Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

(Continued from Page 3)

After Musashi’s victory over Seijurō of the Yoshioka School (see Synopsis, Part III), Seijurō is brought back to the dōjō by his students on a wooden gurney, the stump of his left arm bleeding where Sasaki had chopped it off (at his own request). His younger brother, Denshichirō, chastises him for “whining” and his uncle, the elder Mibu Genzaemon, insists that he commit seppuku with his remaining good arm. Denshichirō sends the students out to hunt for Musashi.

Seijurō passes all responsibility for the school onto his younger brother, but begs him not to hold a revenge match against Musashi, as, in his opinion, he lacks the skills necessary to defeat him. The latter is outraged by this suggestion and calls his older brother a loser and a coward. To the entire school, Denshichirō vows to revenge their lost honor by defeating Musashi. Meanwhile, a student arrives to announce that they had found out that Musashi is staying with the calligrapher Hon’ami Koetsu and his elderly mother in Kyoto.1

Denshichirō discovers that Seijurō, out of shame, has run away, much to his younger brother’s disgust. Hayashi, Seijurō’s most loyal aide, appears and admits to having helped the former Young Master escape. He advises Denshichirō to proceed cautiously and study Musashi’s style before fighting him. The new Young Master is outraged by this “cowardly” advice and banishes Hayashi from the clan, to the latter’s dismay.

In Kyoto, Koetsu asks Musashi if the latter would like to accompany him to a “house of mirth” (that is, a geisha house), to which he has just been invited by his friend, the coarse merchant Haiya Shoyu, and the ronin agrees to go. As the swordsman and Koetsu approach Haiya’s house, three men from the Yoshioka School give Miyamoto a written challenge from Denshichirō for a duel to take place near the Renge’o-in temple that very night. He accepts the challenge.

At the geisha house, Haiya decides that only the tayū (highest-ranking courtesan) Yoshino is worthy of entertaining Musashi. Though drunk, Haiya, with Koetsu and the ronin in tow, goes in search of her and finds her entertaining a rich patron. The swordsman, slipping away from the party, exits through the garden.

During a snowstorm, Denshichirō arrives at a lot next to the temple well before his adversary does. He drinks a great deal of sake to strengthen his resolve. The elder Mibu arrives and is reassured by Denshichirō’s presence. Just as Seijurō had done, the new Young Master orders his underlings not to assist him in the battle, and everyone leaves the area but Denshichirō.

Musashi suddenly appears, standing on the high porch surrounding the temple, about five or six feet above ground level. Denshichirō scolds Musashi for being late and demands that the ronin come down to ground level, and he agrees, but doesn’t change his position, much to Denshichirō’s confusion. Two of the Yoshioka students, disobeying their master’s orders, approach Musashi from their hiding place underneath the porch. One of these students suddenly emerges and tries to stab Musashi, but the ronin easily kills him and the other student, and mortally wounds Denshichirō before making his escape. Mibu vows that his nephew’s death will not be in vain.

Returning to Haiya’s party at the house of mirth, Musashi accompanies the group to the tayū Yoshino’s modest “tea room” nearby. Instead of feeling elated after having survived that night’s duel, however, Miyamoto appears taciturn and pensive.

Yoshino performs a sad song on the biwa – a four-stringed, lute-like instrument, played with a plectrum (bachi), rather than with fingers. Later, the geisha, after receiving a warning that the whole Yoshioka School intends to attack Musashi to revenge the death of their leader, manages to manipulate the young ronin, with Koetsu’s connivance, into agreeing to stay overnight. Yoshino and Musashi are left alone in the house.

