Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

(Continued from Page 4)

The big “set piece” in this installment of the series – which is also, except for the final battle with Sasaki in Part Five, the most important one in all five films – is the climactic battle in the rice paddy near the pine tree, in which Musashi single-handedly takes on the entire population of the Yoshioka dōjō: seventy-three against one. (It’s not clear to me if the little boy, Genjirō, counts as one of the seventy-three, though he’s certainly treated as fair game.) This complicated scene, as executed by Uchida, is not quite as silly as it sounds, but it’s still a bit silly. It’s also quite nasty in an unexpected way, as I shall discuss.

The sequence opens with the field shrouded in mist, the color of the image seemingly drained to a green monotone, with, on the soundtrack, eerie organ-and-clarinet music that sounds as if it belongs in a horror movie, which will later come to seem perfectly appropriate. Musashi watches his foes arrive at the site from his hidden vantage point in the woods high above the fields. When the Yoshioka men finally gather near the big pine tree and begin to debate strategy, speculating as to which of the three roads Musashi might make his appearance, the big mystery is why none of these supposedly intelligent warriors is able to figure out that their nemesis might already be there, observing them from above. As often occurs in this series, an implied aura of genius is dubiously conferred by the filmmakers upon Musashi’s quite unremarkable tactics, which nonetheless baffle his less-than-brilliant opponents.

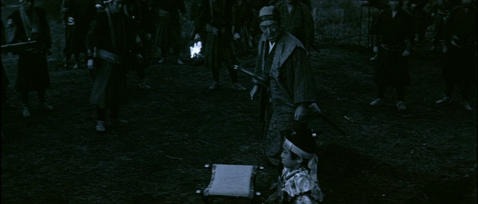

There follows a very moving shot of the innocent young boy from the Yoshioka clan, Genjirō, looking scared and being comforted by his father Mibu, who tells him that, since he will be not be participating in the fighting, he is safe and has no need to be frightened. The child sits, ramrod-straight, like a loyal soldier, on the chair from which he will observe the struggle, and Mibu compliments him on his brave spirit. The viewer may be uncomfortably reminded at this point of the similarly conscientious Jotarō, whom the boy slightly resembles.

Like the logistically-obsessed heroes in a Kurosawa film such as Seven Samurai, Miyamoto in his hiding place draws up a map depicting the terrain and the forces arrayed against him. Suddenly, he draws a line on the map leading to the spot representing the pine tree and remarks, “It’s kill or be killed.” This is followed by a shot of the boy Genjirō, and the astute viewer will realize what is about to happen.

Musashi descends from the hill, appearing as if from the sky, a sword in each hand, and makes a beeline for the little boy and the bodyguards around him. Mibu tries to shield the boy’s body, but Miyamoto with a single thrust impales both Mibu and Genjirō (after he exclaims that he’s “sorry”), and father and son, embracing in a final paternal “hug,” fall together to the ground, dead. It’s one of those shots in Uchida’s cinema in which the viewer can’t quite believe what he or she is seeing.

Musashi is probably correct in assuming that he can’t possibly survive the battle without striking at and destroying the Yoshioka clan’s symbolic leader, the school’s young heir. But just about every perpetrator of atrocities against civilians, up to the present day, has used “it’s kill or be killed” as an excuse, often conveniently overlooking the fact that they themselves were the aggressors in the first place, as in this case. And it’s very distasteful that the viewer is being asking to empathize with, for the rest of this installment and the concluding one, a child killer… and the fact that Musashi is later ridden with guilt over this crime does not begin to atone for it.

Having thus struck at the heart of the Yoshioka School, the swordsman proceeds to make mincemeat of the other students in his struggle to escape alive. The impressively worked-out swordfight choreography – with Uchida doing his best to make it all seem spontaneous – and the use of a handheld camera to enhance the kinetic power of the sequence almost makes this situation credible.

Musashi is finally confronted by Hayashi, the former Yoshioka student that had been declared hamon (excommunicated) from the dōjō, who seems to have been driven mad both by Musashi’s savagery and the absurdity of his own situation. Calling the ronin a “demon,” Hayashi draws his sword against him, and the latter, desperate not to fight a man against whom he has no quarrel, runs from him as if from a ghost. Finally, in a desperate attempt to stop Hayashi in his tracks, Musashi slashes his face with his sword, blinding him. Both the ominous music on the soundtrack and the terrified expression of the “hero” underscore that this is a transgressive act, a violation of all acceptable samurai norms.

