Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

(Continued from Page 2)

Hyōma is played by the young and very likable Nakamura Kinnosuke, who had started out in films only three years prior to the release of Part I. If Ryūnosuke can be considered the Macbeth figure in this story, Hyōma is the Hamlet figure, seeking not only vengeance but a way to make sense of his violent and chaotic world. Like Shakespeare’s character, he is obligated to kill by the rules of his social order, but also like the Danish prince, the meaning of his vendetta changes as the narrative progresses.

Unlike Ryūnosuke, who seems almost as immutable as granite, Hyōma grows and develops as he interacts with, and learns from, the people he encounters. From the anti-shogunate revolutionaries with whom he shares a jail cell, the young swordsman learns the value of patience. His love of the heroine, Omatsu, also humanizes him; though at first he puts his duty to avenge his brother above his desire to love her, in the end he struggles to find a way to accommodate both goals. And from the simple-hearted servant Yohachi he learns both humility and Buddhist precepts, which allow him to perceive his adversary not as a monster, but as a victim of his own sick compulsions.

The young man’s gradual maturation from callow swordsman, out for revenge simply because that’s what’s expected of him, to a mature man who feels empathy for his tormented enemy and wants to kill him chiefly to save his soul (and to put him out of his misery) is handled with surprising conviction by the actor, who would go on to a great run of films for Uchida. (See Notes on the Cast and Crew above.)

Buddhist philosophy completely pervades this film. According to Gregory Barrett, the distinguished critic Satō Tadao, citing Uchida’s autobiography, claimed that “Uchida was intrigued by the Buddhist elements in the original [novel] and likened its dominant tone to a Buddhist hymn (wasan).”1 Satō also theorized that Uchida’s memories of his experiences in China inspired the approach he brought to the trilogy. While residing in that war-and-revolution-scarred country, he recognized the truth of the Buddhist precept that life is suffering.2 This is why Uchida places so much more emphasis than, say, Okamoto did in his 1966 version on Ryūnosuke’s personal torment, and why Hyōma evolves from hating his enemy to pitying him.

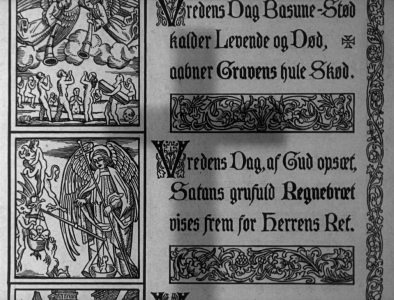

The Buddhist themes of this work can be detected even in the opening credits sequence. As the names of the crew and cast appear, the viewer sees a scroll in the background unwinding downward, starting from a scene showing saints or angels praying in heaven to a depiction of the full torments of hell. To those who’ve seen the Danish master Carl Theodore Dreyer’s 1943 classic, Day of Wrath (Vredens Dag), this imagery should seem very familiar, for in the opening moments of that earlier film (where the credits should be, though there are no credits), we also see a scroll that depicts the tortures of the Christian hell. Even the music on the soundtrack of both films is quite similar, so it seems to me undeniable that Uchida was directly alluding here to Dreyer’s masterpiece.

The most interesting aspect of this sequence is that Uchida has substituted Buddhist imagery for Christian symbols to evoke the same primal fear and dread. (It’s startling to me how easily the symbols of one religious tradition could be transposed into those of the other.) And in the final credits of the work, appearing at the end of Part III, the slow progress down the length of the scroll is reversed, and we travel upward from hell to heaven again – a possible allusion to Ryūnosuke’s reincarnation, as Dean Bowman has pointed out in his review.

I agree with Satō in his assertion that the film is ultimately more about the Buddhist concept of suffering than about evil. Although Ryūnosuke commits many sins in the course of the narrative, there’s one crime, shown near the end of Part III, which somehow seems more heinous than all the others: the murder of the servant girl. (Significantly, this act takes place near the old mill, the scene of his much earlier rape of Ohama.) His killing of the old man in the opening scene of Part I is indeed shocking, but that character was near the end of his life, whereas the young woman had her whole life ahead of her before her fatal encounter with the samurai.

Interestingly, she almost immediately realizes that Ryūnosuke is going to kill her, and even more interestingly, Uchida doesn’t focus on the face of the victim, which we barely glimpse, but on the utter savagery of the samurai’s expression as he runs his sword through her. In a Hollywood movie, the effect would be to make the viewer hate the protagonist, but because we have seen him in more benign contexts – saving Ogin from being raped by Kamio, for instance, or playing happily with the boy Kuratarō – the viewer finally perceives Ryūnosuke as Hyoma does: a man totally in thrall to homicidal impulses over which he has no control. We dread the character’s violence (from which he himself derives no pleasure), but also experience compassion for his madness.

It’s significant that Hyoma’s plan to revenge his brother by killing the samurai – the main engine of the trilogy’s plot – is never fulfilled. Even though Ryūnosuke is psychologically compelled to murder, he must atone for his crimes. But that atonement comes not in the form of the sword of an opponent, but of an overwhelming flood of unbearable emotions: it’s as if all his repressed grief and guilt is released at once.

