Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

This page is for reviews of Uchida-related merchandise (books, DVDs, Blu-rays, etc.).

Reviews by the owner of this website and others of Uchida’s individual movies appear in separate posts appearing on the homepage, not on this page. Reviews of home media editions of Uchida’s films will focus primarily on the quality of the product (picture quality, supplements, etc.), rather than serving as reviews of the films themselves, so as not to unnecessarily duplicate the information and opinions included in the posts.

(For our review of the film itself, see here.)

It’s as rare as a snowstorm in April (or at least such freakish weather used to be rare) to see the release on home media in the U.S. of a film directed by Uchida Tomu. So, since I don’t wish to seem ungrateful to Arrow Academy for their release of this Blu-ray edition of a masterpiece film, I will keep whatever minor cavils I have brief, and restrict them to the beginning of our belated review of this 2018 release.

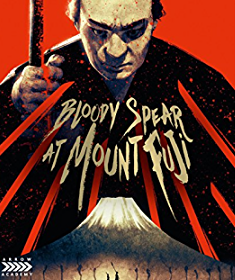

The cover art of the Blu-ray is very odd: not bad, exactly, just strange. The figure in the cover image towering over the famous mountain is obviously supposed to represent the spear carrier Gonpachi, the main character of the movie, played by Kataoka Chiezō. Yet the painted figure doesn’t look the least bit like that actor, who was a very major star in Japan at the time. Furthermore, in the printing of the film’s title a Gothic character font is used, which would be appropriate for a horror film but not for this one, and which makes the individual letters of the words appear to “drip” like blood.

Glimpsed below the mountain in the image are two tiny human figures in silhouette, obviously meant to represent the characters of Gonpachi and his fellow servant Genta, as they appear in the film’s very first scene, walking down the Tōkaidō Road in ancient Japan. But the third crucial figure in that opening scene, namely, Gonpachi’s and Genta’s beloved master, the samurai Kojūrō, is not represented at all, as if the two servants are traveling alone.

In short, the illustration simply doesn’t represent accurately the contents or mood of the film, which, its violent climax notwithstanding, is mostly a gently comic road movie about a samurai and two servants. The purchaser is given the option of reversing the cover sleeve so that the original Japanese poster art, featuring a photo of Kataoka himself, is visible instead. However, to be fair, that poster shows the star in a fierce pose, as if ready for war, which is, in a somewhat different way, also misleading.

But of course, few people buy a Blu-ray for its cover art. It’s the contents of the disk that matter and, in this case, those contents are splendid. The quality of the black-and-white print, given the film’s age (more than 65 years), seems to me superb. The supplements, which were taken from the original French DVD release on Wild Side Films (which is apparently no longer available from that company) are very informative and entertaining. And accompanying the film is an enlightening commentary track by Japanese film expert Jasper Sharp, which gives incredibly detailed information about most of the people involved in the making of the movie, some of whom operated very much behind the scenes but were nonetheless significant.

The highlight of the extras, for me, is a nearly hour-long interview from 2005 with Uchida’s son, Yusaku,1 who provides a wonderful sense of who his father was as a person and as an artist. He tells a very charming story about how, in the 1930s, Ichida and his family, including Yusaku, used to go to theaters that screened foreign films to watch Gary Cooper movies together, where the elder Uchida would feign annoyance at the love scenes. The son then movingly describes the deep friendship that developed between his father and the star Kataoka Chiezō during the making of Bloody Spear.

Perhaps most importantly, the younger Uchida gives an intriguing glimpse into the mindset that led his father to go to Manchuria only a few months before the end of the war, ostensibly to apologize for failing to make a planned film, and then to remain in China for over eight years. Yusaku points out that, at the end of the A Bloody Spear at Mount Fuji, Gonpachi continues alone on his journey carrying on his back boxes containing the ashes of his master Kojūrō and of his fellow servant Genta. This shot, as the man explains, would evoke for Japanese viewers the situation at the end of the Second World War, when soldiers and others often carried the ashes of the war dead on their backs to deliver them to the families of the deceased. He also points out that the musical score during this scene includes, anachronistically, the popular World War II propaganda hymn “Umi Yukaba” (“If I Go Away to Sea”). The son explains that these details signify that the elder Uchida had rejected the war he’d earlier supported, making the film a kind of “goodbye to all that” to Japanese militarism.

Another excellent interview subject is Toei employee Kishida Kazunori, who provides a brief but solid overview of the origins of the jidai-geki genre from the 1920s onward, and particularly of Kataoka Chiezō’s role in that development. We learn that Kataoka was very surprised when Uchida told him he wanted to stage a seven-minute-long fight scene with a spear during the climax of the film, because the scene as conceived differed so radically from the traditional swordplay he was so famous for. It’s implied that it was Kataoka’s respect for and trust in Uchida that made the scene work.

An interview with critic and film programmer Fabrice Arduini, titled “The Vagrant Filmmaker” (“Le cinéaste vagabond” in French) provides us with a very European take on Uchida’s achievement. Arduini’s central premise – that Uchida was a “nomad” whose creative restlessness led to the extraordinary variety of his cinema – is, in my opinion, basically accurate. Arduini, however, gives us some inaccuracies as well: he claims that Uchida’s postwar films were never entered into European film festivals, which isn’t the case – The Horse Boy (1957) competed at Berlin and The Mad Fox (1962) at Venice – and his interpretation of the mysterious “W106” code appearing within the Toei logo during the opening credits of A Fugitive from the Past seems to me entirely fanciful. But generally, Arduini’s information and interpretations are interesting and well presented.

If A Bloody Spear at Mount Fuji is viewed by itself, outside the context in which it was created, it would be easy, particularly for the non-Japanese viewer, to be misled by its mostly lighthearted tone. The package created for this Blu-ray release, which is essential for fans of Japanese Cinema, helps the viewer of the film understand not only why Uchida made the movie, but its serious critique of Japan’s feudal past – and its relevance to mid-20th Century Japanese history.