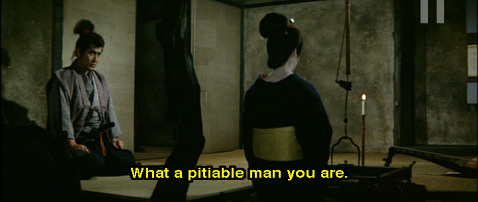

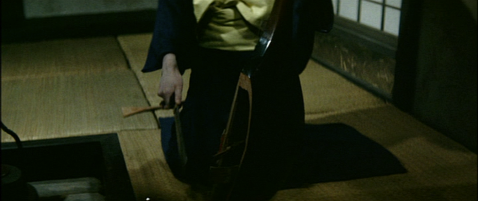

Yoshino surprises and angers the swordsman by calling him “a pitiable man,” pointing out that he lives in constant fear of his enemies and that he will eventually be killed by one of them. Musashi attributes her words, which he thinks foolish, to the fact that she is “only” a woman and doesn’t understand the samurai’s code. She doesn’t back down, however, but compares the ronin unfavorably to the biwa she had just played, an analogy Musashi fails to grasp. To illustrate, she picks up the same knife she’d been using to cut firewood, and smashes to pieces the front of the instrument, exposing its hollow body, to Musashi’s amazement.

The tayu points out that the biwa is able to produce such a wide variety of sounds, despite having only four strings, because of the soundboard within it and because of the subtle curves carved into its body, which give it flexibility. If the instrument were as unbending as Musashi himself, she says, it not only would be unable to produce such resonant sounds, but the strings would break if she tried to pluck them. Thus, the inflexible ronin will surely, sooner or later, break under the strain of defending his life against so many enemies. Musashi, at a complete loss for words, simply bows his head, ashamed.

The following morning, the ronin is reunited with the boy Jotarō and ventures into town, only to find the streets filled with the students, bent on revenging their disgrace. Jotarō is frightened, so Musashi allows him to escape by helping him climb over a fence at the end of the street.

Musashi returns to the gang of students. He declares himself ready to fight them, but insists that to engage in a duel now, right there in the street, would only be disturbing the peace. He asks the students whether this is a grudge match or an actual challenge. The leader of the students, Otaguro, scornfully denies that it is a grudge match. Why then, the ronin asks, have they not officially challenged him, as both Seijurō and Denshichirō had done?

The two sides are about to clash when Sasaki suddenly appears. He agrees with Miyamoto, claiming that without an official challenge, a duel between the two sides would bring dishonor upon all warriors. Otaguro, on behalf of the school, challenges Musashi to a duel two days hence, at Eizan Road at the foot of the Ichijō-ji Mountain, at the Sugari-matsu pine tree. The ronin agrees to these terms. The following day, the elder Mibu, contradicting what was agreed upon, decides that the heir to the Yoshioka clan – his son Genjirō, a boy of about nine-years-old – will attend the duel in person to represent the clan.

At an inn on the night before the battle, Musashi is confronted by Hayashi, the excommunicated Yoshioka student, who asks of him what grudge could he possibly bear against the Yoshioka School, which had done him no harm prior to his initial challenge? The ronin replies that his actions are dictated by his “martial arts path,” from which he cannot deviate. Hayashi points out that because of that path many people have died and will die, possibly including Musashi himself, and asks what the point of it all is. The ronin rudely answers, “I don’t know,” and accuses him of “talking drivel.”

When finally Hayashi asks what exactly he is trying to gain from his quest, the swordsman angrily declares, “The sword is utterly merciless. The sword is seeking that which is ultimate. It is without compassion.” Because Hayashi is a mere “bystander” in his conflict with the Yoshioka, the ronin orders him to get out of his way, and leaves.2

On his way to the dueling site, Musashi sees Otsu in the woods playing the flute. She greets him and reveals that she knows all about the upcoming duel. The young woman informs him that she’s ill and that if he dies, she’ll have no reason to go on living. The swordsman apologizes to her for his coldness and declares his love for her. He claims that there hasn’t been a day when he hasn’t thought of her, but that he is torn between the worlds of love and of asceticism. She asks if she could be his wife. He embraces her and commands her to go on living even if he dies, then continues on his way.

At dawn the following day, Musashi has situated himself in the woods far above the Sugari-matsu pine, and watches as the Yoshioka School swordsmen, along with Mibu and the child Genjirō, arrive at the dueling site, at which a rice paddy is located. Men with guns are situated at the tops of trees surrounding the area to protect the clan. The ronin creates a map of the relative positions of all the students and tries to figure out where and when to most effectively attack them.

