Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Other titles: Limitless advance (alternate English title); L’Avancée éternelle (alternate French title) Endless progress (literal English title)

| Production Company | Nikkatsu Tamagawa (Chōfu) |

| Scenarist | Yagi Yasutarō |

| Source | Ozu Yasujirō (original story) |

| Cinematographer | Midorikawa Michio |

| Music | Yamada Eiichi |

| Performers | Kosugi Isamu (Tokumaru, a middle-aged salaryman); Takihana Hisako (Tokumaru’s wife); Todoroki Yukiko (Fumiko, Tokumaru’s daughter, nicknamed “95 sen”); Egawa Ureo (Fumiko’s fiancé, Kita); Katayama Akihiko (Yuichi, Tokumaru’s son); Miake Bontarō (an office worker) |

| Status | Extant, but in heavily edited form (see below) |

| Photography | Black and white |

| Format | 35mm |

| Sound | Yes |

| English subtitles | Yes |

| Original Release Date | November 3, 1937 |

| Length | 99 minutes (original version); 74 minutes (current version) (see below) |

| Awards / Retrospective screenings | Kinema Junpo “Best One,” 1938; MOMA 2016 Retrospective |

Note: As far as I know, this film isn’t available on home video in any country. My only exposure to the movie was a single screening of the (presumably) only extant version at the 2016 Uchida retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. My memory of the work is therefore vague and may include errors or significant gaps. The synopsis below is the narrative of the film as originally released, as far as I can determine.

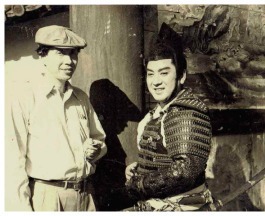

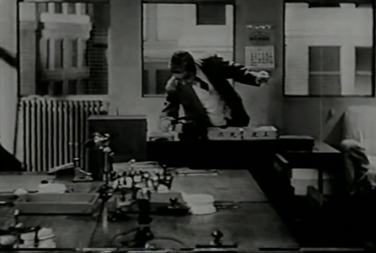

This post is illustrated by a surviving production still from the movie, as well as several screenshots derived from a brief clip from the film, included as part of an episode of the BBC documentary A Century of Cinema, entitled 100 Years of Japanese Cinema (Nihon eiga no hyaku nen, Nagisa Oshima, 1994). The screenshots appear here for educational purposes only under the Doctrine of Fair Use. It’s greatly to be hoped that a DVD and/or Blu-ray edition of the surviving version of this film, as imperfect as it is, will eventually be released.

Tokumaru is a hard-working and loyal salaryman for a large company who lives with his family in a suburb during the Depression. He has a wife, an adult daughter, Fumiko, with a poorly-paying job, and a young son, Yuichi. The daughter is engaged to an educated but unemployed man, Kita. The salaryman, who is in his mid-to-late fifties, is looking forward to his retirement at age 65, and in the meantime he is scrimping and saving to build his dream house, into which he plans to move with his wife after his working life is over. Tokumaru discusses the ongoing construction of the house with the contractor who, much to his chagrin, wants to charge him far above his original estimate, on the pretext that building costs are rising.

One day, he arrives at work and hears that the policy on retirement is about to be changed. With a co-worker approximately the same age as he, Tokumaru attends a company meeting in which the president announces that the mandatory retirement age has now been shifted downward from 65 to 55, and he and the co-worker will therefore be let go, effective immediately. This decision means that Tokumaru will never be able to complete his dream house, as he had been counting on the income he had expected to receive before reaching age 65.

While visiting the site of his half-constructed house, a thunderstorm breaks, and Tokumaru is knocked unconscious by a falling beam. He has a dream in which he has moved into the new house – which appears impossibly large and beautiful in the dream – where his son is taking piano lessons. His daughter is about to be married, and she thanks her father for the love and care he’s given her through the years.

When he awakens, the now mentally ill Tokumaru believes his dream to be real. The following day, he returns to the office in which he is no longer employed as though nothing bad had happened, and invites all his co-workers out to dinner to celebrate his “promotion.” The embarrassed company managers call Fumiko from the restaurant to take her sick father home. She arrives with her fiancé Kita, and the two horrified young people leave with the broken salaryman.

