop, out of reach of his pursuers. Aoki, standing on the ground below, informs him that Ogin is being held hostage, but if he comes down and surrenders, she will be released. Not believing him, the samurai brags that he will rescue her instead, and escapes.

Otsu receives a message from Matahachi and Okō, who are living together, begging her to forget him. Takuan tries to comfort her, but she is inconsolable.

The lustful Aoki asks for Otsu to serve him sake and she reluctantly complies. Before he can assault her, Takuan intervenes, threatening to inform Aoki’s superior of his failure to capture the rogue samurai Takezō. Takuan then promises Aoki that, with Otsu’s help, he will take the ronin prisoner within three days, at the risk of forfeiting his own life if he fails. However, this promise is on the condition that, if successful, he will be allowed to handle the captive as he, Takuan, sees fit. Aoki is forced to agree.

Takuan and Otsu journey into the mountains together and set up camp. At night, Takezō wanders like a hungry animal into their campsite. After the starving ronin greedily consumes two bowls of food offered by the priest, Takuan says that he will now capture him “with the rope of dharma,” which is kinder than the laws of men, but Takezō angrily refuses. Takuan, however, points out that his sister Ogin is still a prisoner, and this seems to bring him to his senses at last.

Takezō, hogtied and in Takuan’s custody, is brought back to Miyamoto Village. The priest, as per his agreement with Aoki, decides that the samurai should be tied to the 1000-year-old cedar tree in the village square and left to rot until birds pick out his eyes. Takezō is hoisted up into the tree, much to Otsu’s distress.

During a savage rainstorm, Takuan urges Takezō to see the error of his ways before his death, but the latter shows only hatred and contempt for the priest who “tricked” him. Otsu, by now totally in love with the prisoner, accuses Takuan of heartlessness. After several nights of this punishment, Takezō is taunted by Takuan, who points out that the swordsman is no better than an animal. The ronin finally grasps his sordid, pathetic condition and bursts into tears.

In the middle of the night, Otsu climbs a ladder up the cedar tree. To Takezō’s astonishment and joy, she cuts the rope attaching him to the tree. The two escape together.

At Nakayama Pass, Takezō decides to split up with Otsu so he can rescue his sister Ogin from the prison at Hinagura, where he has heard she is being held. Otsu promises to wait for him at the Hamada Bridge in the castle town of Himeji for a thousand days, if necessary. He in turn promises to meet her eventually at the bridge.

Takezō, now alone, climbs down a steep, rock-strewn slope to the site of the prison at Hinagura. However, he finds it totally abandoned, with only a few empty, ramshackle huts left behind, as he desperately calls his sister’s name.

Otsu arrives at the Hamada Bridge but collapses with a fever. She is taken in and cared for by a kindly bamboo seller who lives by the bridge. Takuan, sitting nearby in a pilgrim’s cloak and hat, unrecognized, witnesses her arrival.

At a crossroads, Takuan again meets Takezō, who has disguised himself with a cloak of bamboo, like a wan scarecrow. Takuan claims that he acted as he did when he took the swordsman prisoner because it was the only way to save him from Aoki, but Takezō is unconvinced. However, the priest informs him that, if the fugitive will follow him, he will take him to where his sister Ogin is. The ronin, hungry and homeless and having little choice, obeys.

The priest leads him to Shirasagi Castle, where an ancestor of Takezō’s once served as lord. Though Aoki is still searching for Takezō, the present lord of the castle grants Takuan’s request to sequester him for the time being in a remote room there.

In the ominously dark room, Takuan points out that the dark spots on the walls that shine “like lacquer” are in fact the blood stains of Takezō’s ancestors in the Akamatsu Clan, who lost this castle. The priest informs the fugitive that this bleak place could be either a “pit of darkness” or a “tower of enlightenment” for him, depending on what he makes of it. Takuan departs, leaving Takezō alone with the many books in the room.

Takezō then sees, in a vision, fresh blood pouring down the pillar and walls, and hears the cries of horses and of soldiers from long-ago battles. Giant ghostly figures representing his ancestors urge him to purify their blood with the light of wisdom, and disappear.

In the following spring, Takezō, having read all the numerous books in his room, finally realizes that his previous courage had not been true courage at all. He makes a promise to himself to “uphold life as precious… and treat it kindly.”