Sasaki unexpectedly arrives and declares that he wishes to serve as a witness to the duel, but since neither the Yoshioka clan nor Musashi had granted prior permission to his filling any such role, Otaguro indignantly refuses his request. Sasaki retreats to a position some distance away, where he amiably greets Hayashi, who has also come to observe the event.

Musashi quickly and silently descends from the hill, throwing small knives at the gunmen to knock them out of the trees. He attacks ferociously with both swords the bodyguards surrounding Mibu and Genjirō. Mibu panics and tries to shield the boy, but Musashi, with one thrust of his sword, impales both the father and the son, killing them both at once. Hayashi, maddened, declares the ronin to be a “demon,” and joins the fight on the side of the school that had excommunicated him, much to Musashi’s horror.

Miyamoto kills most of the Yoshioka swordsmen, including Otaguro. Finally, the only one pursuing him is Hayashi, though the ronin had begged him not to get involved. The two men slip, slide and crawl through the wet paddy fields. Finally, the ronin slashes his pursuer’s face, blinding him. Musashi is appalled by what he has done and runs away.

Sometime later, Miyamoto, with several weeks’ growth of beard, is sitting on a porch at the Enryaku-ji temple on Mt. Hiei outside Kyoto, carving a Buddha statue. A group of monks appear, all but one armed with spears, and order him to leave the mountain immediately. The ronin is confused, as the temple officials had given him permission to stay. The monks inform him that his “evil reputation” has led to his banishment from the holy mountain, and they angrily call him “heretic,” “devil” and “demon.”

Musashi accepts the temple’s decision to evict him, but refuses to tolerate their insults, claiming that he had fought the Yoshioka clan honorably and had nothing to be ashamed of. The leader of the monks reveal that it was his killing of the child Genjirō that led to the decision to banish him. Musashi, guilt-stricken, offers no further reply to their insults.

The monks leave. To himself, Musashi justifies his killing of Genjirō and blames the little boy’s death on the Yoshioka clan. He finishes carving the Buddha statue and sits contemplating it.

This episode reintroduces the character of Denshichirō, younger brother of Seijurō, the former head of the Yoshioka School, who had been forced to abdicate after the disgrace of losing (and losing his arm) to Musashi in their one-sided duel at the conclusion of Part Three. At the beginning of that earlier installment, Denshichirō had attempted to challenge the elderly Sir Yagyu to a match, but succeeded only in offending him. Throughout this and other such incidents, the vain Denshichirō was utterly oblivious to his folly, absurdly regarding himself as better – smarter, braver, stronger, more skilled – than everyone around him, including the patriarch and Musashi.

In Part IV, Denshichirō is, if anything, even stupider and more obnoxious than he was in Part III. (Hira Mikijirō is very effective, though less than subtle, in this thankless role.) After his older brother Seijurō returns wounded from his duel, the Younger Master accuses almost everyone around him of cowardice, even Seijurō himself, to whose authority he would normally be expected to defer as a younger sibling. Oddly, none of the disciples point out, even amongst themselves, that Denshichirō had refused, until the very last minute, to join his brother in his fight against Musashi, and that therefore he is the real coward.

When the faithful Hayashi, whose one and only goal is to preserve and protect the dōjō, points out the obvious – that to defeat Musashi, one must carefully study his style and plan a strategy to counter it – Denshichirō not only rejects this commonsensical advice, but declares Hayashi excommunicated (hamon) from the dōjō. It’s quite obvious from the start that Musashi will easily defeat such an overconfident, foolish and unworthy foe, so Uchida in these scenes generates absolutely no dramatic suspense.

The duel between Musashi and this character in the first half of the film is therefore perhaps the most perfunctory and disappointing in the entire series. Even the battle on Hannya Hill at the end of Part Two contained an interesting twist, when the monks, whom Musashi had assumed were allied with the ronin against him, suddenly turned on their real foes: the ronin themselves. In this episode, when Musashi suddenly appears on a high porch surrounding the Renge’o-in temple, giving him the advantage of the high ground over Denshichirō, we would naturally expect the latter to climb onto this porch to neutralize his advantage. But it never seems to occur to the man to do so, even though a set of stairs leading from the ground to this porch is clearly visible.