It should be noted that, in Japanese cinema, such scenes depicting solitary battles by lone samurai against seemingly innumerable opponents had long been a convention of jidai-geki films, going back to at least the 1920s. The 1925 film Orochi [Serpent] (director: Futagawa Buntarō), starring period-film superstar Bando Tsumasaburō, concluded with a legendary battle in which Bando’s character takes on an entire town, which believes, wrongly, that he is a criminal. Uchida himself, of course, had filmed, decades later, a similar scene, much more realistically, in Hero of the Red-Light District. But the big difference between all those earlier films and this one is that almost none of those almost superhumanly strong and energetic rebels managed to get away without being killed or captured, as Musashi does here.

This scene evokes not only previous works by other moviemakers, but past moments in the Musashi series and even of other Uchida films. When Hayashi and Miyamoto are crawling around in the rice paddy, their clothes covered with muck, the viewer will probably recall the very beginning of Part I, when Takezō and Matahachi lay like wild animals in the mud after their ignominious defeat at the Battle of Sekigahara. And when Musashi runs over the length and breadth of the field, sometimes in medium shot, sometimes in long shot, one is reminded of the scene in Earth in which the peasant Kanji – avoiding the law to keep from being arrested for the theft of his neighbor’s crops – runs from the foreground of the field to the extreme background in the same shot.

The comparison with Kanji is apt. Like that character, the ronin is a thief, though not of crops but of the lives of the dōjō students. And also like Kanji, he seeks to avoid any consequences for his actions.

The English writer, the late David Shipman, in his book The Story of Cinema, was one of the very few English-language film historians to even acknowledge the existence of Uchida, whose Hero of the Red-Light District he rightly praised.1 In another part of the book, he also discusses this particular installment of the Musashi series. (Strangely enough, he never alludes to the other four films of the pentalogy: perhaps he never saw them.) He seems far more impressed than I was by the seventy-three-against-one duel in Part IV, but he’s careful to add, “the action scenes apart, Uchida’s handling on this occasion does not seem worthy of the director of [Hero of the Red-Light District].”2

I agree with Shipman, for reasons that should be fairly obvious. Jirō, the protagonist of the 1960 film, is not a samurai but a mere merchant, incited to madness and murder by the humiliations inflicted upon him by a pair of pathologically greedy procurers. The fascination of that film lies in witnessing the extremes to which an ordinary man who has lost everything – or rather, who has had everything taken from him – can be driven. Musashi, on the other hand, is the antithesis of an ordinary man, and violence is his daily reality. The viewer would be astonished if he didn’t attack with lethal force his perceived foes, none of whom have injured or insulted the ronin.

The conclusion of this installment is far more interesting than those of the previous three. Having found refuge, after his victory over the Yoshioka, at the famous Enryaku-ji temple on Mt. Hiei outside Kyoto, the now-bearded Miyamoto is interrupted in his new pastime of carving Buddha statues by the arrival of a delegation of monks, who inform him in no uncertain terms that he must leave the mountain immediately. Musashi questions the fairness of this decision, as the temple officials had granted him permission to stay.

The leader of the monks admits this, but informs him that those officials later changed their minds after news of the ronin’s “evil reputation” (akuhyō) reached them. When the indignant swordsman replies that he fought honorably at Ichijyo-ji temple, the monk reminds him of the murder of the child Genjirō. This strikes a nerve, and from this point on, Miyamoto seems like a broken man, utterly unable to defend himself.

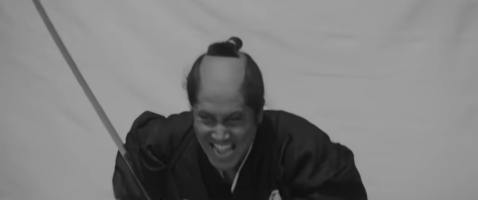

The transformation of Nakamura Kinnosuke as an actor in the few years since he first appeared in Uchida’s cinema in 1957 was impressive. As Hyōma in the Swords in the Moonlight films, he seemed the most normal and sane of young men, particularly by comparison with the trilogy’s tormented antihero, Ryūnosuke, played by Kataoka Chiezō. But already in Chikamatsu’s Love in Osaka (1959), it is Nakamura himself who portrays the tortured soul. And as the neurotic Musashi, Nakamura effectively embodies a solitary, paranoid man who is in many respects his own worst enemy. When the monks remind him that he has Genjirō’s blood on his hands, the ronin looks like he’s about to have a nervous breakdown.

