Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

(Continued from page 1)

The Outsiders is definitely the most “Hollywood” of the twenty-five films by Uchida Tomu that I’ve seen so far, which is probably the biggest reason for my ambivalent feelings about it. Even Police Officer from 1933, which drew very heavily from U.S. crime films of the time, was not quite as “American” as this picture is, both in its traditional narrative structure and its very familiar (to the Western viewer) imagery.

This influence is obvious from the very first shot, which could easily be mistaken for the opening of a 1950s Western – specifically, the type of Western directed by Anthony Mann, involving plenty of location shooting in rugged terrain, usually in vibrant color. Against a vast landscape, a lone male rider approaches from the distance on horseback. This image, rendered memorable by Uchida’s excellent cinematographer Nishikawa Shōei, epitomizes the timeless Romantic appeal of the Western genre: the sense of limitless freedom and possibility of the untamed frontier.1

But Uchida hasn’t set aside his penchant for irony here, for what we are seeing is not Montana in post-Civil War America, but Hokkaidō, Japan’s northernmost island, in the present: that is, 1958, the year of the movie’s release. Furthermore, the rider, Kazamori Ichitarō, is not a cowboy or lawman, but a rebellious member of Japan’s persecuted, indigenous Ainu minority, and his adversary is not some lone gunman or cattle rustler, but the unjust social order itself.

Rather than a personification of freedom, therefore, Byakki (“Phoenix”), as the hero is called, is actually a victim struggling to attain freedom for himself and his people. (He’s a very modern character in his single-minded determination to achieve this goal by any means necessary.) It is fitting that Byakki is much smaller in the frame above than the James Stewart character in Mann’s film because, in a sense, the scenic beauty of the area mocks the character, offering a fantasy of liberty that Byakki knows is denied him in the real world because of his race.

The reason Byakki is riding through the countryside is to distribute gifts among Ainu villagers scattered all over the area, particularly the native children; he seems a cross between Santa Claus and Robin Hood. We are never told how he managed to obtain these goods, which include books and even a puppy. And though I don’t quite believe he literally stole these items from rich whites, the possibility is not unthinkable, for he’s driven not only by a stern sense of responsibility to his people, but by rage against the Shamos – the Japanese. He’s particularly infuriated by their penchant for interbreeding with his people, which, he fears, might eventually eliminate the Ainu completely as a distinct people.

One of the things I like about the English title of the film – which is so much more evocative than its odd, rather opaque Japanese title (derived from the original novel), which translates as “Festival of Lakes and Forests” – is that it remains ambiguous just who the “outsiders” actually are. In an obvious sense, the Ainu are “outside” the mainstream of Japanese society: all the Ainu characters, to a man and woman, constantly struggle against discrimination and the ways in which it threatens to warp their perceptions of themselves.

Yet in another sense, Yukiko, the ethnic Japanese painter from Tokyo, is the true outsider in this narrative, for she’s the only character we encounter for whom this environment is utterly foreign. So we, the audience, also become outsiders, for it is through Yukiko’s eyes that we perceive almost everything in this beautiful, but harsh and alien world.

Including this character has two obvious advantages. The device makes it possible for exposition to be plausibly introduced into the narrative, since Yukiko, as a Shamo from the big city, would not immediately know what’s going on or what the relationships between the characters mean, and so must be informed of all this by the other characters. Centering Yukiko in the narrative also allows for greater detachment from – and thus a more objective view of – the events depicted, which would not be the case if all narrative events were conveyed through, for example, Byakki’s point-of-view.

A third advantage is that it partly forestalls one possible line of attack on the film from critics and the Ainu themselves: namely, that Uchida, a Japanese, is pretending to speak for an entire oppressed people. But this brings up the whole thorny issue of authenticity, which we will address in more detail in a later section below.

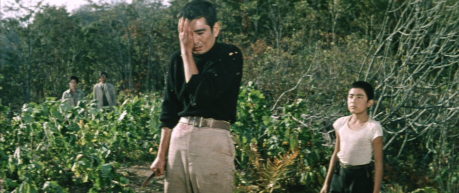

In his performance as Byakki, Takakura is quite obviously channeling the rebel figure of Marlon Brando… torn shirt and all.2 This wasn’t the first time Uchida had featured an “alpha male” in a central role. Three years earlier, in Uchida’s A Hole of My Own Making (Jibun no ana no nakade, 1955), Mikuni Rentarō – who in this film plays the complex antagonist, Oiwa Takeshi – portrayed a brazenly sexual character, presented as the villain of the piece.

But in this film the equally aggressive hero, Byakki, is fascinatingly ambiguous: idealistic, even heroic, but possibly also dangerous in his fanatical devotion to his righteous cause and certainly not reverent towards women, Shamo or otherwise. Given these traits, and also Byakki’s sheer physicality, Brando was the perfect model for the character. That said, this (ironically) very Japanese character type transcends the Hollywood template; indeed, Takakura’s acting here is not far removed from his tough-guy performances in yakuza roles.

