Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

(Continued from Page 5)

In the commentary to Part I of this series, I had raised the question: did Uchida employ the character of Musashi as a kind of alter ego, to represent his own complex and baffling personality?

I’ve already asserted in my review of A Bloody Spear at Mt. Fuji on this site that the three male stars who dominate Uchida’s postwar cinema came to symbolize different cultural and psychological realities for the filmmaker. The middle-aged star Kataoka Chiezō, even when portraying a humble spear carrier or a foolish merchant in love, stood for Japan’s venerable (and vulnerable) patriarchal traditions, to which Uchida was still very strongly drawn, despite his leftist inclinations. Mikuni Rentarō, on the other hand, symbolized the unpredictable, Americanized, violent modern world. (His performance as the benign though somewhat ambiguous Takuan in the pentalogy is a rare exception to this rule.) But Nakamura Kinnosuke, I believe, served as a stand-in for Uchida himself and his restless, questing, insatiable soul – and never more so than in this series.

As it was for Musashi, ambition for Uchida was a constant from his youth. Ambition is what drew him to mentors like the famous novelist Tanazaki Jun’ichirō and seasoned filmmakers like Thomas Kurihara and Kinugasa Teinosuke in the 1920s. And after he had established his reputation as a director, ambition is what kept him striving for total independence, so as to be able to make the movies he wanted to make, in the way he wanted to make them. The film industry being what it was, he never fully attained this cherished goal, even in the postwar era, when he was the master director of Toei Studios.

Finally, ambition led him irresistibly to seek the role of eyewitness to history when he decided to remain in revolution-torn China after the end of the war, perhaps with the ultimate aim of making a movie drawn from his experiences there. This decision nearly derailed his career upon his belated return to fiercely anti-Communist postwar Japan, where only the direct intervention of powerful friends such as Shimizu Hiroshi, Ozu and Mizoguchi saved him.

Thus, Uchida may well have found in Miyamoto Musashi a mirror image of himself, or rather, his worst self. Despite the cinematic Musashi’s seemingly indomitable will, his most important emotional attributes are not his courage and self-possession in battle, but frustration, disillusionment and, above all, guilt. Uchida’s experiences in China, according to the film editor Kishi Fumiko, who shared these with him, involved a double burden of shame: guilt towards his fellow Japanese, whom he felt that he had failed as their leader, and guilt towards his own family back in Japan, whom he had willfully abandoned, particularly his wife. In fact, according to Kishi herself, his marriage apparently never recovered from his long sojourn in China.1

Uchida, if he wished to understand a character like Musashi who was willing to sacrifice everything, even the happiness of his loved ones, to a glorious ideal, had only to look in the mirror. Thus, at the end of the series, despite the fact that Miyamoto defeats the second-best swordsman in Japan and gets away alive, he feels no satisfaction, never mind elation, but only a sense of emptiness.

It’s very interesting that the version of Musashi played by Mifune Toshiro, at the end of Inagaki Hiroshi’s 1950s trilogy, cries over the death of Sasaki, mourning the beauty of his adversary as a personal loss. Nakamura’s Musashi, on the other hand, only regrets Sasaki’s death because he knows he’ll never again, for the rest of his life, find an opponent so magnificent. He’s rather like Alexander the Great, grieving that he has no more worlds to conquer.

Thus, we might identify a major, and very personal, theme of this series as the futility of victory, which consistently undercuts what the young or naïve viewer might perceive – and enjoy – as the glorification of the exploits of Japan’s greatest swordsman. The twin (related) themes of guilt and the emptiness of “success” link this series to A Fugitive from the Past – and to the creator of both works.

Like other installments in the five-part series – and apparently like the novel upon which it is based – the narrative often tends towards incoherence by going off on unrelated tangents without warning, as if momentarily forgetting that this is ultimately the story of a mortal conflict between two men. The worst example of this in Part V occurs early in the movie, when Musashi by chance meets the little boy Iori and suddenly decides, for no apparent reason, to settle down and help the child, a total stranger, farm his nearly barren piece of land.

Despite such lapses, however, this installment of the series works better than the other four, even Part I, due to the relentlessness with which the narrative, after the setting has changed to Edo about a half an hour into the film, moves towards the inevitable clash between the two master swordsmen.2 From this point on, scenes and shots within scenes are subtly but perceptibly shorter, establishing a faster rhythm without the viewer being fully aware of it.