Other directors would go even further than Uchida did in using Nakamura to embody the psychosis behind the “way of the sword.” In Imai Tadashi’s Revenge (Adauchi, 1964), released the same year as this film, his samurai protagonist goes, terrifyingly, all the way from neurotic tics and quirks into full raving madness. Even more disturbingly, Imai showed how this insanity follows logically from the inhumanity and absurdity of the samurai code itself.

The fact that there were almost no Hollywood stars of the mid-century period who would ever allow a director to mess with their image to this degree – Jimmy Cagney as the crazy gangster in White Heat (Raoul Walsh, 1949) is the only one who comes to mind – shows by contrast the admirable commitment of Japanese actors like Nakamura when it came to fulfilling the creative visions of the directors who employed them.

(Note: the film begins with a twelve-minute reprise of the narrative of the previous four installments of the series, ending with the final moments of the last scene of Part IV.)

Musashi, who had been banished from the holy mountain, Mt. Hiei, wanders alone through the countryside. Otsu follows Musashi in a rural area beside a raging river. The swordsman begs his beloved to forget him because he now has the blood of a child on his hands. Undeterred, she swears that she will always follow him, but never interfere with his training. He tells her he cannot love anyone, because the sword is all that matters to him now. He enters the river, placing himself under a waterfall in a ritual of purification.

Wandering once again in the countryside, Musashi comes upon a young boy sharpening a blade. The ronin discovers that the child’s father has just died and, as the boy is much too small to carry the body alone and has no one to aid him, he intends to cut it up to transport it to the gravesite. Taking pity on the child, whose name is Iori, Miyamoto helps him bury the dead man.

The ronin then resolves to assist the boy in farming the land, as he himself had been a farmer as a younger man. Though the villagers mock the pair for tilling such rocky soil, their efforts yield two bales of rice, a better yield than their neighbors expected. On the way to town to sell their crop, the swordsman and the boy encounter Nagaoka Sado, a retainer for the Hosokawa clan, who kindly asks after the boy’s father and is saddened to learn that he has died.3

That night, Iori spots a gang of mounted bandits galloping towards the village and notifies Musashi. The two ride off to confront them. The bandits attack the village’s main barn and steal the horses and crops, then torch the structure. The ronin arrives and beside the raging fire, on horseback, attacks the bandits on all sides.

Musashi and Iori set off on the road to Edo. On arriving at the capital, they enter the shop of a sword sharpener, Zushi Nojisuke, and the ronin offers his sword to be sharpened. Zushi’s wife recognizes their customer as the famous Miyamoto Musashi, and Zushi invites him inside. In the shop, the ronin sees the “washing pole” – the distinctive long sword of Sasaki Kojirō, which he had left behind for sharpening.

Sasaki sits in a room in Edo being entertained by a young woman, Omitsu, who is playing the koto. After she is finished, he smiles and takes her hand, intending to make love to her. When she resists because her uncle Kakubei, with whom she lives, will soon return home, he points out that Kakubei only pretends not to know that they’re already in a relationship.

Sasaki stops by Zushi’s shop to pick up the “washing pole.” He is angered that the proprietor hasn’t honed it yet, and decides to take it elsewhere. On reclaiming it, he recognizes a weapon that had been left behind to be sharpened as Musashi’s sword.

At Hangawara’s fencing school, Sasaki meets Obaba, who is training there. He reveals to her that Musashi, her enemy, is in Edo. The samurai suggests that she find out where Miyamoto lives by lying in wait outside Zushi’s shop for the ronin to retrieve his sword and then following him home.

During an archery contest at the court of Lord Hosokawa, Kakubei recommends to Nagaoka that Sasaki enter Hosokawa’s service. The retainer insists on meeting the young samurai first before making a decision. But when Kakubei relates Nagaoka’s message, Sasaki arrogantly refuses to meet with a mere retainer, and asks the embarrassed Kakubei to arrange a meeting with Lord Hosokawa personally.