Todoroki Yukiko began her performing career as a very young teenager in the famed Takarazuka Revue acting troupe. In 1937, she suddenly switched to films: Unending Advance was her fourth movie that year. Her most famous role by far remains that of Sayo, the main female character in Kurosawa Akira’s celebrated debut, Sugata Sanshiro (1943), and she also appeared in the Kurosawa-directed sequel, Sugata Sanshiro II (Zoku Sugata Sanshiro, 1945). After the war, she continued in films as a prolific character actress, often appearing in works by Kawashima Yūzō, including his classic Suzaki Paradise: Red Light (Suzaki paradaisu akashingō, 1956), the director’s favorite of his films. She also acted onstage. She died in 1967 at age 49.

Egawa Ureo was a Japanese actor of mixed German-Japanese descent. While Egawa was still in his teens, he started his acting career at Taikatsu Studio in 1920, at about the same time as Uchida. However, he soon became a notorious delinquent; the novelist Satomi Ton modeled the protagonist of his novel, Juvenile Delinquent, after him. Once he had passed through that phase, however, he enjoyed a busy prewar career, acting in films by Ozu – Where Now Are the Dreams of Youth (Seishun no yume ima izuko, 1932) and Woman of Tokyo (Tōkyō no onna, 1933) – Shimizu Hiroshi – Japanese Girls at the Harbor (Minato no nihonmusume, 1933) – and Gosho Heinosuke – The Bride Talks in Her Sleep (Hanayome no negoto, 1933). In the postwar era, he appeared in, among many other films, Ozu’s Equinox Flower (Higanbana, 1958) and the Hollywood-produced movie Escapade in Japan (Arthur Lubin, 1957). For Uchida, his final performance was in a minor role in Twilight Saloon (Tasogare Sakaba, 1955). His last role before his death in 1970 was as a benign scientist in the 1966 television series Ultra Q, the first in the popular “Ultra” cycle of Japanese TV series.

Midorikawa Michio, Uchida Tomu’s brother-in-law – his younger sister was the director’s wife, Yoshiko – served as cinematographer on this and at least three other Uchida projects, including the classic Earth (Tsuchi, 1939) and a two-part period film set during the Boshin War, History (Rekichi, 1940), now lost. He also worked for such prominent directors as Abe Yutaka, Nomura Hōtei and Shimazu Yasujirō. One of the latter’s early films lensed by Midorikawa, Father (Otōsan, 1923), was the very first of Shochiku Studio’s shomin-geki films about the daily lives of ordinary working people, a genre that remained popular for many decades. Although his credits as cameraman abruptly end during the prewar era with Uchida’s History, he served as technical advisor on the director’s A Fugitive from the Past (Kiga Kaikyō, 1965). In 1987, he published a memoir, Cameraman’s Movie (Kameraman no eigashi: Midorikawa Michio no ayunda michi), and he long outlived his famous relative, dying in 1998 at age 95.

Although a number of films directed by Uchida that were released prior to the mid-1930s had earned respectful reviews, and presumably some box-office success, it was in the 1936-1937 period, after his return to Nikkatsu from his brief stint as a director at Shinko Studios, that he finally emerged as one of the most important Japanese directors, the artistic and commercial peer of Ozu, Mizoguchi, Naruse Mikio, Gosho Heinosuke and Yamanaka Sadao. (The latter would soon be drafted into the army and sent to China, where he would die at age 28.) In 1936, Uchida had released Theater of Life: Youth Version, the first installment of a two-part adaptation of Ozaki Shiro’s popular novel, with Kosugi Isamu as the embittered Meiji-era protagonist.1 The movie appeared in second place in that year’s Kinema Junpo (KJ) critics’ poll: the filmmaker’s highest placement in the poll yet.