Irie Wakaba is the actress daughter of Irie Takako, a major movie star of the silent era: Uchida Tomu had been a major enabler of the careers of both mother and daughter. Takako had performed in the late 1920s in several plays where she had been noticed by Uchida, who signed her to a contract with his then-studio, Nikkatsu. She appeared in the early Uchida comedy The Miserly Millionaire (Kechinbo choja, 1928, lost) and in his critically-acclaimed leftist satire A Living Puppet (Ikeru ningyō, 1929, lost). By the early 1930s, Takako had become so popular that she started her own film production company, Irie Productions, the first Japanese actress ever to do so. Takako’s daughter Wakaba, born in 1943, had begun to model for magazines in her teens in the early 1960s when her face caught the eye of Uchida, who had no idea, at first, that she was the daughter of the woman that he had helped make a celebrity over thirty years before. He cast Wakaba, age 18, in the leading female role, Otsu, in the first installment (1961) of his epic Musashi chronicle. After appearing in all five films of the series, she became a freelance actress and frequently appeared on television. In 1982, she returned to the cinema to appear in Ōbayashi Nobuhiko’s I Are You, You Am Me, aka Exchange Students (Tenkōsei), beginning a long-running collaboration with that director. Other films she made for Ōbayashi include The Girl Who Leapt Through Time (Toki o kakeru shōjo, 1983), in which she co-starred with her mother, The Discarnates (Ijin-tachi to no natsu, 1988) and Beijing Watermelon (Pekin no suika, 1989). In 2017, she appeared in Ōbayashi’s penultimate film prior to his death, Hanagatami – her most recent film credit.

Naniwa Chieko was a character actress, best known for her film work in the 1950s and 1960s. Born in 1907, her stage surname, “Naniwa,” was the ancient name for the city of Osaka, her hometown. Due to poverty, she started working to help support her family at the age of eight, and ten years later she joined a theater troupe. In the mid-1920s, she began her career in films, but left after only a few years, partly due to unpaid wages. From about 1930, she concentrated on the theater, forming a long-term partnership with her husband, a prominent actor and playwright, but left him and their troupe in 1951 when she discovered that he had had a child with a younger actress in the same company. Intending to retire from show business, she was nevertheless sought after by a radio producer, and in 1952 began a successful career in radio comedies, including the long-running series, “My Dad Is a Good-Natured Man,” playing the mother of a very large family. At about the same time, after having resumed her film career, she appeared in Mizoguchi Kenji’s Gion Festival Music, aka, A Geisha (Gion bayashi, 1953), for which she won Best Supporting Actress at the annual Blue Ribbon film awards. (She would also be cast in three other films by Mizoguchi, including Sanshō the Bailiff (Sanshō Dayū, 1954).) Naniwa went on to appear in a great many films for distinguished directors, including Kinoshita Keisuke’s classic Twenty-Four Eyes (Nijūshi no hitomi, 1954), Shimizu Hiroshi’s Sound in the Mist (Kiri no oto, 1956), Kurosawa Akira’s famous Throne of Blood (Kumonosu-jō, 1957), in which she played the old Ghost Woman, Ozu Yasujirō’s Equinox Flower (Higanbana, 1958) and The End of Summer (Kohayagawa-ke no aki, 1961), and Masumura Yasuzō’s The Wife of Seishū Hanaoka (Hanaoka Seishū no tsuma, 1967). Prior to the Musashi series, she had been cast by Uchida in a small but memorable role as a brothel employee in Chikamatsu’s Love in Osaka (1959). She died in 1973 at age 66, after having appeared in over 150 films. In the following year, she was posthumously awarded the Order of the Sacred Treasure by the Japanese government.

Satō Kei was a prolific character actor in the latter part of the 20th Century. He made his film debut in 1959 in Part Two of Kobayashi’s antiwar trilogy, The Human Condition (Ningen no jōken), in which he played a sympathetic friend of the hero. However, in the vast majority of his subsequent films, he portrayed villainous characters. He was a particular favorite of Ōshima Nagisa: Satō worked on sixteen films for that director, from his second feature, Cruel Story of Youth (Seishun zankoku monogatari, 1960) to his final movie, Taboo (Gohatto, 1999), nearly forty years later, for which he served as the film’s narrator. For his performance as the patriarch in Ōshima’s The Ceremony (Gishiki, 1971), Satō won the Kinema Junpo Award for Best Actor. Occasionally, he would branch out from his stereotypical villain roles, for example in Onibaba (Shindō Kaneto, 1964), in which he played an impoverished deserter who is desired by the film’s young heroine, or in Misumi Kenji’s Devil’s Temple (Oni no sumu yakata, 1969), based on a Tanizaki play, in which he effectively portrayed a devout Buddhist priest tempted and destroyed by an evil woman. In 1981, Satō appeared in Daydream (Hakujitsumu) – renegade director Takechi Tetsuji’s remake of his pioneering 1964 softcore “pink” film of that name – in which an anesthetized female patient fantasizes about being sexually abused by a dentist played by Satō. The sexual acts performed in the film were unsimulated (though images of genitalia and pubic hair were fogged in accordance with Japanese censorship laws), making this the first Japanese hardcore movie to be given a mainstream theatrical release, and it was a major box-office success. The actor continued appearing in films until a year before his death from pneumonia in 2010 at age 81.

(Continued on Page 2)

[…] The Miyamoto Musashi Series (Miyamoto Musashi, Parts I-V, 宮本武蔵), 1961-1965 January 9,… […]