A case in point is the scene that takes place in Tsuruko’s bar, after everyone but Byakki, Yukiko and Tsuruko herself have gone. In a significant shot, taken from behind the bar facing outwards, Byakki is shown with his back to the audience in the center of the composition, an imposing figure, while the two women, on bar stools in the middle distance, appear on either side of him facing the camera. The implication of Byakki’s patriarchal power and authority is obvious, though only one of the two women, Yukiko, is interested in him sexually. I doubt that an American movie of the time would have displayed its male character’s dominant role quite so blatantly.

However, Uchida’s protagonist also demonstrates another, contradictory Brando-like trait: vulnerability. With the possible exception of the brutal Stanley in A Streetcar Named Desire, all the Hollywood actor’s classic 1950s performances – whether playing a Mexican revolutionary, a motorcycle gang leader, an ancient Roman or a waterfront layabout – manage to bring out the soft, humane side in his rough-hewn characters. It’s the confounding combination of savage violence (or the threat thereof) and gentleness, of animality and a kind of innocence, that makes Brando’s early work so fascinating to watch even now.

Takakura’s Byakki is more stolid and unyielding than most of Brando’s characters, but glimpses of a softer or at least less confident side can sometimes be seen. Such a moment occurs when he reacts with confusion and hurt at the taunting he receives from the “kidnapped” Yukiko, and particularly after his final confrontation with Oiwa, when she and Dr. Ike approach him and he turns his head away to avoid showing them his wounded face.

Byakki’s vulnerability is also displayed when he is forced, in these final moments, to confront the consequences of his misguided zeal. He comes across a dead body in the water that turns out to be Sugita – an apparent suicide, following Byakki’s violent rejection of his attempted reconciliation with Mitsu. But Byakki, seemingly influenced by his sister’s spirit of compassion and forgiveness, takes responsibility for his actions in a remarkable way: he lifts the corpse out of the lake and places it face-up near the bow of the boat, like a totem, and paddles off into the unknown.

In the end, Byakki – who, in a final majestic shot, disappears in his canoe into the sunset – is transformed into a mythic figure, like Brando in Elia Kazan’s Viva Zapata! (1952). Though the untamed hero can never be assimilated into the social order, neither can he ever be completely destroyed (symbolized by his child in Yukiko’s womb).3

Despite the strong male figures played by Takakura and Mikuni, perhaps the movie’s most interesting characters, ultimately, are the women, both Shamo and Ainu. Indeed, the latter experience both racial and gender discrimination, and it’s fascinating to observe the ways in which they deal with this double burden.

The neurotic, unhappy Shigeko vacillates between protecting and destroying Yukiko’s (bad) painting. She ultimately flees her own image, resisting representation even by a well-meaning, “liberal” Japanese.

The bar manager, Tsuruko, seems the most resigned of the three main female Ainu characters. She takes the taunting of the local men in stride: she’s obviously used to such treatment. When she recalls to Yukiko how her former husband, Dr. Ike, reduced her to an ethnological “object” during their marriage, there’s no bitterness in her voice, only wistful regret.4 And though she may not share Byakki’s militancy, she doesn’t appear to disapprove of it either. She hopes that her lot as an Ainu may somehow improve, but she’s determined to survive whether it does or not.

Mitsu is perhaps the most complex female character, as it is she who suffers the most from oppression. In her first flashback sequence, we see her, as a girl, running away with her brother from a Shamo policeman, having caught a huge fish, apparently illegally. She finds shelter with Sugita, a sympathetic Shamo teacher who protects them from the law. The relationship between the girl and the much older man gradually deepens and they fall in love. But Sugita betrays her by getting drunk and calling off their engagement, because he can’t deal with the social ostracism that would necessarily follow marriage to an Ainu. In a fit of anger, she urges her younger brother to kill Sugita, but is relieved when the boy can’t bring himself to murder the man.

Despite her negative experience with the Japanese, Mitsu approaches Yukiko without hostility to relate her story. Later, in her hospital room, in a spirit of forgiveness she receives the alcoholic Sugita, who brings two apples as a gift. It seems likely that the two lonely people will rekindle their romance – until Byakki (her brother) shows up and throws Sugita out of the room because of his opposition to the man… and to intermarriage between the Ainu and Shamos. Of all the Ainu characters, Mitsu is the most positive – or idealized, depending on one’s point-of-view – because she doesn’t internalize her anger, but rather respects the humanity of everyone she encounters.

There’s a childlike aspect to Yukiko, the only Shamo female character, that’s not shared by the Ainu women. The keynote of her personality is an unassuming curiosity: she truly wants to understand the people and things she’s seeing. In a sense, she serves as Uchida’s surrogate, with the painter’s canvas rather than the movie camera the medium by which she conveys what she’s witnessed, and also like Uchida, she can’t remain morally neutral. Yes, Yukiko has strong feelings, including erotic feelings, for Byakki. But even if she didn’t, she would probably still put herself in danger to try and stop the enraged Oiwa from shooting him, out of simple compassion.

As Yukiko, the great Kagawa Kyōko, an actress legendary for her poise, confidence and “realness,” seems very uncharacteristically tentative and distant. I believe this is almost the only performance of hers I’ve ever seen in which I was seldom certain what her character was thinking. On the other hand, this tentative and vulnerable quality is appropriate to Yukiko and her ambiguous situation. And there’s a quiet but real eroticism that’s very unusual in Kagawa’s work, and a welcome change of pace for her.

(Continued on page 3)