In the following year, 1937, Nikkatsu released Uchida’s The Naked Town (Hadaka no machi), starring both Kosugi and Shima Kōji, which attracted favorable attention for both political and artistic reasons. (The film is now lost.) As a literary adaptation, it had somehow escaped the bonds of censorship despite its allegedly harsh portrayal of urban poverty. And some critics and composers were very impressed by the fact that the music in the movie was, as today’s scholars would say, “diagetic”: that is, all of the music came from a source in the world of the film and was heard by the characters as well as the audience.2 (Uchida would later do something very similar in the semi-musical Twilight Saloon (Tasogare sakaba, 1955).) This movie appeared in fifth place in that year’s KJ poll.

But The Naked Town was overshadowed by another 1937 Uchida release: Unending Advance, his fourth consecutive literary adaptation and the first of two Uchida films in three years (the second one was Earth (Tsuchi)) to top the KJ poll. The ultimate origin of this work was a published story by, of all people, Ozu Yasujirō. As Ozu-san, a website about the filmmaker’s life and career, relates: “After the completion of The Only Son [Hitori musuko, 1936], Ozu planned to make a film with the title What a Cheerful Guy, This is Mr. Yasukichi (Tanoshiki kana Yasukichi-kun). However, Ozu abandoned this story of an old office worker who becomes insane, because there were objections to making it after the dark and hopeless The Only Son.”

The objections almost surely came from Kido Shirō, the head of Ozu’s studio, Shochiku, who preferred his movies upbeat and uplifting, and would never have greenlighted such a grim and suspiciously Left-wing-sounding story, particularly after the only slightly less downbeat The Only Son.3 But Nikkatsu’s top brass had no such qualms, and they purchased the rights to the story, which Uchida and his screenwriter, Yagi Yasutarō, then adapted, employing a different but equally ironic title. The result is a movie as unlike the work of Ozu as can be imagined: angry, tragic, at times surreal… and anything but accepting of “life as it is,” as Ozu’s films are legendary for being, or seeming to be.

In the opening scenes of the film, the director appears to mimic the work of another director named Yasujirō: namely, Shimazu Yasujirō, the originator of the shomin-geki genre of films about ordinary life among the lower and middle classes. Uchida’s cameraman, Midorikawa Michio – see Notes on the Cast and Crew above – had been present at the creation of that popular genre. Right after the Great Kantō earthquake, Midorikawa had shot for Shimazu, the only director left at Shochiku’s Kamata (Tokyo) studio after the quake, the movie Father (Otōsan, a.k.a., Chichi, 1923).

Father was a comedy about the relationship of a star baseball player and his father, which, according to Anderson and Richie, “relied more on character and mood than upon plot and slapstick.”4 It followed Kido’s new strategy of filming stories about ordinary Japanese men and women, rather than plots derived from Kabuki or Shinpa melodramas. As Kido himself described his thinking years later “I wanted to take some of the material that was all around us… in other words, use real material. That was the beginning of the Kamata style.”5 Specifically, Uchida’s film seems to me to echo Shimazu’s Our Neighbor, Miss Yae (Tonari no Yae-chan, 1934), the charming slice-of-life film about modern young people that that director had made just three years earlier.

But from the first scene, the tone of Uchida’s film is subtly different from Shimazu’s gentle observational comedy: it uses “the material that was all around us” in a totally different way. The film begins with a lighthearted situation that could easily have been found in a Hollywood comedy of the time, depicting a young man cheerfully playing children’s games with the neighborhood kids – but the real reason he’s acting so childlike is because he’s got no job. The little boys have gleefully nicknamed his fiancée, Fumiko, who does have a job, “95 sen,” because that amount of money – that is, just under one yen – constitutes her entire daily wage: a paltry sum, even for Depression-era Japan. By the time the dedicated salaryman Tokumaru, Fumiko’s father, arrives home after a hard day’s work, the absurdity and desperation of the economic situation in mid-1930s Japan (the world outside the movie theater) has been brought home to the audience.

The heart of the film, in its second half, is a dream sequence – actually, a hallucination, as Tokumaru has been knocked unconscious – in which the now-unemployed man imagines he has magically attained everything he had wished for himself and his family. But even in the narrative’s first half, we can see that his hopes for a better life, under these grim circumstances, are themselves a kind of hallucination. His lofty plans for building an expensive dream house are brought down to earth by the greed of the contractor, who insists on charging the salaryman far more than the original estimate, citing the steeply rising costs of building materials (though he may not be lying about these costs).