The ending can be accused of sentimentality in its depiction of the samurai’s mad longing for his abandoned son. But Kataoka manages to pull off this difficult scene, howling like a wounded animal… or a damned soul. In the end, the most impressive achievement of the actor – and of the director – is to make the audience feel empathy (not sympathy) for the protagonist in spite of all the suffering his misdeeds have caused.

So far, I’ve spoken very little about the look of this film, but feel the need to comment on it, since it is with this work that Uchida inaugurated one of the main styles he would employ in his later films of the 1950s and 1960s. I call this the “Classical” style to distinguish it from the gritty, Realist style used in the silent Police Officer (and his later The Eleventh Hour) or the Mannerist approach seen in the final half-hour of Unending Advance (and also in the last half of The Mad Fox). The Classical style, used exclusively for movies set in the feudal era, takes full advantage of the latest widescreen and color film technology available to the filmmaker (christened by the studio “Toeiscope”) to create a world of dazzling images, while utilizing camera movements and close-ups discreetly, almost invisibly, in a very Hollywoodesque manner.

However, as Joe Walsh of the YouTube channel Nitrate Stock TV noted in an online review after watching Hero of the Red-Light District (in my opinion, the director’s finest work in the Classical style) at the 2016 MOMA Uchida Retrospective, “the color scheme was eye-popping, but muted at the same time.” In other words, the colors were exceptionally bright and vivid, yet never gaudy or tasteless. This approach fits Uchida’s purpose well in this series of works – which includes, in addition to the trilogy, Chikamatsu’s Love in Osaka, the aforementioned Hero of the Red-Light District, the Musashi series and the first half of The Mad Fox3 – because the attractive visuals are consistently used ironically by the director to suggest a pleasant surface that serves to conceal an ugly and rotten social reality… the nature of which I’ve attempted to evoke in the commentary above.

The style also serves another purpose: to distance the viewer, in almost Brechtian fashion, from the brutality she or he is witnessing. Ryūnosuke’s madness is consistently seen from the outside, often from the point-of-view of his women. This allows the viewer to judge the characters, and their era, more-or-less objectively.

It’s instructive to compare the trilogy with that other Uchida work about a serial killer: A Fugitive from the Past (Kiga Kaikyō, 1965). In that later movie, the Classical style would have been inappropriate; the narrative is set within the squalor of defeated postwar Japan, so there’s no glamorous surface reality to expose. Also, the killer Inugai (played, in a great performance, by Mikuni Rentarō) is perceived in that film largely from the inside, by using distorted visual imagery, via a technique called the “Toei-W106 Method” (Toei-W106 houshiki), to convey the protagonist’s unbalanced mental state. Thus, A Fugitive from the Past is both Uchida’s greatest Realist film and his greatest Mannerist movie – as well as the least Classical picture of his career.

I write at length on this matter to demonstrate that Uchida didn’t just put on or cast off a cinematic style as one would a suit of clothes, or to show off his technique, as some directors did (and still do); rather, he was extremely attentive as to how a particular style suited the vision he was trying to convey, and in this respect, the Sword in the Moonlight trilogy, though flawed in other ways, seems to me nearly entire successful.

Though heavy, illogically plotted, overlong and not a lot of fun, this trilogy, Uchida’s first long-form work of the postwar era, sustains an epic tone over all three installments, and the director – and the actor Kataoka Chiezō – make the film’s terrifying protagonist memorable.

Midnight Eye (Dean Bowman) (3/16/08)

Weird Wild Realm (Paghat the Ratgirl) (No date)

J.B. Spins (10/30/16) [review of MOMA Retrospective screening]

Japanonfilm (Anonymous reviewer) (11/08/18)

World Cinema Paradise (John David Baldwin) (12/12/16) [Includes my own, somewhat different, earlier take on the film]

I watched the entire trilogy last night. With his flat affect and sepulchral voice Chiezō Kataoka is pretty damned scary in this, especially in Part 1. I love how his ice-cold psychopathic killer consistently gets gorgeous women falling for him and taking care of him throughout all three movies, despite the fact that he has neither job nor money. (Ladies just love a nihilistic samurai, I guess.) The films’ sub-plots are not terribly interesting and render the whole thing somewhat unwieldy, but Ryūnosuke is a compelling character and you can see why he inspired multiple filmmakers to bring him to life. A very handsome Nakamura Kinnosuke is completely winning as Ryūnosuke’s youthful foe Hyōma. Overall too many jaw-dropping moments to mention here, but briefly I would like to cite the last scene in Part 2 as one of the coolest endings I have ever seen, in which reality suddenly collapses and we see Ryūnosuke in a dark and nebulous underworld (presumably his natural habitat). The astonishing sequence in Part 3 in which Ryūnosuke slowly emerges from a burning house at night and proceeds to lay waste to everyone in his path like the Angel of Death is all kinds of kickass.