We may reasonably infer from this that the new Young Master’s drunkenness prevents him from thinking straight. Earlier, Musashi had told the assembled guests at Haiya’s party that he was refraining from sake because it made him sleepy, which the others had assumed was a mere joke. But his refusal to drink alcohol, keeping himself alert and his reflexes in fighting trim, gives him yet another advantage over his adversary, who had inanely remarked about sake, of which he had consumed a great deal prior to the fight, “There’s no ally better than this.”

Now the filmmakers, it seems to me, are perfectly correct in condemning the bogus masculine ideal epitomized by the incompetent macho braggart Denshichirō. My big problem with this character, however, is that he ruins Musashi’s dramatic arc. It would be perfectly appropriate for the wandering ronin to battle mere thugs and fools like him early in his training, in the first couple of films in the series. But for a proper narrative progression, I believe that the hero should have gradually taken on more formidable and impressive enemies, until his destined encounter with his greatest foe of all, Sasaki Kojirō, in the final installment. But since Denshichirō poses even less of a threat to the protagonist than his weak and neurotic older brother, there seems to me no honor at all in Musashi’s pointless victory – though the scene is, typically, very well-staged by Uchida.

This film contains one of my favorite scenes in all five parts of the Musashi series, perhaps my absolute favorite scene in the series. On a snowy night, the hero briefly leaves a party in Kyoto given by the vulgar merchant Haiya in order to duel Denshichirō. Immediately after this victory, he escapes and returns to Haiya’s party, where he is entertained by the beautiful geisha, Yoshino. When he is left alone with her, however, she, instead of trying to charm him, upbraids him, calling him “pathetic” and in essence condemning his futile, fatal way of life.

This exchange is very significant because it represents a rare defeat for Musashi in a war of wills, something no other character except the monk Takuan, not even Sasaki Kojirō, manages in the course of the series. And yet Yoshino is being cruel to be kind: her goal is to save the ronin from certain death. This female character is so utterly different from the weepy Otsu and Akemi or, for that matter, the lascivious and larcenous Okō that she seems to have wandered in from a whole other movie entirely.3

Unlike those other women, the tayū fits neither the “good girl” nor the “bad girl” template of Japanese film heroines. Rather, this geisha, despite her profession, proves as stern and unyielding as a samurai. She refuses to let Musashi intimidate or patronize her, even going so far as to destroy her own (presumably expensive) biwa to teach the ronin a lesson for his own good, the truth of which he is forced, at last, to acknowledge.

One is often delighted, in a film released during Japan’s Golden Age, to encounter a memorable performance by a little-known actor. It’s quite impressive, this array of talent that the major studios could draw upon during this remarkable era. In this case, the obscure actress who plays Yoshino is Iwasaki Kaneko (born 1932). Iwasaki – who, amazingly, is still alive as of late 2024, sixty years after this film was released – in her long career never became a movie star, perhaps because she preferred the stage to films. And, unlike many Japanese character actors, she doesn’t even have her own English Wikipedia page, though she does have a Japanese one. Yet her work in this movie is stunning. She even appears to be playing and singing the song on the biwa herself, without dubbing.4

When Musashi and Yoshino are left alone together, Uchida creates a remarkable dramatic tension between the two characters, which he subtly intensifies throughout the scene by visual means. There’s certainly a sexual element in this tension – Yoshino is a very attractive woman – but that’s only one element of it. Essentially, she’s calling into question Musashi’s heroic identity, and the latter reacts at first with rage and denial, then with astonishment, and finally with resignation, accepting her superior wisdom. One might be tempted to call this wisdom “feminine,” but in fact neither Otsu nor Akemi possesses it, and neither of those ladies, both in their different ways in love with Musashi, would even dare to talk to him in this way.

When Yoshino mentions the danger he faces from the Yoshioka School and calls him “a pitiable man,” the focus is all on the ronin, whose face is fully visible; her face is turned away from us and cannot be “read.” Uchida cleverly places a narrow, somewhat crooked tree trunk – an architectural element of this rustic house – between them, thus dividing the room vertically into two uneven spaces, hers and his, making visually explicit the philosophical divide between them.