The scene in which Tokumaru arrives for work in the morning also seems dreamlike. He greets a co-worker and proceeds to his desk, where he takes out a large handkerchief, unfolds it, lays it on the desk and then fastidiously removes and folds his suit jacket, ties it with the handkerchief and stows it away in the desk. Tokumaru performs this routine as if sleepwalking, and in a sense he is: he’s using habitual gestures and boring routine to lull himself into a false sense of security. (It’s difficult to believe that only two years later, Kosugi Isamu, who plays this fastidious middle-class man, would portray the brutish and filthy peasant Kanji in Uchida’s greatest prewar masterpiece, Earth.)

When the management at Tokumaru’s company announces that the retirement age has just been retroactively shifted downward from 65 to 55 – a milestone the unlucky Tokumaru has already passed, putting his dream house, with all his other hopes, completely beyond his financial reach – Uchida’s depiction of this scene seems very contemporary in its comic awfulness. The speech the company president gives announcing the policy change is full of smug, lachrymose hypocrisy. He even speaks of firing the older workers through his tears, as though he, not the dismissed men, is the victim, even though management is obviously letting its “retired” workers go solely to maximize profits. (I can attest that this two-faced attitude is alive and well in present-day corporate America; one could easily remake this movie with a contemporary American setting with only superficial changes.) A colleague of Tokumaru’s has also been forcibly retired, and the two men, beyond the humiliation of their dismissal, must endure together this insultingly condescending speech.

When the defeated Tokumaru visits the site of his never-to-be-completed house during a thunderstorm and is knocked out, the dream sequence begins. This may be the most charming set piece in all of Uchida’s surviving films. As Alexander Jacoby notes, “With its stylised visuals, settings and acting, the dream seems almost a satire on Hollywood cosmetics and wish fulfillment.” It represents the first use of which I’m aware of the quasi-surrealistic style that Uchida would later explore in more depth in The Mad Fox (Koiya koi nasuna koi, 1962) and A Fugitive from the Past.

Also impressive within this fantasy sequence is the scene depicting the family’s hiking trip in the countryside, which greatly impressed me when I saw the film. Though I only vaguely recall the details now, it suggested to me at the time the unreal world of Hollywood musicals. The daughter Fumiko even sang as she strode briskly over mountain roads. The tone was ironic, and everything about the visual style suggested a kind of parody. Yet the love the family members shared during the salaryman’s imagined holiday was obviously real, giving weight to the narrative’s subsequent tragic events.

There is throughout the dream an obvious undertone of bitterness, as Uchida never lets us forget that this delightful vision of an office worker’s bourgeois fantasy of heaven-on-earth (probably inspired by the similar comic dream in Chaplin’s The Kid) is the opposite of reality, and the viewer feels increasing suspense about what the betrayed salaryman will do when he finally wakes up. But in a sense, Tokumaru never does wake up: in his madness, he remains in the dream forever. And therein begins the story within a story: the tale of how the film, like its protagonist, was broken beyond repair by indifferent corporate forces.

(Continued on page 2)

[…] Unending Advance (Kagirinaki zenshin, 限りなき前進), 1937 […]

[…] film presents an innocent world to which Uchida would never return, except in the dream sequence in Unending Advance. Nearly all the characters, even the milkman, are scrupulously honest and kind. Only the […]

[…] as Theater of Life: Youth Version (Jinsei gekijo: Seishun hen, 1936, which I haven’t yet seen), Unending Advance (Kagirinaki zenshin, 1938), and Earth (Tsuchi, 1939). (Locating a complete version of any of these […]

[…] six of Uchida’s prewar films, including as the middle-aged wife of the tragic protagonist of Unending Advance (Kagirinaki zenshin, 1938), despite the fact that she was only about 30 at that time. In the […]

[…] Unending Advance (Kagirinaki zenshin, 限りなき前進), 1937 […]

[…] became more pronounced with age. His versatility is impressive in such Uchida films as this one, Unending Advance (1937) and Earth (1939). He’s perhaps best known for his leading role in the infamous […]