Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

(Continued from page 1)

Fast-forward to the immediate postwar era. As the Japanese Wikipedia article about the film relates the story, Uchida is still in China, and Nikkatsu, his former company, is wondering what to do about the Uchida films in its vaults during his absence – specifically, if and how it should re-release them. Unending Advance must have seemed the most tempting candidate for a reboot. After all, except for Earth, the 1937 film was the most acclaimed work of Uchida’s entire prewar career, and no print of Earth existed at that time in Japan.1

As the director was not around to object, the studio made substantial cuts to Unending Advance. The censorship office at Allied Headquarters, known as GHQ, which reviewed all released and re-released movies at that time, passed this new version, and so the studio released the movie for the second time.

Uchida returned to Japan in October 1953. Somewhere along the line, he was informed of the fate of Unending Advance, viewed the edited film and was appalled. He apparently combed Nikkatsu’s archives for the original negative or prints, or for the footage Nikkatsu had edited out of the print, all to no avail: the cut footage had apparently been discarded or destroyed, so that only the mutilated film remained. The dispute between filmmaker and studio involved the very point and purpose of the film. Nikkatsu had changed Uchida’s tragic ending to a happy one, by editing the film in such a way that the deliberately absurd dream sequence was presented as the real-life resolution of Tokumaru’s troubles.

This comic conclusion to a sad story has been misleadingly compared to the deliberately unreal happy ending of Murnau’s masterpiece The Last Laugh (Der letzte Mann, 1924), in which the demoted and defeated protagonist is, at the end, suddenly elevated to the upper classes when he inherits a fortune. The big difference between the two works is that Murnau had deliberately planned that tonally “false” ending – the frequent claim that it was forced upon him by his studio is without foundation – whereas the nonsensical ending of Unending Advance was imposed upon the film by Nikkatsu without its creator’s knowledge or consent.

The impasse was ultimately resolved in favor of the director. Nikkatsu agreed to re-edit, or allow Uchida to re-edit, the sole existing print, placing title cards at strategic points in the last third of the film to explain to the audience that the dream sequence is indeed a dream, and that Tokumaru is in fact insane when he takes his office colleagues out to dinner the following day. Only part of one brief scene from the original ending survives, in which the mad Tokumaru entertains his colleagues at dinner by singing an old folk song. Other title cards explained that Fumiko, summoned by the embarrassed managers of the company, arrives at the restaurant with her boyfriend Kita to take her sick father home.2

A very odd version of this climactic scene as it appears in Yagi’s original script has been preserved. According to Yamamoto Naoki in the book Dialectics Without Synthesis, the screenwriter’s version was different from both Ozu’s original story and from the final version of the film Uchida edited. In Ozu’s story, the salaryman is only pretending to be insane, Hamlet-like, in order to note the effects of his behavior on his family and associates.3 In Yagi’s script, however, the protagonist’s madness is real and, according to Peter High in his classic book The Imperial Screen, the young couple is appalled by the spectacle of the father’s behavior, as the fiancé demands that the company be held responsible. Then he launches into what Prof. High calls an “eerie and unconnected peroration” containing “the lurking spirit of Nazism”:4

It’s a plain fact that if you want to fight, you’re going to have to fight spiritually and economically, just to survive in the everyday world. It’s open warfare: between individuals, states, races; there’s even a conflict pitting one generation against another! Every battle has its own characteristics, but basically they are all the same – they amount to the struggle for survival… In this survival-of-the-fittest world, look where father’s gotten himself. He tried to take on the world with his honesty and negative life force. Now’s the era of positive life force. Fight for life with the utmost fury, seize by violence the opportunity to live! The more brutal the struggle for survival, the deeper the appreciation for the fragility of physical existence.

Ibid.

It should be noted that this quasi-Hitlerian speech, in addition to being totally out-of-character in the mouth of this otherwise easygoing young man, is a typically grotesque right-wing distortion of Darwinian science. A very defensive Yagi in 1966 confessed that his script “… involved the ideological confusion and anxieties of the World War II years [in fact, the war didn’t even begin until nearly two years after the movie came out]… It was a script deeply influenced by my mental confusion at the time.”5 In other words, the Fog of War was to blame.

At the last minute, though, Uchida, after filming the speech described above, decided to edit it out of the finished film, substituting a sad final shot in which the trio – the ill father, the daughter and the fiancé – walk across a bridge at dusk as vehicles and people pass by indifferently. Contemporary reviewers who took note of the different versions of the ending mostly approved of Uchida’s decision to cut the speech.6 Uchida could have left the speech in the film to curry favor with the militarist government, but the better part of the director’s nature prevailed.

So what we have left in the end is, perhaps, a ruined masterpiece. By comparison, the director of The Magnificent Ambersons might well have considered himself lucky.

In an important moment within the dream sequence, Tokumaru’s daughter Fumiko appears in a traditional Japanese wedding costume, as she’s about to be married. Very movingly, Fumiko kneels and thanks her father for the love and care he’s given her all her life. The scene is particularly noteworthy because it was echoed twelve years later in the climactic scene of Ozu’s postwar masterpiece Late Spring (Banshun), in which Hara Setsuko plays the marrying daughter, who gives thanks (in reality this time, not a dream) to her father, played by Ryū Chishū, in almost exactly the same way.