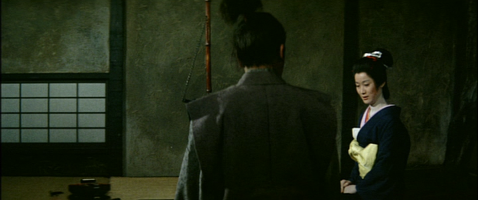

After he pushes back against her judgment of him as “pitiable,” we see her face, looking like a Noh mask, in a close, semi-profile shot against a neutral background. Unintimidated, she refuses to back down, but rather sharpens her attack. “Perhaps it could be said that death is written all over your countenance,” she tells him.

Next we see a close shot of the infuriated Musashi, who thinks she is belittling his fighting skills. He looks as if he is about to strike her, which is extraordinary, as he had never before raised his hand in anger against any woman, even Obaba, who had several times tried to murder him. Then, when he shifts his position slightly to confront her, Uchida in turn moves the camera so that she re-enters the shot in the foreground, her face only partly visible, as she deftly parries verbally all his objections.

There follows a matching over-the shoulder shot from behind Musashi (that is, a reverse shot). Yoshino smiles enigmatically as she compares him to her biwa, much to the ronin’s bewilderment.

At this point, Uchida executes a very complex camera movement: without a cut, he slowly pulls the camera back so that Yoshino is now on the right-hand side of the frame rather than the left; Musashi, rather than being situated at the right of the frame, is now in the center; and the biwa is seen lying on the floor on the left-hand side. The space is thus now divided vertically into three… as if the musical instrument were a third person in the room.

Then, as Yoshino continues to speak, the camera slowly tracks in to a medium shot of the biwa, so that both characters are now completely out of the frame. This allows the audience a few moments to fully contemplate and admire the beauty of the instrument.

Yoshino then re-enters the frame, with only her legs and feet visible at first, and picks up the biwa, bringing it over to her corner of the room. She attacks it with a knife, shattering the front of this gorgeous object, irreparably destroying it – the second most-shocking act of violence in this very violent film.5

After a cut, the next shot slowly settles into a static medium two-shot of Yoshino and Musashi. She then explains why he, unlike a biwa, is much too rigid and inflexible, and thus will eventually be killed, unless he musters the will to change.

The Musashi series was, of course, adapted from a novel, not a play. But for more than half-a-dozen years prior to this film, Uchida had been devoting a large part of his creative energy to filming adaptations of classic stage plays, re-affirming his love of theater. Thus, he allows the remainder of this crucial sequence to play out as if it were being performed on a stage, trusting his actors to convey the characters’ complex emotions all the way to the scene’s fadeout, without a cut.

It’s rather as if Uchida were asking himself in this scene, through the character of Yoshino: “what, after all, is a man, and what is a man even supposed to be?” – a perfectly valid question, less than twenty years after the Japanese nation, and thus Japanese manhood, were defeated in a major war. And as Yoshino’s harsh judgment of Musashi makes clear, any honest answer would necessarily be much more complicated and painful than most movies at that time would ever have permitted.

The Musashi pentalogy is probably the most overtly commercial project Uchida worked on in his entire postwar career, and it must be admitted that some of it is very pedestrian indeed, especially by Uchida’s standards. So I’ve described this scene at some length to prove that even in the context of such a project, the magic of which this unique filmmaker was so often capable is never totally absent. This is particularly true in scenes such as this one, in which the director appears to have most heavily invested himself emotionally.

One last note: over Yoshino’s long concluding speech, Uchida has dubbed, very subtly, almost subliminally, the echoing sounds of a biwa. It’s as if the ghost of the musical instrument Yoshino had just destroyed defiantly continued to play after its violent “death.” It’s a brilliant, masterful detail.

(Continued on Page 5)

[…] The Miyamoto Musashi Series (Miyamoto Musashi, Parts I-V, 宮本武蔵), 1961-1965 January 9,… […]