Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

(Continued from Page 1)

Nakamura Kinnosuke (aka, Yorozuya Kinnosuke) was born into a family of Kabuki performers. He entered the film industry in 1954 in his early twenties while simultaneously continuing his theatrical career, and he eventually became one of the great male jidai-geki stars of his generation, along with Ōkawa Hashizō (see our review of The Mad Fox (Koiya koi nasuna koi, 1962)), Ichikawa Raizō and Katsu Shintarō. For Uchida, Nakamura went on to portray the lead role in Chikamatsu’s Love in Osaka (Naniwa no koi no monogatari, 1959), the title character in the five-part Miyamoto Musashi series (1961-1965), and Musashi again in the director’s final, posthumously-released film, Swords of Death (Shinken Shōbu, 1971). He also worked for other distinguished directors, such as Uchida’s friend Itō Daisuke (Conspirator (Hangyaku-ji, 1961)), Imai Tadashi (Cruel Tales of Bushido (Bushidō zankoku monogatari, 1963)), Inagaki Hiroshi (Samurai Banners (Fūrin Kazan, 1969)), Toyoda Shirō (Portrait of Hell (Jigokuhen, 1969)), Gosho Hideo (Goyōkin, 1969), Fukusaku Kinji (The Fall of Ako Castle, (Akō-jō danzetsu, 1970)), and many others. He was married to two movie stars: Arima Ineko (his Chikamatsu’s Love in Osaka co-star) and Awaji Keiko; both marriages ended in divorce. Perhaps the most famous role of his career was not in films, but on television: that of Ogami Ittō in the Lone Wolf and Cub series from 1973 to 1976. (This is not to be confused with the movie series of the same name, starring Wakayama Tomisaburo as Ittō.) Nakamura died in March, 1997, age 64.

Kogure Michiyo was one of Japanese Cinema’s most acclaimed and respected actresses in the immediate postwar era. She was a most unusual performer in that, at the height of her career, she alternated between leading roles and relatively minor character parts (as in this film), excelling at both. For Kurosawa, she played the mistress of Mifune Toshiro’s character in Drunken Angel (Yoidore Tenshi, 1948); for Ozu, she portrayed, in perhaps her most famous role, a frustrated housewife in The Flavor of Green Tea Over Rice (Ochazuke no aji, 1952); and for Mizoguchi, she appeared in A Portrait of Madame Yuki (Yuki fuzin ezu, 1950), Gion Festival Music (aka, A Geisha: Gion bayashi, 1953), Tales of the Taira Clan (aka Taira Clan Saga: Shin Heike Monogatari,1955) and in the small but memorable role of a pragmatic prostitute in the director’s final film, Street of Shame (Akasen Chitai, 1956). For Uchida, Kogure later played, with great gusto, the tough, no-nonsense outlaw Okō in the Miyamoto Musashi series (1961-1965). One of her very last roles was as the mother of the heroine in the 23rd installment of Shochiku’s long-running Tora-san series: Tora-san the Matchmaker (Otoko wa tsurai yo: Tonderu Torajirō, 1979). Of this performance, Stuart Galbraith IV wrote that “her role isn’t especially memorable, but she nails her character… wonderfully well,” and he added that Kogure was one of Japanese cinema’s “all-time great actresses.” She died in 1990.

Oka Satomi specialized in playing sweet young heroines for Toei, and was called that studio’s “princess.” While still a high-school student, she had won a beauty contest sponsored by RKO Studios and was crowned “Miss Cinderella.” She was then offered by RKO a trip to America in the spring of 1953 to tour Hollywood, and met many movie stars there. Oka was working as a secretary for RKO when she signed an acting contract with Toei, and she quickly became a popular star. For Uchida, she had previously made The Horse Boy (1957), and later appeared as Akemi in the Miyamoto Musashi series (1961-1965). However, according to Stuart Galbraith IV in his commentary to the DVD edition of that series, her experience with Uchida on that production was so tense that she seriously considered quitting acting. She retired in the early 1990s.

Yamagata Isao was born in London in 1915. During the Second World War, he founded a theatrical company in Japan with future star Sō Yamamura, and didn’t begin working in the film industry until the end of the 1940s. Despite this somewhat late start, he became an extremely prolific character actor, playing mostly villainous roles. For Uchida, Yamagata portrayed Ishida, the evil advisor of Toyotomi Hideyoshi (played by Tōno Eijirō), in The Master Spearman. He also appeared in Uchida’s The Thief Is Shogun’s Kin and the fourth installment (1964) of the five-part Musashi series. He remained active in films up to the mid-to-late 1980s, and died in 1996 at the age of 80.