On the appointed day, when Sasaki is brought before Hosokawa and informs the daimyō about the Gan-ryu style that he invented, the latter proposes a demonstration match with one of his men, Okaya. At Sasaki’s insistence, the man fights him with the blade of his spear exposed, while Sasaki himself wields a mere bokken (wooden sword). The two men duel and, despite Okaya’s overwhelming advantage, Sasaki prevails. Nagaoka proclaims it “a splendid match.”

Outside Zushi’s shop, Obaba and her allies in the Hangawara gang lie in wait as Musashi, accompanied by Iori, picks up his sharpened sword. The gang eventually brings Obaba to the inn where he is staying. She challenges Miyamoto to come down into the street to fight her, but he ignores them all.

Other men then arrive, bringing an invitation to Musashi from Sir Hojo, the Shogun’s swordmaster. Obaba insists to Sir Hojo’s messenger that her vengeance against the ronin must take precedence over any purpose for which Sir Hojo might want him. The messenger asks Obaba who in her family had been killed by Miyamoto, and she’s forced to admit that Musashi had never killed anybody in her family. The crowd laughs at her silly, pointless vendetta, and the Hangawara gang members are so embarrassed that they abandon their support of her quest.

At Sir Hojo’s residence, Musashi is reunited with his old mentor, the priest Takuan, and meets Sir Yagyu Tajima, Sekishusai’s son, who greets him warmly. He has been summoned by them to apply as a candidate to replace Sir Hojo as the Shogun’s swordmaster.

Several retainers of the Shogun debate the merits of Musashi’s proposed appointment. One of them, Sir Sakai, expresses major reservations about the ronin, because Miyamoto has, in his view, been “defiled” by the blood of the child he killed, Genjirō. Later, Sir Yagyu Tajima politely reports back to Musashi that the latter’s application has been denied. The ronin is clearly upset by this rejection and leaves without saying goodbye.

Musashi returns in winter with Iori to the pine tree near the temple where he had fought his duel with the Yoshioka clan. To his horror, he sees, at the base of this tree, a headstone bearing the image of father-and-son Buddha figures, commemorating the deaths of the Elder Mibu and Genjirō, both of whom he had killed on that fateful day. The ronin hears a tapping sound behind him and sees a blind monk whom he recognizes as Hayashi, the man he had insulted and then blinded, carving a figure into a headstone. The little boy cheerfully greets Hayashi, who appears to be insane, but the guilt-stricken Musashi gently pulls the child away.

Somewhat later, Kakubei reveals to Nagaoka, in the presence of Sasaki, that he had spotted Musashi in the backyard of the merchant Koetsu, for whom the ronin is now producing artistic works and performing odd jobs. Sasaki sneers at this, implying that the ronin’s behavior is merely a reaction to his having been rejected by the Shogunate. He calls Miyamoto’s humble lifestyle “the path of the loser.”

Nagaoka disagrees, calling the ronin’s sword “the sword of the heart.” Sasaki appears offended by Sato’s remark, as he believes that the sword is “power and technique; the distribution of these two aspects,” and thus the heart has nothing to do with it. When Nagaoka asks Sasaki if he’s “absolutely certain” he’s right, the latter suddenly requests that he be allowed to challenge Musashi to a duel. The skeptical Nagaoka asks if he’s sure he would win, reminding him of the consequences to the Hosokawa clan should he lose to the ronin. Sasaki smiles and replies that Nagaoka needn’t worry.

Musashi receives the official challenge by letter from Sasaki. The ronin tells the worried Koetsu that it was inevitable that he would have to fight the swordsman someday. Musashi informs the boy Iori that he will send him with a letter of recommendation to Nagaoka so that he can begin the process of becoming a samurai.

Lord Hosokawa discusses with Kakubei the location of the upcoming duel. The latter suggests that it should take place on the small island of Funajima.4 In this way, they would avoid the crowds of spectators that public interest in Musashi and Sasaki would otherwise inevitably attract. Hosokawa agrees with this plan.

The worried lord then asks Nagaoka what would happen to his fief if Sasaki were to lose the duel. Kakubei interrupts to assert that such an outcome would be “unimaginable.” However, he adds that whatever the outcome, the island is an isolated location, and that the clan members would “preserve the honor of the fief” no matter what – not-so-subtly implying that if Musashi were to win, they would kill him. Though Nagaoka is silent, this idea clearly doesn’t sit well with him. Later, alone with Lord Hosokawa, he admits that he doesn’t know which swordsman will win, but that the two should fight fairly for the honor of bushido.