Most importantly, Part V focuses on Sasaki’s swordsmanship, rather than Musashi’s. It seems to me entirely possible that Uchida did not believe Takakura Ken’s skill with the sword was quite up to the level of Nakamura’s. In any case, throughout the series, we never really see Sasaki wield the sword to the degree that Musashi does, yet Uchida always manages, through visual sleight of hand, to compel the audience’s belief in Sasaki’s extraordinary talents.

A fine example of this is the brilliant scene of Sasaki’s duel with the spearman Okaya of the Hosokawa Clan. Before the fight, the spearman is in the process of covering up the point of his weapon with a cloth, which, we may assume, was standard procedure for demonstration matches to prevent anybody getting hurt. Sasaki makes the unusual request that Okaya keep his spear uncovered, which, of course, would make of it a potentially lethal weapon.

Okaya in turn, as a point of honor, demands that Sasaki fight with a real sword with a sharpened blade, rather than a bokken (wooden practice sword). But Sasaki cleverly claims that he, as a ronin who has not (yet) been accepted as a full member of the clan, doesn’t have the right to use a sharpened sword against a clan member in front of the daimyō, and insists on fighting with his bokken. Out of curiosity, perhaps, Lord Hosokawa grants his strange request.

The fight begins with the focus on Okaya, with Sasaki’s back to the camera. Then the camera settles on a closeup of Okaya’s feet, which tell the whole story of how Sasaki, despite his multiple disadvantages, is dominating this match, as Okaya is forced to retreat from and sidestep his opponent again and again.

The camera slowly rises, with the focus again on Okaya. His face reveals his anxiety and confusion as he struggles to cope with the superior speed and agility of his adversary.

Finally, there’s an extreme closeup of Sasaki delivering a single, decisive blow. Suddenly Okaya is kneeling on the ground with Sasaki hovering over him, and Nagaoka calls the match.

In this part of the film, it is Sasaki’s psychological weaknesses rather than his swordfighting strengths that Uchida wishes to stress. The hubris that makes him challenge Musashi to a duel despite having no quarrel with the ronin is counterbalanced by his tendency to lose his cool in the face of Musashi’s crafty but ethically dubious ploys. The odd thing is that Sasaki, unlike the stupid Denshichirō in Part IV, understands perfectly that Miyamoto is psyching him out, but it doesn’t matter: he’s still demoralized.

The perfect example of this is when the Hosokawa Clan and their supporters wait on the island of Funajima for Musashi, who’s over an hour late. The others are outraged that the ronin is keeping them waiting, but Sasaki points out that Musashi always deliberately shows up to his duels late, and he suggests that they all should calm down. Yet he himself at that moment looks exactly like Okaya in the earlier duel, struggling to keep up with an adversary against whom he is (psychologically) overmatched.

In a sense, Sasaki is like a character in a Shakespeare play – Henry V, for example – who knows, or at least senses, that he’s fated to lose, but cannot swerve from his tragic destiny. The difference is that Shakespeare references the Christian God in his attempt to elucidate the workings of fate, whereas Uchida relies on the simple mechanics of karma to explain why whatever happens in the narrative happens – that and the powerful force of Musashi’s more pragmatic and amoral personality.

But Sasaki, in another sense, ultimately had his revenge, because the actor who plays him in this movie would soon become a much bigger star than the one who plays Musashi, Nakamura Kinnosuke. By the time this final installment of the five-part series came out, Takakura Ken, after a decade of struggling, had finally become – after the release, earlier in the year, of the smash hit crime thriller Abashiri Prison (Abashiri bangaichi, Ishii Teruo, 1965) – a superstar in Japan. And a superstar he would remain until his death 49 years later, ultimately inspiring a huge fan base not just in Japan, but in mainland China and the rest of Asia, and even becoming a cult favorite in the U.S.3

We will conclude our analysis of the Musashi pentalogy with a summary of the pros and cons of the series as a whole, and an evaluation (“score”) for each installment in the series.