Trivia note: Several of the actors who appear in Uchida’s trilogy had also acted in previous adaptations of Nakazano’s novel. Ōkōchi Denjirō, who portrays, in the trilogy, Hyōma’s dōjō master, Shimada Toranosuke, had played the leading role, Ryūnosuke, in the first version of the story – titled in Japanese, like all other versions, Daibosatsu tōge – directed by Inagaki Hiroshi in 1935 and 1936, while veteran actor Tsukigata Ryūnosuke (the kindly thief Shichibei in Uchida’s work) had also appeared in Inagaki’s two-part epic in the role of Shimada. Kaga Kunio, who appears as the itinerant entertainer Tomo in the trilogy, had portrayed Bun’nojo, the brother of Hyōma, in Toei’s earlier (1953) trilogy, directed by Watanabe Kunio. Kataoka Eijirō, who plays the role of Kinzō in this work, as well as appearing in important supporting roles in Uchida’s A Bloody Spear at Mt. Fuji and Hero of the Red-Light District, had also played Hyōma under his other stage name, Shimada Teruo, in the 1953 version. And Kishii Akira portrayed the loyal servant Yohachi in both Watanabe’s and Uchida’s trilogies.

“The eyes are the window to one’s heart. Now that they’ve been closed, my heart is in darkness. It could have been in darkness to begin with.” – Tsukue Ryūnosuke (Dialogue from Part II of the trilogy)

There exist in some countries very flawed writers who are paradoxically important, in that each possesses a highly original and memorable sensibility that manages to connect with their national culture in some fundamental and profound way. The Marquis de Sade – whose work is full of horrendous clichés, not to mention outrageous and often disgusting tastelessness – is one of these, because, despite his artistic sins, he managed to create a compelling and disturbing vision of the world and of human life that was relevant to his times, and even to eras long after his own.

I’ve never read the work of Nakazato Kaizan (birth name Nakazato Yanosuke) – as far as I know, his work has never been translated into English – a novelist who worked on his colossal 41-volume magnum opus, Daibosatsu tōge (The Great Bodhisattva Pass), for over thirty years, though it remained unfinished at his death in 1944. But at least four other movies besides this one have been made of his most famous work.1 Because of these other adaptations, I can say with confidence that as a constructor of narratives, Nakazato leaves much to be desired. His plotting is full of poorly-motivated characters, chief among them the “good thief” Shichibei,2 wildly implausible incidents – both the protagonist and his young adversary, Hyōma, dispatch whole mobs of adversaries single-handed, in Ryūnosuke’s case, even when blind – and totally coincidental meetings and reunions whose unlikelihood would make Dickens blush.

Furthermore, although Uchida Tomu had had extensive experience directing multipart films in the prewar era,3 his control of the narrative here is often spotty. There are sequences that seem to me completely pointless distractions – such as the entertainer Okimi and Lord Komai’s platonic relationship in the third part of the trilogy, or her colleague Tomo’s rather comical confrontation with Ryūnosuke in the same film4 – and there are other parts of the trilogy in which scenes appear to have been omitted that might have clarified the plot and/or the characters. For example, in Part II, there’s not much transition from Ryūnosuke’s mental breakdown at the geisha house to his recovery in Miwa Village, nor any explanation as to how Otoyo, who at this point barely knows the samurai, managed to find him there and nurse him back to health.

By far the most interesting and successful element in this movie is the memorable protagonist that Nakazato created: the sociopathic, deadly, utterly affectless samurai Tsukue Ryūnosuke – perhaps the most “anti” antihero in all literature. Ryūnosuke, however, is not a freak; his pathology merely mirrors, in an extreme manner, the historical pathology of his class. He’s just one step beyond the ordinary madness and cruelty of his extremely stratified and essentially lawless world. To elaborate upon our comparison with the Marquis de Sade, Nakazato in his book, which is set in the twilight years of the shogunate, was depicting, like Sade, a decadent aristocratic caste near the end of its long rule, after it had already enjoyed centuries of legal and social impunity for its many crimes and abuses.

Nakazato includes in his saga another villainous character: Lord Kamio (spelled “Kamiya” in some versions of the saga), played in the trilogy by Yamagata Isao. Kamio displays all the familiar vices of such aristocrats: corruption, arrogance, cowardice and unbridled lust. As such, he’s a reassuringly familiar and even banal bad guy. But Ryūnosuke is different. His evil is, in a way, pure: he’s not motivated by a desire for personal gain, or even power for its own sake, but by an irresistible urge to carry out brutal, pointless killings.