Otsu reads the public placard on which the Musashi-Sasaki duel is announced and walks away in dismay. She comes upon a seated woman comforting a crying baby and realizes that she is Akemi. The latter recognizes Otsu, who learns from her that Matahachi, who has gone to seek milk for the child, is the infant’s father. Obaba approaches and, overhearing the conversation, realizes that the baby is her grandchild. Tears come to her eyes.

Matahachi arrives with the milk and sees Otsu, his former fiancée, who greets him cordially, without bitterness. They all spot Obaba nearby, who declares that she will “never accept” this grandchild. They approach the old woman, but she continues to cry out, “I won’t accept it.”

On the night before the duel, Kojirō is disgusted and unnerved that Kakubei has hired assassins to accompany him to the island for the duel, since these men would be totally unnecessary unless he himself were killed. He tells the weeping Omitsu that that outcome will never happen, but appears less than confident.

Sasaki, with Kakubei, Nagaoka and their huge entourage, set out in boats in the middle of the night for Funajima Island to wait there until Musashi arrives the next morning. The ronin, by contrast, doesn’t even set out for the island until he can be sure he’ll reach the site by high tide the next morning.

When Musashi is about to begin his journey to the island, he’s met at the shore by Otsu, accompanied by Akemi, Matahachi and even Obaba, who no longer hates him.5 Otsu tries to persuade the ronin to back out of the duel, but he replies that the path of the sword is “ruthless.” She angrily replies that it is really his heart, not his sword, which is ruthless, and adds that even if he survives, he will only have more blood on his hands. She refuses to send him off with a smile, like a good warrior’s wife. He boards the boat to begin the journey.

On the way to Funajima, he sees boats on nearby islands which his boatman, Sasuke, tells him ought to be deserted. The ronin realizes that Sasaki’s allies must have brought men to kill him if he wins. With a knife, the ronin begins to cut an abandoned oar he had found on the shore before setting forth, turning it into a club.

Sasaki’s party on the island is exasperated because Musashi is so late. Sasaki informs them that this is the ronin’s usual strategy and that they shouldn’t be concerned about it, but he is clearly anxious. They suddenly spot the ronin’s boat approaching. Musashi tells the boatman to hold onto his sword, because he will try to kill Sasaki with the oar.

When the boat reaches shore and Musashi disembarks, standing ankle-deep in the water, Kojirō runs down to the water’s edge to call him a coward for being late. Musashi is silent. Sasaki unsheathes his sword and tosses away the sheath. The ronin tells his adversary that he has already lost: if he had confidence in winning, he wouldn’t have thrown away his sheath. Sasaki dismisses this as nonsense, but is clearly unnerved.

Musashi, his feet still in the water, begins to run faster and faster along the shore, while Sasaki runs parallel to him. When he gets far enough ahead of his adversary, the ronin turns to face Sasaki, and then leaps over him. Musashi’s headband loosens and drops, indicating that his rival had managed to cut it with his sword. However, blood begins to flow down Sasaki’s forehead from where the ronin had hit him with the oar, and he collapses in the sand.

Musashi examines Sasaki’s motionless body to make sure his adversary is dead, then makes a beeline for the boat to escape. When he gets in and the boatman begins to cast off, Sasaki’s allies run down to the sea to kill him. A group of archers prepares to take aim at the ronin, but Nagaoka orders them to stop.

As Sasuke rows them away from shore, Musashi regrets that he will never again meet an opponent of Sasaki’s extraordinary skill. He looks down at the hand that held the oar and sees that there is blood on it, as Otsu had predicted. He recalls his past battles, without pleasure.

He realizes that ten years had passed since he had emerged from Shirasagi castle to dedicate himself to the path of the sword, yet he feels hollow. “So the sword is nothing but a weapon after all,” he says. In disgust, he throws the oar with which he had killed his enemy overboard. He leans back in the boat as the boatman rows him away to safety.

(Continued on Page 6)

[…] The Miyamoto Musashi Series (Miyamoto Musashi, Parts I-V, 宮本武蔵), 1961-1965 January 9,… […]