Because the resemblance of the two scenes can’t be a coincidence, and since Unending Advance was derived, as already mentioned, from an Ozu short story, the question for the film scholar would clearly be: did Ozu in the postwar era “borrow” from himself, or from Uchida (and Yagi)? I’ve never read the Ozu story from which the 1937 movie was derived, so I’ve no idea whether the bride’s farewell speech is his invention or that of the filmmakers. But if the latter is true, this would be a very pleasing example of what I call “cross influence” among film artists – and also a typical example of how Japanese filmmakers have swiped Uchida’s ideas without crediting him.7

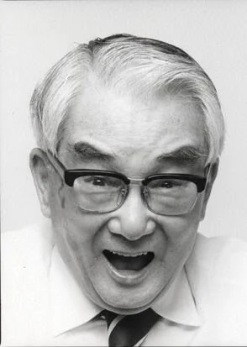

Another indication of the fact that Japanese filmmakers didn’t forget this movie and the impact it made on them can be found in a personal list of his favorite films of all time by Kurosawa Akira, compiled near the end of his life. (Since he limits himself to only one film per director, this actually functions more as a “best directors” list than a “best films” list.) For the year 1939, Kurosawa chose Uchida’s Earth, and added the following comment: “Of course [Uchida’s] ‘big’ [postwar] movies are not bad, but I personally like his earlier works more, for example Kagirinaki zenshin. But, very unfortunately, almost none of his [prewar] films are in existence anymore.”

The implication would seem to be that if Earth didn’t exist, he would have selected this slightly earlier work instead. Kurosawa doesn’t explain in his comments why either of these films appealed to him, but their presence in his list and in his memory isn’t surprising, given Uchida’s great prominence in the film world at a time when the younger man, then still working as an assistant director, was trying to find his footing in that world.

Although this may or may not have been intended as political commentary, the title “Unending Advance” (which can also be translated as “Endless Progress”) could be interpreted as a parody of the “unending advance” of the Japanese Imperial Armed Forces throughout China, and subsequently much of the rest of Asia, which was loudly celebrated by the military government almost to the end of the war. Therefore, Tokumaru’s “advance” towards madness and self-destruction might be seen as an ironic foreshadowing of the Japanese Empire’s advance toward its own destruction, as asserted in the narration of the TV documentary100 Years of Japanese Cinema, by Oshima Nagisa (Channel 4 (UK), 1995), in which an extended clip of the film is shown.

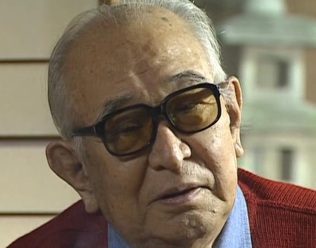

Japanese Wikipedia attributes the high reputation of Uchida’s film among younger audiences in the 1970s as being largely due to the influence of broadcast journalist Yodogawa Nagaharu, who hosted the TV program Sunday Movie Theater (literally, “Sunday Western Painting Theater,” Nichiyō yōga gekijō) for 36 years, from 1962 to shortly before his death in 1998. Yodogawa was a fervent champion of Unending Advance, and he’d obviously seen it during its original release (he was born in 1909), as his evocation of the work for his audience (again, according to the Japanese Wikipedia article linked above) included a detailed description of the now-missing ending.

By all accounts, Yodogawa was a passionate enthusiast for cinema from the silent era onward, and his enthusiasm was contagious. He knew how to communicate to a mass audience without falling back on the lingo of film theory, and his passion made him a popular, even beloved, personality. And it has occurred to me while reading about him that there’s never been any American equivalent to such a public figure. We have broadcast reviewers and critics, yes, but no one so extraordinarily knowledgeable about cinema’s history who similarly advocates for film as an art form. It seems to me that artists like Uchida require champions like Yodogawa, and perhaps the reason that there are so few filmmakers today comparable to Uchida is the absence, in today’s world, of the Yodogawas – a lack I have no idea how to remedy.

Although horribly mutilated by the studio, the surviving fragment of Uchida’s ambitious work brilliantly combines his mastery of realistic detail with his genius for exuberant, surreal fantasy.

Museum of Modern Art Uchida Film Festival [2016 MOMA Retrospective]

Senses of Cinema (brief discussion of the film) [Alexander Jacoby]

What Did the Lady Forget? (brief discussion of Uchida’s film in the context of Ozu’s 1937 film) [Ozu-san website]

[…] Unending Advance (Kagirinaki zenshin, 限りなき前進), 1937 […]

[…] film presents an innocent world to which Uchida would never return, except in the dream sequence in Unending Advance. Nearly all the characters, even the milkman, are scrupulously honest and kind. Only the […]

[…] as Theater of Life: Youth Version (Jinsei gekijo: Seishun hen, 1936, which I haven’t yet seen), Unending Advance (Kagirinaki zenshin, 1938), and Earth (Tsuchi, 1939). (Locating a complete version of any of these […]

[…] six of Uchida’s prewar films, including as the middle-aged wife of the tragic protagonist of Unending Advance (Kagirinaki zenshin, 1938), despite the fact that she was only about 30 at that time. In the […]

[…] Unending Advance (Kagirinaki zenshin, 限りなき前進), 1937 […]

[…] became more pronounced with age. His versatility is impressive in such Uchida films as this one, Unending Advance (1937) and Earth (1939). He’s perhaps best known for his leading role in the infamous […]