The first of these takes the life of the grandfather of the heroine, Omatsu, at the Great Buddha Pass alluded to in the film’s Japanese title: a sin that mixes gratuitous violence with blasphemy, since the pass is a sacred site. Visually, this opening scene is stunning, in the contrast between the quiet beauty and majesty of the hills as Uchida photographs them and the disturbing emotions created in the viewer by Ryūnosuke’s utterly motiveless crime. And from this point on, it’s as if the samurai’s sword were a wicked, living thing with a mind of its own, drawing him helplessly towards ever more outrageous killings.5

Ironically, his sickness makes him a very bad “hit man.” Although the Shinsengumi and later Lord Kamio attempt to use both his skills and his lack of conscience for their own political or personal ends, he’s totally unwilling to kill when not in the mood. Even when Ryūnosuke tries to carry out an “assignment” – his attempted assassination of the good Lord Komai – he couches it in personal terms, telling his victim that he is merely testing his new sword.6 (It’s not clear whether he really means this or is merely protecting the identity of his employer, Kamio; I suspect the former is true.)

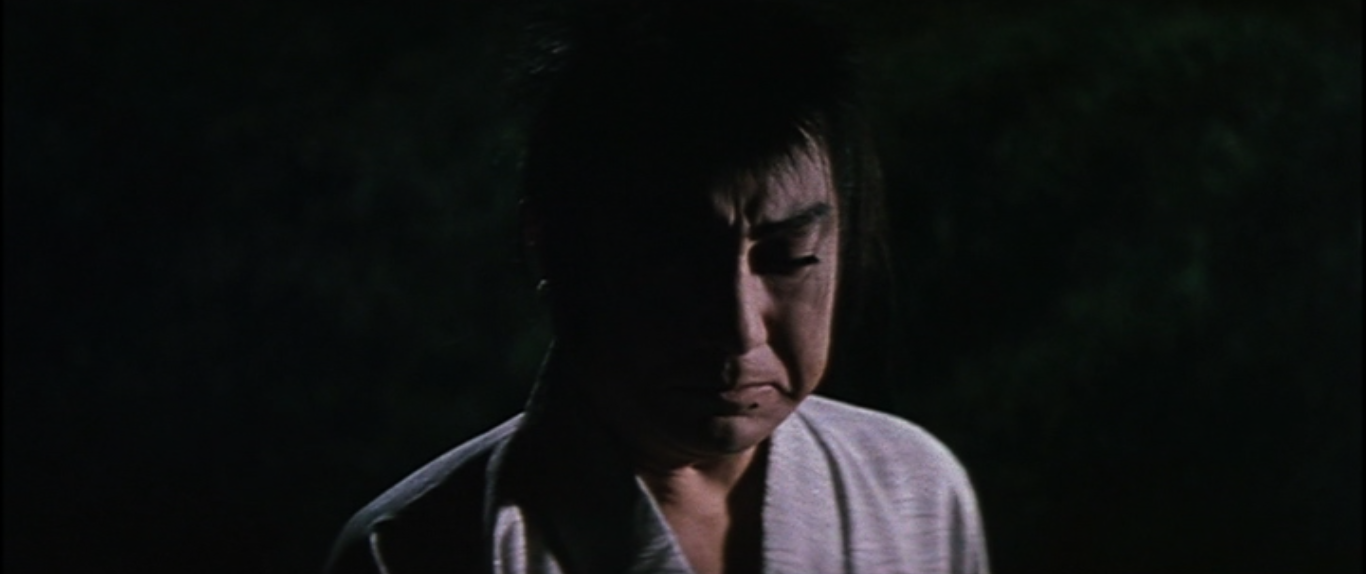

To fully grasp Kataoka Chiezō’s (and Uchida’s) interpretation of the protagonist, it’s instructive to compare his Ryūnosuke with the two other actors who have portrayed the role in the postwar era: Ichikawa Raizō and Nakadai Tatsuya. Ichikawa’s Ryūnosuke in the Satan’s Sword series is clearly a depressive; he’s utterly unresponsive to the people around him, except through violence. By contrast, Nakadai’s Ryūnosuke in The Sword of Doom is wildly, scarily manic, an out-of-control zombie killer. The very idea of this monster experiencing anything like remorse or guilt is ludicrous.

But if Ichikawa’s “hero” is depressive, and Nakadai’s is manic, Kataoka’s Ryūnosuke is clearly schizophrenic, a man utterly alienated from his own soul, haunted and burdened by his inability to feel ordinary human emotions. And like many such sufferers in real life, moments of lucidity, almost of “normality,” alternate with others in which his sickness takes full control.

The blogger who calls herself Paghat the Ratgirl has written (in her eccentrically-punctuated fashion) that she thinks Kataoka was overly conflicted about the character he played: “Nakadai with his Shakespearean training well understood the anti-hero through Hamlet or McBeth [sic], but Chiezō came out of the kabuki theater tradition wherein good was good & evil was evil & an evil hero was unthinkable.” Paghat’s point is that Kataoka, in her opinion, was temperamentally incapable of portraying the samurai as utterly bad, and therefore his performance suffered.