Otsu: Paghat the Ratgirl, in this blog post, makes the case that Musashi’s women come off worse in Inagaki’s version of Yoshikawa’s novel than in any of the other versions, including Uchida’s. I don’t really agree. Yachigusa Kaoru, who plays Otsu in Inagaki’s trilogy, displays, in my opinion, a combination of shyness and spunk in the role that’s rather appealing. But Irie Wakaba (who was making her debut in Part I) seems to me overly sweet, and nearly all the scenes involving her and Musashi, except for the one in which she sets him free from his cedar tree prison in Part I, are painfully sentimental. Her character does, admittedly, prove that she possesses a spine near the end of Part V, when she refuses to support his duel with Sasaki. But for me, that minor rebellion is a case of too little, too late, and the blame for this must lie with Uchida.

Obaba: The character of the old village woman who seeks vengeance against Musashi for dragging her weak son, Matahachi, into the war, starts out annoying and goes downhill from there. Obaba is clearly intended as comic relief, true, but her grating presence is a bit too overbearing to be truly funny, and I longed for the character to disappear from the narrative long before she did. It is amusing when somebody finally asks her which family member Musashi had killed to set her off on her quest for revenge, and she has to admit that the ronin didn’t kill any of them. But it’s simply unbelievable that not one of her supporters up to that point had thought to ask her that simple question, which would have put a swift end to her absurd vendetta.

Even in the scene that’s supposed to be her most poignant, when she realizes that her son has given her a grandchild (with Akemi) and tears appear in her eyes, the actress chews the scenery so shamelessly that we feel nothing for the character. Naniwa Chieko’s performance in the role is particularly disappointing, because she was admirably restrained in (for example) her small but memorable role as the serving maid in Sanshō the Bailiff (Sanshō Dayū, Mizoguchi Kenji, 1954), and she was wonderfully creepy, but not over-the-top, as a brothel employee in Uchida’s Chikamatsu’s Love in Osaka. But the blame for allowing the actress to get out of control lies, again, squarely with Uchida himself.

Broken promises, illogical plot twists and absurd coincidences: It would be a vain endeavor to try to list all the plot holes in this enormously long work, most of which (I assume) were inherited, so to speak, from Yoshikawa Eiji’s epic novel. I’ve already mentioned the extremely odd fact that in Part I Takuan, to capture Musashi a second time, promises to lead him to his kidnapped sister, Okin. It turns out that the priest apparently hasn’t the faintest idea where the sister is, and the Okin subplot is then promptly dropped from the narrative, as if she had never existed. Just as strangely, Musashi in Part IV, when he separates from the boy Jotarō, promises to meet up with him again if he survives his encounter with the Yoshioka students, yet Jotarō is never afterwards seen or alluded to.

I’ve already mentioned in the commentary to this installment the irrelevant scenes in which Musashi suddenly decides to become a farmer again. There’s also the curious fact that, after Sasaki is killed, his allies don’t immediately rush to attack Musashi as expected, but wait until he has boarded the boat and is ready to be rowed to safety to pursue him. Finally, there are the many scenes in which Sasaki, in a heavy-handed attempt at foreshadowing, “coincidentally” pops up again and again in the narrative, as when he intervenes in Miyamoto’s dispute with the Yoshioka students during the showdown in the town in Part IV. As a credited co-writer of the script, Uchida is responsible for all these lapses, even if at least some of them may also exist in the source novel.

Moral ambiguity: As is only appropriate for a character in a film by the director of A Fugitive from the Past (which was released earlier in the same year as the final installment of this series), the soul of the “hero” is a patchwork quilt of good and evil, light and dark. When Musashi, at the end of Part IV, attempts to justify to himself the killing of the child Genjirō, we can choose to view his speech as an attempt by the filmmakers to gloss over his guilt, but we can also interpret the monologue as his struggle to come to terms with the mystery of his capacity for violence.

It’s perfectly true that Miyamoto is capable of killing a little boy in the heat of battle. But he’s also capable of adopting children and caring for them (e.g., Jotarō, Iori). He can ruthlessly pursue victory against his enemies at any cost. But he can also be a generous friend (e.g., to Koetsu), and even cultivate his aesthetic side in moments of tranquility. (And in fact, the historical Musashi was actually a very gifted painter).4

Paghat in her blog describes these contradictions admirably, with her eccentrically-punctuated prose: “[Directors] Tai Kato & Yasuo Kohata [actually, Yasuo Furuhata] preferred the grimier, grosser Musashi rendering him very much the nihilistic anti-hero if not an outright villain. But Uchida had so much room [in his multipart narrative] that he could let [Nakamura] Kinnosuke create a character who conveys sparks of nobility even at his grossest, & as he develops into a more intelligent & spiritual man, he remains a trickster who takes advantage of opponents, using others’ greater sense of honor to win every duel even if he has to cheat. This is a much more compelling portrait than either the complete whitewash of Inagaki or the complete soiling of Tai Kato. Kinnosuke plays the character with greaer [sic] ambiguity.” An awareness of the moral ambiguity of human actions is at the very core of Uchida’s art. So now I understand, as I really didn’t when I began to compose this review, why he chose to film Musashi’s epic story, and to do so in such as expansive way.