I would argue the opposite: I think the actor’s reluctance to depict his character as irredeemable lends his performance an ambiguity – and the film a capacity for suspense – that the other versions lack. When the samurai in Part II settles down with Otoku the medicine woman and her son, who resembles his own abandoned boy, it seems for a brief moment that the man might really change. He tells her sincerely that he loves his quiet life with her, and while playing with the child, he actually smiles. Ironically, Otoku herself brings about the end of this idyll when she implores him to intervene to stop the torture of the bridegroom from the Mochizuki clan by Lord Kamio’s men, and he reluctantly complies. (Uchida strongly implies that he does this just to get Otoku off his back.) But when he skewers, literally, a retainer, the need to kill is revived in him, and he abandons Otoku without remorse to pursue his bloody destiny – in Kamio’s employ.

The more often I see this film, the more Ryūnosuke’s logic for his actions makes a kind of crazy sense. His constant contention is that the sufferings of others – such as, for example, those of the Mochizuki clan – are their destiny, their karma, or else these are, as in Ohama’s case, the result of their own choices, for which he cannot and should not be held responsible. For example, he kills Ohama and later Kinzō purely in self-defense, and Otoyo’s tragic death was caused (from his point-of-view) by her freely choosing to assume responsibility for his welfare, so her friend Okimi (again, according to him) is wrong to expect him to mourn her.

Ryūnosuke’s unwillingness to take responsibility for his actions can at times be quite funny, as when the pro-imperial Tenshu fighters, at the end of their collective rope in their isolated hut, suggest mass suicide, and he lazily balks at their plan: they can kill themselves if they want, but he’s having none of it. His lack of any proper sense of giri (a samurai’s almost subconsciously ingrained sense of moral obligation) gives Uchida’s “hero” a curious freedom that may have been part of his appeal for the Japanese audience, tied as they have always been to their own unbreakable obligations. But this freedom is deceptive, because the samurai is ultimately enslaved by his mad need to kill. And his madness is a reflection in a distorted mirror of the everyday madness – the exploitation and violence – at the heart of the hierarchical society all around him.

The film is set in the so-called Bakumatsu (“end of the tent government”) era, shortly before the demise of the Tokugawa dynasty – which would also signal the end of the shogunate system and of the samurai class as a whole – a very popular setting for jidai-geki movies from the days of silent films to the present. The obvious explanation for the Japanese audience’s fascination with this period is that it was a time of great social turmoil and also of the troubled birth of the modern Japanese state, and therefore could easily be exploited dramatically.

However, there are surprisingly few signs of modernity in the trilogy. Some Western weapons, such as the hand grenade that Hyōma uses, appear, and we view Lord Komai’s incongruously European-looking house and possessions, but otherwise we could be in the Japan of almost any time during the Tokugawa era of the previous two centuries. But outward appearances aside, this was a decadent world, where people went through the motions of believing in values and carrying out customs that made less and less sense, and in which a sociopath like Ryūnosuke could easily thrive – a world much like our own.

One of the keys to understanding Uchida’s vision of the era is his fascinating depiction of the major female characters, because a very striking aspect of the protagonist is that he invariably attracts beautiful women – even when he can no longer even see them – like moths to the proverbial flame… sometimes literally, since two of the women, Ohama and her unrelated “twin” Otoyo, destroy themselves for his sake. His last woman, the neurotic and tormented Ogin, is also well on her way to ruining her life before Ryūnosuke himself self-destructs.7 Uchida takes the sufferings of these women seriously: they are tragic, not merely pathetic, heroines, and there’s a strong implication that they cling to this very odd man partly as their only security in a chaotic and rapidly changing social order.

The character of Ogin (very well-played by Kitagawa Chizuru, who portrayed the itinerant shamisen player in A Bloody Spear at Mount Fuji) is particularly intriguing. Her purple facial birthmark, which makes her unmarriageable, curiously foreshadows the similar “stain” of Sano Jirō, the doomed protagonist of Hero of the Red-Light District, released only one year after Part III of the trilogy. As in that later movie, Uchida explores the fascinating psychological phenomenon of “internalization”: the tendency of social pariahs to perversely embrace the shame of their outcast status.

One of the most poetic and saddest moments of the entire trilogy is when Ryūnosuke relates to Ogin his dream of two butterflies in combat (obviously symbolizing Ogin and the samurai himself), which can neither dominate one another nor leave each other alone.8 And the later scene in which the two lovers are attacked by Kamio’s men, and the samurai in a fit of frenzy kills them all, seems chillingly symbolic: the Revenge of the Monsters on the corrupt world that hates them. It’s one of the weirdest (and most weirdly theatrical) scenes in this very strange movie.9

(Continued on Page 3)