Fight scenes: During the series’ initial run, it was surely the swordfight scenes that brought many in the audience, particularly young males, into the theaters, and so, in a sense, the film stands or falls on the effectiveness of such scenes. I believe the fight scenes in the series to be uneven in quality, but the best of these – particularly the duel with Okaya in Part V – are among the most imaginative the director ever filmed.

The sudden ending of the final duel can be dismissed, and often has been, as anticlimactic, or it can be seen as startlingly and dramatically unexpected, depending on one’s point-of-view. (In some ways, I prefer the final duel in Inagaki’s version, which more effectively contrasted the different swordfighting styles of Sasaki and Musashi, as well as demonstrated visually the negative effect of the rising sun, which was in Sasaki’s eyes (as Musashi had planned), on the swordsman’s performance.) And though I never found credible the big seventy-three-against-one duel at the climax of Part IV, and still don’t, I can now appreciate, having studied it, how difficult it was to film, and the immense planning and effort and skill that went into the staging of that sequence.5 And the shocking shot of the killing of the little boy remains haunting – as it was intended to be.

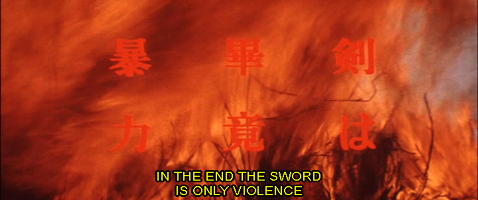

Pacifist stance: The series ends with an implied affirmation of pacifism on the part of the filmmaker, even though the historical Musashi, after defeating Sasaki, went on to kill many more people, including on the battlefield. Ironically, Miyamoto in the film comes to agree with Sasaki’s view that the sword does not have a heart or soul, that it’s “nothing but a weapon after all.” With disgust, he throws the oar/club with which he killed Kojirō – his impromptu “sword” – into the sea.

Uchida, through his protagonist, seems to assert the futility of violence, not just because it has failed to make him safe, but because “winning” no longer gives the swordsman any gratification. In Uchida’s final film, Swords of Death, this stance is made even more explicit, with the inclusion of a title card at the end reading “The sword is simply large-scale destruction” (as Gregory Barrett translates the text): an unprecedented editorial intrusion by the filmmaker into one of his narratives.6

My final “score” (IMDb rating) for each of the five films is as follows:

The epic book and movie Miyamoto Musashi have sometimes been compared with, respectively, Margaret Mitchell’s novel Gone With the Wind and the movie (directed by Victor Fleming) made from it. Like that Hollywood classic, Uchida’s gigantic work only intermittently attains the heights of cinematic artistry, but also like the 1939 film, it partly compensates for this through sheer entertainment value.

J-Film Pow-Wow (Matthew Hardstaff): Very favorable review of the first installment

Asia Shock Blog (Patrick Galloway): Again, mostly a review of Part I

Gotterdammerung.org (Branislav L. Slantchev): This reviewer prefers the Inagaki version of the saga to Uchida’s

Weird Wild Realm (Paghat the Ratgirl): A typically informative and insightful analysis by this blogger, in which she states her preference for Uchida’s pentalogy over Inagaki’s trilogy, but nevertheless points out perceived flaws in Uchida’s epic work

Barrett, Gregory, Archetypes in Japanese Film: The Sociopolitical and Religious Significance of the Principal Heroes and Heroines (1989), pp. 51-56. Susquehanna University Press: Associated University Presses, Cranbury; London; Mississauga: Barrett’s analysis of the character of Musashi as depicted by various directors over the years includes a strongly-worded critique of Uchida’s five-part Toei series, as well as of his final film (for Toho), Swords of Death (aka, Miyamoto Musashi VI).

[…] The Miyamoto Musashi Series (Miyamoto Musashi, Parts I-V, 宮本武蔵), 1961-1965 January 9,… […]